Celebrating 350 years of scientific achievement

"Nullius in Verba" - which loosely translates as "take nobody's word for it" - seems to sum up the dramatic departure the Royal Society's foundation represents from the classical Greek tradition of scientific inquiry.

"Nullius in Verba" - which loosely translates as "take nobody's word for it" - seems to sum up the dramatic departure the Royal Society's foundation represents from the classical Greek tradition of scientific inquiry.

Emerging from what one of its founders, the chemist Robert Boyle, described as an "invisible college" of 17th century natural philosophers, who met first in Oxford and later in London to discuss the ideas of Francis Bacon, the Royal Society was officially constituted at Gresham College in November 1660.

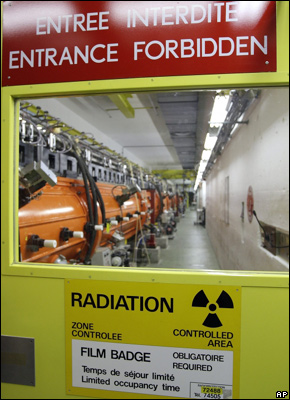

But what was different about the Royal was its emphasis on the application of science for the benefit of mankind, and crucially on the use of observation, measurement and experimentation.

As the Sussex University astronomer and author of The Fellowship: A History of the Royal Society Dr John Gribbin says, the key change was the idea that the universe is governed by laws that we can understand here on earth.

"This is the idea that came to be known as the clockwork universe. That the universe runs on physical laws that we can understand, and apply equally on the surface of the Moon and Mars, and not by the capricious whim of the Gods".

In order to see this content you need to have both Javascript enabled and Flash installed. Visit BBC Webwise for full instructions. If you're reading via RSS, you'll need to visit the blog to access this content.

To mark this historic milestone the Society is launching a new website featuring 60 of the most exciting, influential and inspiring inventions and discoveries that have been published in its journal (see the audio slideshow) - itself the oldest peer review scientific journal still in continuous publication - Philosophical Transactions.

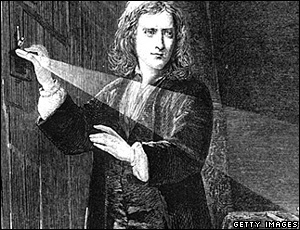

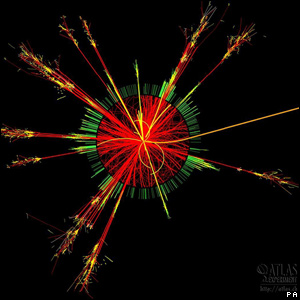

Highlights include an account of Daines Barrington's examination of an eight year old Mozart (to establish whether he really was a child genius), Isaac Newton's landmark paper on the refraction of light, Crick and Watson's description of the structure of DNA, and Stephen Hawking's ground breaking early work with Roger Penrose on the structure of black holes.

Enjoy.

I'm Tom Feilden and I'm the science correspondent on the Today programme. This is where we can talk about the scientific issues we're covering on the programme.

I'm Tom Feilden and I'm the science correspondent on the Today programme. This is where we can talk about the scientific issues we're covering on the programme.