The world's biggest experiment is back on track

Some 400 days after a poorly soldered join gave way, the biggest and most complicated scientific experiment ever built, is finally ready to go again.

Some 400 days after a poorly soldered join gave way, the biggest and most complicated scientific experiment ever built, is finally ready to go again.

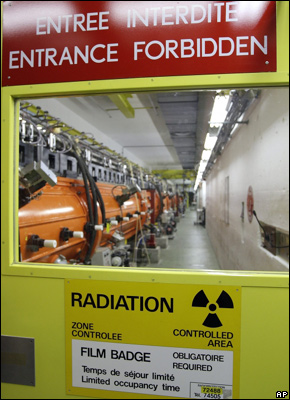

Some time in the next few days the Large Hadron Collider - the giant atom smashing machine buried beneath the alps on the Swiss-French border near Geneva - will be fired up again. Streams of protons travelling at close to the speed of light will hurtle both ways around the 27 kilometre ring that makes up the bulk of the machine.

Amid much fanfare the LHC flickered briefly into life in September 2008. But just nine days later that join - one of 24,000 - shorted out, triggering a dramatic rise in temperature and a sudden release of liquid helium.

The scientists at CERN don't like to talk about an explosion - operations group manager Steve Myers refers to "strong forces" being brought to bear - but in all more that 37 of the giant dipole and quadrupole magnets, each weighing several tonnes and connected together in sequence like the carriages of a train, were shunted out of position. It must have been quite a bang.

Part of the reason why it's taken so long to get the LHC back on track has been the need to ensure nothing like that could possibly happen again.

As Paul Collier explained to me down in the LHC tunnel, the problem with any superconducting machine is that it has to operate at such low temperatures to reduce resistance (the LHC operates at minus 271 degrees).

"When you cool down everything gets shorter. So one of the problems with any superconducting machine is electrical problems, things that only appear when components shrink or change dimension so dramatically. Then you can have wires that suddenly touch or snap."

"When you cool down everything gets shorter. So one of the problems with any superconducting machine is electrical problems, things that only appear when components shrink or change dimension so dramatically. Then you can have wires that suddenly touch or snap."

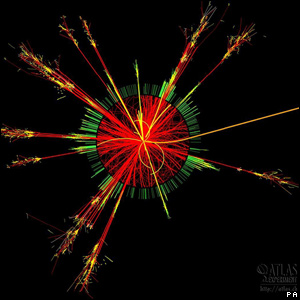

But getting the LHC up and running again is only a first step. The real work - the new science - will be done by the giant experimental detectors that straddle the ring at the points where the proton beams cross.

The energy released in these collisions will re-create the conditions that existed a split second after the big bang itself, giving us vital insights into the nature of the material world, revealing the secrets of dark matter, and even pointing the way to a theory of everything.

In order to see this content you need to have both Javascript enabled and Flash installed. Visit BBC Webwise for full instructions. If you're reading via RSS, you'll need to visit the blog to access this content.

Professor Jim Virdee, the lead scientist on the CMS detector - the biggest of the four main experiments at CERN - admits to a degree of frustration at the delay. Now, at last, he's ready to get going again.

"We're incredibly keen, incredibly excited again. In a sense we're half way there. The construction is finished now and the extraction of new science is about to begin. Some incredible discoveries are ahead of us".

I'm Tom Feilden and I'm the science correspondent on the Today programme. This is where we can talk about the scientific issues we're covering on the programme.

I'm Tom Feilden and I'm the science correspondent on the Today programme. This is where we can talk about the scientific issues we're covering on the programme.

Comment number 1.

At 15:15 17th Nov 2009, malcolm mcewen wrote:as one of the fringe element who believe the LHC constitutes a grave risk to all of humanity I do not look forward to imminent restart of this the most expensive and redundant machines ever built. Redundant? well even if I and the others who share my concerns are wrong and the scientists at CERN are correct and they achieve their objective the benefit to humanity will be equal to the benefit of not using it... we gain nothing, the standard model is corroborated, science proves what it theoretically suspects but in terms of practical benefit there are none.

However what has particularly interested me since the spectacular failure last year has been the response of CERN, in particular the need to replace all the solder joints. Surely one failure is acceptable but the idea that all the joints were faulty should have raised eyebrows but very little has been reported and nothing has been said about what the joints were replaced with. Why you may ask is this significant?

Well solder is primarily made of lead and the protons used in collisions at CERN are from lead nuclei. I suspect that the joint itself didn’t fail but the matter it was made from did!

If you’re a good journalist then do some digging and if as I suspect you find that CERN replaced the old lead solder joints for a lead free solder then dig some more. For we are very soon in for a major major change in our reality.

Complain about this comment (Comment number 1)