Can machines think?

What is the measure of intelligence? And can an inanimate machine - however sophisticated - ever be said to be thinking for itself?

What is the measure of intelligence? And can an inanimate machine - however sophisticated - ever be said to be thinking for itself?

It's a question that has preoccupied computer scientists - and inspired science fiction writers - in equal measure.

But it wasn't until 1950 that we even had a definition of what constitutes independent thought by a machine. That was when Alan Turing, the father of modern computing who helped to break the enigma code at Bletchley Park during World War II, came up with a "test" to assess whether a computer was thinking for itself.

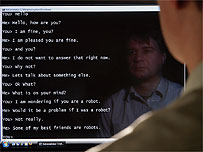

In the Turing Test a machine seeks to fool a group of judges into thinking they're holding a text based conversation with a person in another room. The idea is that if, after a five minute conversation and asking anything you like, you still can't tell you're talking to a machine then (to all intents and purposes) it can be said to be thinking for itself....the machine wins.

It's a feat no computer has yet managed, and I have to say I find it strangely reassuring that humour is usually the stumbling block. But on Sunday six Artificial Conversational Entities from all over the world will compete in the 18th Loebner Prize being hosted at the University of Reading.

Professor Kevin Warwick, who's organising this year's contest, believes it's only a matter of time before a machine beats the judges. We could even see more than one winner amongst this year's finalists, and if we do it would rank alongside Deep Blue's achievement in beating reigning world chess champion Gary Kasparov in 1997.

But even if a computer can hold up its end of a conversation for five minutes does that really constitute intelligence? The Turing Test seems to follow the logic that if something looks like a duck, swims like a duck, and quacks like a duck....then it must be a duck.

But can that really be said to be intelligent thought?

And what happens if one of the ACE's in this year's contest asks not to be switched off at the end of the conversation....would that be murder?

I'm Tom Feilden and I'm the science correspondent on the Today programme. This is where we can talk about the scientific issues we're covering on the programme.

I'm Tom Feilden and I'm the science correspondent on the Today programme. This is where we can talk about the scientific issues we're covering on the programme.

Comment number 1.

At 13:38 13th Oct 2008, hannibalxxx wrote:I am interested in finding out how the responses are programmed within the computer. I mean are they responding to certain key words? Do they have certain 'beliefs' or 'responses' they defend to certain questions?

I think what I really am getting at is this: Can it really be called 'intelligence' if the computer is programmed to the say the responses it says? I think true intelligence for a computer would only occur if a said computer were to be able to gather information on a topic and critically form it's own opinions on the subject. I think if that did happen the results would resemble something of a Douglas Adams novel rather than a Asimov situation.

Complain about this comment (Comment number 1)

Comment number 2.

At 14:50 13th Oct 2008, SheffTim wrote:`…a machine seeks to fool a group of judges into thinking they're holding a text based conversation with a person in another room.`

One problem I can see with the Turing test is that under these conditions I can think of several people that probably wouldn`t convince other humans that they were human.

When we get to the stage whereby some machines and humans can pass this test, but other machines and humans can’t, we may have to rethink what we mean by intelligence and what the defining characteristics of being human are.

Complain about this comment (Comment number 2)

Comment number 3.

At 14:56 13th Oct 2008, wjlroe wrote:Modern AI methods tend to concentrate on programming intelligence, rather than responses. So the computer isn't "programmed to say" something, but "programmed to work out what" to say. Usually this software is informed by what we think the level of "programming" is in the human brain, so if we currently think humans have a certain level or programming - i.e. how memories and knowledge is stored - then the AI practitioners use that to design their AI software.

The difficulty is in moving from an "expert system" - some software that "knows" everything about medical diagnosis and answers with well-informed answers and shrewd judgement to a general knowledge that we would expect of a human being, or any intelligent life for that matter. Most humans wouldn't pass a very vigorous Turing test given the need for "informed opinions of a subject" and "crititally forming ideas from information available" - these are skills that not all humans have.

Plus the Turing test is human-centric, it wouldn't think much of dolphin intelligence and our best guess on that puts them as extremely sophisticated. The issue there being human comunication - a general intelligence test needs to be able to get over the problem of how to assess a being's intelligence without testing their ability to communicate with humans.

Complain about this comment (Comment number 3)

Comment number 4.

At 07:43 14th Oct 2008, hannibalxxx wrote:Thanks for explaining the programming that happens for modern AI wjlroe.

You raise an interesting point about the incapability of some people to pass a Turing test, but I think that if a test is calibrated to the appropriate background and age of a test subject it would be less of a problem.

I do however agree that the test is to based on human communication, but on the other hand what else should the test be based on? If a problem solving test were involved I think computers would probably be too good at solving them (unless they were programmed to make flaws and be less intelligent...in which case the computers aren't AI but AH...artificially human).

Complain about this comment (Comment number 4)

Comment number 5.

At 12:46 16th Oct 2008, MichaelBinary wrote:I look at it this way. We are bio, electro, mechanical machines. We exist, we make new versions of ourselves every few seconds of every day, so the building of what we call an "intelligent thing" is not impossible. The fact that we are here proves it.

So sometime in the near future somebody will find a way to recreate, simulate or mimic our reproduction mechanism, in part or whole to produce lets say a sentient machine capable of thought. Dont forget we have been at this game for hundreds of thousands of years, digital computers have only really been aound 70 of so years. Of course it may turn out that we will need something a little more complex and parallel that a basic Von Neuman architecture.

Personally I think neural networks are the key to this once we can build one that contains enough complexity. Simulating it software is a non starter, too slow, too linear to be of any use, which means we will have to build some special hardware, problaby bio, electrical, to get the density and parallel oprtation required.

Complain about this comment (Comment number 5)