Why this rare child abduction case was a story worth taking apart

Andrew Bomford

Reporter for BBC Radio 4. Twitter: @andrewbomford

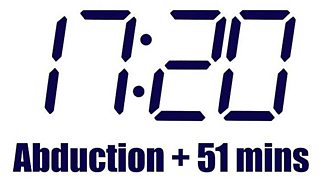

Every day this week, BBC Radio 4’s PM programme is broadcasting an episode of The High Street Abduction, a minute-by-minute retelling of events following the snatching of a little girl from a Newcastle department store last April. An accompanying long-form BBC News feature goes even further behind the scenes to recreate the successful police response to the Primark kidnapping. Here Andrew Bomford unpicks an unusual reporting project:

A representation of the abduction from Primark, Newcastle: CCTV footage was off limits

I wish I could say it was my idea, but it wasn’t. It was a parting gift from Joanna Carr, brilliant erstwhile editor of the PM programme, now head of current affairs at the BBC. Did I say brilliant?

But as briefs go it was characteristically short: that kidnapping in Newcastle - let’s take it apart.

There were several reasons why the case stood out, primarily how incredibly unusual it was. Child abductions are mercifully rare. Those carried out by children are almost unknown. I say almost - but more on that later.

Then there was the incredible speed - 90 minutes - within which this potential tragedy was brought to a safe conclusion by the police. Without knowing anything much about the circumstances, it was obvious that something remarkable must have happened that day.

But more than anything there was the simple thought that as a parent, this must be one of the worst things which could happen to you. To lose your child in a moment of inattention is a nightmare. But it’s something which can and does happen, frequently.

So many parents - me included - know that feeling of horror, fear and confusion, even if it only last a few moments. How much worse it must have been for this little girl’s mother.

The initial 101 call was logged by Northumbria Police call handler Kate McCafferty

First moves

I initially contacted Northumbria Police in June 2016, and pitched the idea of doing a series of radio reports for the PM programme. I said we would also like to do an article for the BBC News website - pretty much standard procedure these days in the age of multiplatform reporting.

But right from the germ of the initial idea, I was pretty sure that I wanted to write a long-read article, using Shorthand, a wonderfully immersive web publishing programme, which combines crisp text with beautiful visual imagery and video.

So, having successfully pitched that idea to the Magazine - the features part of the BBC News website - the project became a co-commission from the outset.

I think this made a big difference to my approach when researching and gathering material for the story. I wanted detail, real detail, much more detail than you might normally need on a more conventional story. It’s the pursuit of detail which can tease out the really interesting stuff.

For instance, I had no idea until we started interviewing officers that this case was ‘solved’ effectively by a constable who was not even involved.

It was a piece of extraordinary luck and coincidence that PC Graham Dodds happened to be reading the right piece of paper at the right time, and had the nous to connect it with the emergency unfolding a few miles away on his police radio at the time.

That’s the sort of detail which makes my heart sing, because it seems so unlikely that if you wrote it into a TV detective drama, it would be chucked out as unbelievable.

Minute-by-minute progress of the police search is recounted in the Magazine feature

The long game

I believe a key advantage we had in getting the project off the ground was a willingness to devote whatever time it took to realise our goal, and not impose any arbitrary deadlines.

I was anxious that this wouldn’t be just an end-of-trial background piece. But with any crime backgrounder, it’s a given that nothing can be reported until the conclusion of a trial.

Even with that reassurance for the police, it can be difficult to get officers to really open up and explain their role, their fears and their emotions. That sort of perspective often comes with time, so in all our dealings with Northumbria Police, I never applied pressure on them to get the story out by a particular date.

Journalists can become obsessed with finding a ‘peg’, a reason to do a story on a certain day in order to make it newsworthy. You need a certain amount of confidence in the strength of your story to ignore this urge. If it’s a good story, it’s a good story, no matter when it gets published or broadcast.

For the Northumbria force, there was clear value in telling the story, which worked in our favour. Any officer working on the abduction that day knew they were part of a remarkable bit of policing.

But even so, it took time to get the stars in alignment. The sentencing of the teenage girls came and went during the summer holidays, and as the autumn months progressed, many a conversation with the police veered from positivity to disappointment. There were certainly a couple of moments when it seemed like it was all off.

