My excuses for Letters to Sibelius

Some months ago, I was given CDs of a series of programmes produced by Radio New Zealand about the Finnish composer Jean Sibelius. Helen Munro, our Editor of Music had thought they might work on our Culture Zone. The first thing that I noticed was the name of the presenter: Marshall Walker. Marshall is a retired Professor of English at the University of Waikato in New Zealand and I first came across him some 18 years ago when I was writing my honours dissertation at university. Born in Glasgow, Marshall's love of Sibelius was nurtured by Ian Whyte, the man who founded the BBC Scottish Symphony Orchestra and the subject of my university thesis. I remembered Marhsall had been very helpful with my Ian Whyte research and I was excited at the prospect of re-connecting with him, even more so when I listened to the programmes and heard what a terrific series it is. The programmes form the backbone of our current Culture Zone and Marshall has kindly provided a little more context about his Letters to Sibelius.

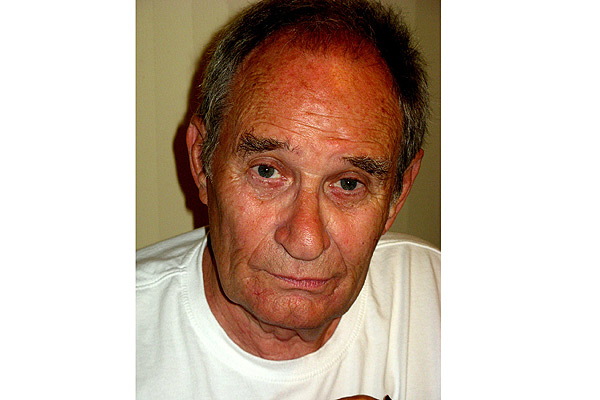

Marshall Walker:

Marshall Walker

Why letters? It takes nerve if not gall to write to an immortal.

'Who do you think you are? Don't be ridiculous. How could he possibly be interested in anything you might have to say?'

But there was encouragement too.

'Go ahead, you must. Tell him how you feel, what a comrade he's been. He won't mind. He'll be glad to hear from you'.

A lifelong addict of the music, I made a pilgrimage to Finland, visiting his special places, the birthplace in Hämeenlinna, the villa 'Ainola' where he lived for over fifty years, the forests and lakes near Koli in the north Karelia. When I got home Radio New Zealand asked for a programme about the trip. The responsible plod of a standard travelogue felt wrong. I wanted to tell him directly how momentous the sight of his places had been, what it was like walking up the driveway to 'Ainola', standing in his study, looking out over Lake Pielinen in the Karelia and seeing the music. It had to be as immediate as a letter and while I wrote it I became aware of his continuous presence throughout my life in Scotland, in Africa, America and New Zealand. So there had to be another letter and another, all kindly encouraged by my painstaking, world-class producer, Tim Dodd, gifted musician and virtuoso on the amazing digital recording machines, who worked such wonders with music extracts and sound effects. Encouraged, too, crucially by my wife, so patient with my exits into musical reverie.

Why Sibelius?

He's been a constant companion since we first met, the most potent contributor to what an Australian Aboriginal might call my songline. Doesn't everyone have a songline, with some songs stronger than others? I was twelve when he arrived; he was eighty-four, Finland's national treasure. Music classes at school were the last word in tedium. The teacher was an indomitably bleak, wiry woman with a voice like a ducks. We sat on creaky bentwood chairs with an acanthus-leaf pattern embossed on the seats which left itchy indentations on our behinds. While she bullied us mercilessly up and down the sol-fa chart we scraped our chairs on the wooden floor in protest but gave up when she didn't appear to notice.

One fine day we stumped dolefully into the music room to find that Miss Grumpy Sol-fa had gone. There was a brand new teacher, a smartly suited, keen-eyed, smiling young man. Curious and expectant, we settled quickly. The young man told us he was Mr Adams and without further preamble held up a twelve-inch 78 rpm record. I caught a glimpse of Francis Barraud's Nipper on the label. He was going to talk to us about tone and the descriptive power of music. The musicians on the record were Leopold Stokowski and the Philadelphia Orchestra with the renowned oboe player, Mitch Miller, contributing a regal cor anglais. We were going to listen to a modern piece by the Finnish composer, Jean Sibelius. It was called 'The Swan of Tuonela'. Strings filled the music room with the flow of dark water. The cor anglais began its lamentation, drawing us so completely into the eternal twilight of Tuonela that nobody made a sound even in the pause when Mr Adams turned the record over.

What was so special about the music?

The sound palette was different from anything I'd heard. There was a life inside it like nothing else. Oh, I loved other music by then, lots of it, but this was a new level of experience. I belonged in this music. I recognised it. It told the truth. Of course it sent me off hunting for everything else I could find by Sibelius. When I heard the Second Symphony for the first time in a Glasgow studio performance by the BBC Scottish Orchestra under Ian Whyte I wanted to shout, 'Yes, that's right. That's what it's like. That's what I mean too'. The Third Symphony enchanted me with the lilting dance and reflective grace of its second movement. With this theme in my mind I felt equal to anything. Then the First arrived. It was freshly in my mind on one of many visits to the isle of Lismore, my favourite piece of earth, so it became inseparable from sitting on a rock at the north end of the island watching Scottish weather flaunting its extremes in the Great Glen. The Fourth Symphony catered to all that was sombre in the world. The Fifth covered the gamut of human circumstances. The Sixth cleansed the spirit with cool water. The Seventh brought courage to face ultimate questions.

So I wrote these thank-you letters to Sibelius, thinking, too, of my gratitude to Mr Adams and to Ian Whyte and his orchestra who began the tradition of Sibelius performances richly maintained by Alexander Gibson, Colin Davis and Osmo Vänskä. In the Age of Management it seemed important to testify to the continuous, sustaining presence of an artist in a life.

Thank you, Radio Scotland, for bringing these New Zealand-made programmes home to where Sibelius first came into the music room of a Glasgow school.

Listen to Letters to Sibelius from The Culture Zone, on BBC Radio Scotland.

Comment number 1.

At 02:30 8th Sep 2010, kirsten allan wrote:The connection between word and music is seamless. Each enlivening the other.Through these letters we get a glimpse of Marshall's Sibelius diffused world and what a rich world that is.

Complain about this comment (Comment number 1)