By the Wildfowl and Wetlands Trust (WWT)

Brent geese winter wildlife spectacle WWT Castle Espie Wetland Centre

One of the toughest birds found in the British Isles

Where would you expect to find a voyager from the High Arctic? Probably not a Dublin park, but that’s exactly what happens every winter when thousands of little geese descend. It’s the light-bellied brent goose: arguably the toughest bird on the British Isles. So why does this wild creature pop up here?

To get to the answer, you need to take a trip back through a year in the life of a light-bellied - or more specifically, an East Canadian High Arctic light-bellied brent goose. Their story reveals a bird that lives life lived on the edge, charted through years of research by the Irish Brent Goose Research Group and the University of Exeter.

Strangford Lough by Sacha Dench WWT

Their name ‘brent’ derives from the Norse word for burnt - in reference to their charcoal coloured upperparts. The scientific name, Branta bernicla hrota, come from the fact that the brent goose used to be considered the same species as the barnacle goose, hence ‘bernicla’. The ‘hrota’ part comes from the Norse word for snore - ‘snore-goose’.

Light-bellied brent geese can be told apart from dark-bellied brent geese by their pale undersides and flanks. The difference is important, because subspecies migrate to different places.

Brent geese by Nigel Snell WWT

Polar explorers

This goose nests in the Canadian High Arctic, possibly further north than any other bird on the planet. They’re as little as 500km from the North Pole, about as far north as it’s possible to go, polar bear-dodging as they nest on bare rock and shingle. There’s a very brief window of summer in which to rear their young. Then, before the freeze comes, they must gather their families and leave. This family migration is in contrast to most other birds, but is seen in brent geese of all hues.

WWT Monitoring

First leg: crossing the entire Greenland ice cap

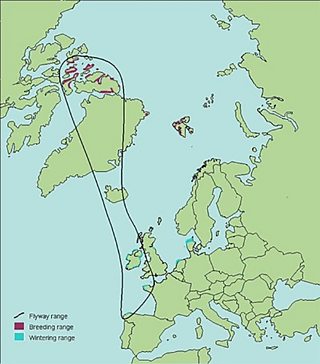

As if having one of the longest migrations of all wildfowl (4,500km) wasn’t enough, in order to get to their first wetland ‘service station’ the brent geese have the daunting task of flying over the Greenland ice cap; not a hospitable place.

It’s also not flat - rising to 2,500m above sea level, the geese need to put in extra effort to fly over. Sometimes, they have to land and waddle over the ice for a bit before setting off again. No wonder they’re so relieved when…

First stop: Icelandic wetlands

They arrive at the eelgrass beds of Iceland. Here, they can replenish their energy. Eelgrass (or Zostera) is a seagrass that’s one of the only marine flowering plants in the world. It grows on intertidal sand in ‘meadows’; these are submerged much of the time by the tide. They are biodiverse, providing food and shelter for seahorses, small fish and shellfish.

The geese favour eelgrass because both its stems and rhizomes are highly nutritious, especially the latter, which contain many water-soluble carbohydrates that are easy to digest.

Image by Richard Taylor-Jones

Northern Ireland and Strangford Lough

Refueled, the geese set off across the Atlantic to British shores. Strangford Lough in Northern Ireland hosts over 75% of the population of the geese during the late autumn and is now the most important site for this species outside the breeding season. It’s also the location of WWT Castle Espie Wetland Centre. Numbers peak at about 25,000 to 30,000 birds.

At Strangford Lough the geese mingle with other family groups. This sociability isn’t just for fun! Birds in families or even big groups of ‘friends’ tend to do better than single birds, because there are more eyes to watch for danger. Birds with less developed social networks spend more time walking around or looking up, when they would rather concentrate on feeding. But, with so many birds, the eelgrass doesn’t last forever.

Dublin

Now the geese abandon the depleted eelgrass and head south to spend some time as urban geese. This isn’t just a location change: as the birds venture into different habitats, they literally adapt their personalities. On their breeding grounds, the geese are nearly impossible to get near, yet in Dublin, they’re so tame you could almost pick one up.

This behavior is called ‘context dependent wariness’, where they recognise that arctic foxes represent a different threat level to a friendly Irish person.

There is another factor that would have influenced the geese spreading into urban areas originally. During the 1930s, a disease almost wiped out the population of eelgrass in Ireland. This might have been catastrophic for the light-bellied brent goose: instead, they managed to adapt to saltmarsh, estuarine plants, and managed grasslands.

Now, the threats to eelgrass come mainly from human activity, and seagrasses such as Zostera have declined 10% per decade since 1970 (IBPES 2019).

Back to Iceland for the refuelling

In March or April, the birds are off again to the High Arctic via Iceland. The Irish Brent Research Group has worked out some of the physiological constraints of their journey. To return to Canada, they have to put everything into developing their flight muscles. Some of their internal organs, such as their stomach, reduce in size after refueling because they don’t want to carry the extra weight. Only then can they make it back.

And finally… back to Canada

Even once back, there’s no let up. The landscape is frozen, so they cannot eat for several weeks. The females carry inside them the nutrients that will form their eggs all the way from Iceland, though they are only fertilised on the breeding grounds. The parents will incubate in a virtually starved state.

So much energy goes into it that after successfully breeding, the parents will often take the next year off to have a rest.

Brent goose conservation

It’s never been more important for us to understand how species like the brent goose will be affected by our climate crisis both here in the UK and in the high Arctic.

The UK conservation status of the light-bellied brent goose is Amber, meaning that they need to be carefully monitored. Twice a year, there is a census of the goose population - one in autumn and one in spring. The census is organised by the Irish Brent Goose Research Group.

Wetland habitats like eelgrass are vital for those species whose lives are heavily intertwined with our environment in a fragile balancing act. While brent geese are tough, they’re not indestructible. And many other species – that are not so adaptable - won’t be so lucky.