But I eventually boarded a train to Newcastle in November, and over an intensive three-day period carried out detailed interviews with every police officer we could find who had a role to play on 13 April 2016.

I worked closely with experienced Newcastle photographer Raoul Dixon, who knew the area backwards, and also with Jonathan Bargh, a press officer for Northumbria Police. Radio reporters tend to work solo, so it helps to have colleagues along to bounce ideas off.

The Bulger legacy

During the interviews, it became clear just how much the shadow of James Bulger fell across this particular story, and how much it played on the minds of the police officers involved.

The first mention of young James came in one of the earliest interviews I did - with the call handler, Kate McCafferty, who took the first 101 non-emergency call, reporting a missing child at Primark.

It was a “hair on the back of the neck” moment when she vividly described the fears running through her head the moment she first heard the mere mention that two teenage girls had been seen playing with the little girl before she was abducted.

What I found striking was that, aged 26, she was obviously too young to remember the murder of James Bulger, in 1993. She explained that she had studied the case at university. James Bulger has become part of modern history, I realised.

After that spine-tingling moment, it was remarkable how one by one, unprompted, almost every officer I spoke to took a moment to confess their fears at the time that they could be faced with an unfolding repeat of the Bulger tragedy.

It brought home to me why the police response was so concentrated, so urgent, and so effective.

Police Community Support Officer Shaun Cowan at the park where the toddler was found

Access to police material

What really brought their accounts to life though was the opportunity to listen back to the recordings of the 101 phone call, and the recordings of the police radio log, which gave a real-time insight into the lengths officers went to find the little girl.

It led to the obvious question of Northumbria Police. Could we broadcast these recordings?

Fortunately, by this point, after months of discussion, I think our relationship had reached a point of trust where the answer to that question was a simple “yes, why not?”.

The one disappointment in the access was the refusal by the police to allow the BBC to publish any of the CCTV film, which proved so crucial to tracking the teenagers and rescuing the little girl.

There was one image in particular we were desperate to show - the shot of the two teenagers leading the little girl by the hand out of Primark. It was uncannily similar to the infamous and iconic CCTV image of James Bulger being led away by his child captors.

And crucially, it was a key driver and motivating factor for the police, as the image was circulated to officers involved in the search via their phablets.

But police policy on the release of CCTV is quite rigid. It can be released to identify suspects during a live police investigation, and it can be released as evidence during a trial.

In this case the emergency was over so quickly that CCTV was never released at the time. And the teenagers pleaded guilty to kidnap and so there was no full trial. No amount of persuasion would convince the police to break policy and demonstrate why the image had the powerful effect it did.

We were lucky in that the mother of the abducted girl also agreed to be interviewed. It was the last interview we recorded, which seemed fitting. I was really struck by her quiet dignity, her eloquence, and her remarkable feelings of concern towards two teenagers who caused her such extreme anguish.

Packaging the story

The writing of the story, after all those months of preparation, came as a real pleasure, despite the subject matter.

The text was honed, polished, shaped and trimmed, during a series of meetings and editing sessions with Jonathan Duffy, and his team from the Magazine, who really helped to develop a sense of drama and pace by use of a clear time line, relating events back to the abduction point.

This technique gave the story a real driving force, and helped convey the urgency of the police response.

The radio reports, broadcast daily this week on the Radio 4 PM programme follow the story chronologically and are also published as Radio 4 podcasts - an increasingly popular medium for listeners.

One way of measuring the success of web articles is to see how long readers spend reading them. It can be hard to engage readers for more than 30 seconds, but the long read article The High Street Abduction has been securing engagement times of six minutes, which is quite rare.

The response from both listeners and readers has been gratifying. It is fantastic to know that in an age of 140-character tweets and short attention spans, there is still appreciation for a sustained piece of journalism.

Photography by of Raoul Dixon/North News and Pictures

Bite-sized news versus long form journalism: Make mine a Sicilian feast

In search of an urban legend: The man who squeezes muscles

Why telling the ‘full story’ of Islamic State group was my toughest assignment yet