Keeping track of swifts

Kendrew Colhoun, senior conservation scientist at the RSPB NI, explains whats involved in keeping track of swifts.

This is the third year of a truly exciting project we have been undertaking examining the foraging behaviour and migration of ‘common’ swifts. Once much more common, swifts are these days sadly declining throughout the UK and Ireland and it has been a bit of a wrench to see fewer of these birds return late or not at all this May and June. It does appear to have been a poor ‘swift’ year - perhaps also for many of our long-distance migrants who winter in sub-Saharan Africa. Numbers of house martins, swallows and willow warblers seem to be down too. The job of conservation scientists like me is to try to understand more about these birds, especially why they may be in decline. Acquiring basic information on where they get their food in summer, winter and on migration, the routes and timing of migration and identifying important areas for them is an essential step.

Common swift in flight Killian Mullarney

At many of the sites we are tracking swifts at this stage in June, the adults have been making the best of the dry sunny weather and clutches of eggs are going to start to hatch any day now. Then things get really busy for them and my season begins too. In a collaborative project with Dr Chris Hewson at the BTO, we at the RSPB are investigating aspects of the behaviour of swifts that was previously impossible. It's now made possible because of the revolutionary development of tiny GPS tags that we can fit on a bird as small as 40g! Our first question is to understand where adults source their food when they are feeding chicks. Does this differ between and within breeding seasons, with weather and perhaps geographically? It is valuable, of course, to know where the birds forage at all times but it is much more preferable to catch birds at the nestling stage (the risk of abandonment is extremely low when there are chicks) so we concentrate on that.

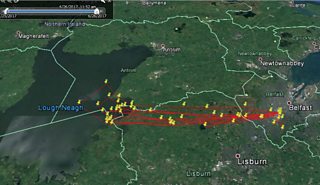

In Northern Ireland we have now several breeding seasons' worth of data. Re-catching a tagged bird and seeing where it has spent the last week or so finding food to feed its chicks is always a huge thrill. Amongst the sites we have been studying birds, the College of Agriculture, Food and Rural Enterprise (CAFRE) Greenmount campus (where Rodney Monteith has done such marvellous work at establishing a colony) is simply brilliant. We know these swifts forage mostly on Lough Neagh and periodically (probably associated with farming activities) on farmland around the campus. Of greater surprise to us has been the fact that the birds breeding about 25 miles to the east in Belfast are also making constant foraging trips to and from Lough Neagh to feed their chicks too. The lough must be a huge draw and supplies lots of juicy aquatic invertebrates. With the massive drop in flying insects generally (you only have to compare your number plates and headlights these days to what they used to be like after a long summer drive!) one wonders just how relatively more important aquatic invertebrates are than there used to be. Maybe the story of swift declines is not chiefly related to reduced nest site availability as is often stated. Both are likely key. So getting lots of samples of birds across years and sites enables us to pick this apart - to try to advance our understanding and see how we can apply that knowledge for conservation purposes.

Swift map Lough Neagh

Another equally thrilling aspect of the project - and actually the key job for the next month or so - is retrieving tags deployed last summer. We have had success with this already. It is amazing to think that we have frequent GPS locations of migrating swifts from summer through to the following spring just by using a little piece of technology weighing less than 1g and with a tiny solar panel! Breeding birds were tagged, fledged their young, migrated to Africa, returned and tags were removed when they were at the chick-rearing stage in the subsequent breeding season. Tags were removed, recharged and thousands of GPS positions showing where they had been for up to nine months. It's amazing that a 40g bird covers 10,000km between Northern Ireland and the southern half of Africa twice (not to mention the vast areas covered in mid-winter across the width of the continent) and spends much of its time on the wing. The main exception is the overnighting in their nests for two to three months for about seven hours a night.

They are seriously impressive birds! When we do our tag removals shortly (we know of tagged birds already back and breeding) we know they will contain lots of fascinating information and for the first time (because the tags have more memory capacity this time) we expect to get data on locations every six hours right from their departure in Northern Ireland in August through to returning in May. I really can’t wait. It's an exciting time to be studying such an amazing bird as the swift.

Find out more about the RSPB's Swift Project.