Remembering one of London's civil rights pioneers

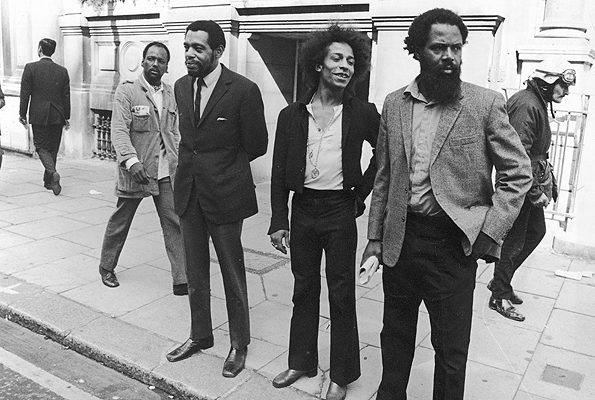

Thw owners of the Mangrove restaurant, left to right, Roy Hemmings, Jean Cabussel and Frank Crichlow

Looking back at a Notting Hill community stalwart, Frank Crichlow, who has died at the age of 78.

In the mid-1970s an old West Indian friend of my mother's - "uncle" John - took me to Notting Hill.

He wanted to introduce me, a North London Comprehensive boy, to the heart and soul of London's Black Community.

We ended up briefly at the Mangrove restaurant.

It was a pretty daunting place for a young teenager. People there had plenty of swagger and the venue had an intense but chilled-out ambience.

What really impressed me at the time was it was full of black and white people, who seemed to me to be very old (probably the same age as I am now!) who got on.

It seemed to defy the public conventions of the time that Black and White people didn't mix. It was a pretty intoxicating atmosphere.

"Uncle" John introduced me to the Mangrove as a place that had "fought the power" and won.

In terms of the emerging political consciousness of the black community in London, the Mangrove was a powerful antidote to the powerlessness that many young black Londoners often felt.

Within a few years that sense of frustration had spilled on to the streets of Brixton and later Tottenham in the disturbances in the early 1980s.

At the centre of the hubbub that day was a man with a scraggly beard who looked to me like a formidable figure.

I was briefly introduced, no words were exchanged, but I recall sensing that cool acknowledgement, familiar to some men who know and revel in their status.

By that time Frank Crichlow had become a well known civil rights campaigner whose restaurant had been targeted by Her Majesty's local constabulary on numerous occasions, allegedly as a drug den, only to be personally exonerated by the courts.

Unlike the modern besuited "activists", Crichlow came from a generation of people who became active because they felt the lick of a police truncheon and had become very familiar with the décor inside a police cell, mostly because they didn't appear to play by the convention of deference to police officers.

They demanded common courtesy and respect and when they didn't get it, they took to the streets.

In 1970 this led to the "cause celebre" at the Old Bailey, when the "Mangrove Nine", were tried for riot and affray.

The trial lasted for nearly three months and exposed a deep current of prejudice and dubious practice within the Metropolitan Police, long before Scarman and Macpherson.

When the "Nine" were acquitted many people thought it was a victory for common sense. In Notting Hill it was seen as a significant victory for the Black Community.

Crichlow's interest to the police didn't subside after this trail. Many saw his Mangrove Community Association, set up in the wake of this trial, as a red rag to the police bull.

The Mangrove restaurant

He was back in the courts several more times all centred on allegations about the Mangrove.

In 1988 the Mangrove was raided again and the consequence was its demise as a Community meeting point after nearly 30 years.

Defended by the redoubtable, Gareth Pierce, Michael Mansfield and Courtney Griffiths (both the latter now QCs) he was acquitted and eventually awarded damages of £50,000 by the Metropolitan Police.

The following year I became a journalist for the BBC and one of my first films was for the programme Heart of the Matter about the criminal justice system.

Courtney Griffiths recommended I speak to the man I'd met more than a decade earlier to understand the root causes of black youth disaffection and the reality of the criminal justice system at the time.

He was gracious although sceptical of any besuited BBC journalist, although he softened when I reminded him of our brief encounter all those years before.

Frank Crichlow and his generation had to cope with the disappointment and identify the problem of racism.

We are still working towards the solution of the more tolerant, caring and diverse community that he and others like him aspired to.

I’m Kurt Barling, BBC London’s Special Correspondent. This is where I discuss some of the big topical issues which have an impact on Londoners' lives and share stories which remind us of our rich cultural heritage.

I’m Kurt Barling, BBC London’s Special Correspondent. This is where I discuss some of the big topical issues which have an impact on Londoners' lives and share stories which remind us of our rich cultural heritage.