How far should scientists take animal research?

From Frankenstein to the Island of Dr Moreau we're well used to the idea of scientists (mad or otherwise) pushing the boundaries of what is, and is not, acceptable.

From Frankenstein to the Island of Dr Moreau we're well used to the idea of scientists (mad or otherwise) pushing the boundaries of what is, and is not, acceptable.

After all, revolutionary breakthroughs are rarely found in the comfy middle ground, but rather at the cutting edge of what's not yet possible.

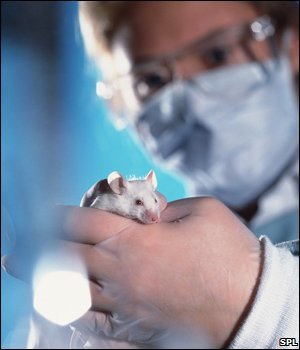

So it comes as something of a surprise to find a group of scientists inviting the public to tell them how far they should go with a controversial area of research. But that's exactly what the Academy of Medical Sciences is doing today. It's launched a new study into the use of animals containing human genetic material in medical research.

The work, which involves genetically engineering animals (typically mice) to include human genes associated with specific disorders, allows researchers to study human diseases in animal models in the laboratory.

In research aiming to treat a blood disorder for instance, that might involve knocking out the gene that codes for haemoglobin in a mouse, and replacing it with the human version of the same gene. That way, researchers are able to study the impact of any new technique or treatment on human, rather than mouse proteins.

It's an area of medical research that has proved incredibly successful over the past 40 years, making a huge contribution to our understanding of disease processes, and helping to develop treatments and cures for a wide range of genetic disorders.

But as the power and sophistication of the techniques has developed, so it has become possible to do more and more.

While it might be acceptable to transfer an entire human chromosome into mice to study a chronic degenerative disorder like Multiple Sclerosis, would we feel the same about a rat with an equivalent proportion of human neural material - brain cells - in its genetic make up? Would we be comfortable adding human brain function to another primate? Or how about the genes associated with speech?

These are the sorts of question professor Martin Bobrow, who will chair the AMS working group, says the public have a right to decide.

In order to see this content you need to have both Javascript enabled and Flash installed. Visit BBC Webwise for full instructions. If you're reading via RSS, you'll need to visit the blog to access this content.

"Some of these developments challenge our idea of what it is to be human. It is important to ensure that this exciting research can progress within limits that scientists, the government, and the public support."

Certainly it would challenge attitudes to research on animals profoundly, if the macaque in the cage was heard to wish the researcher a "good morning" as he came into the lab each day.

I'm Tom Feilden and I'm the science correspondent on the Today programme. This is where we can talk about the scientific issues we're covering on the programme.

I'm Tom Feilden and I'm the science correspondent on the Today programme. This is where we can talk about the scientific issues we're covering on the programme.

Comment number 1.

At 17:44 11th Nov 2009, jr4412 wrote:Tom Feilden.

"These are the sorts of question professor Martin Bobrow, who will chair the AMS working group, says the public have a right to decide."

given that the public are mostly 'educated' through the media, that is a daunting prospect.

for instance, the current controversy surrounding the the Home Secretary's dismissal of Professor Nutt: the politicians do not accept rational scientific advice and the public is (if anything) apathetic; the media deliberately misinform (for instance, the BBC does not even include alcohol and tobacco in its Drugs: the facts advice) and Professor Bobrow thinks that important decisions should be left to the people -- who aren't given (allowed?) access to all of the relevant information, even if they could appreciate all of the implications.

sounds like a recipe for (even greater) disaster!

Complain about this comment (Comment number 1)