Trust me I’m a Doctor: Anatomy of a primetime medical series

Alex Freeman

BBC series producer, Trust Me I'm a Doctor

Trust Me I’m a Doctor is unusual. The BBC Two programme doesn’t just report on science, it does its own medical research. Across five series, experiments have investigated everything from cholesterol busting and brain training to whether turmeric cuts cancer risk and supplements boost eyesight - using members of the public, and its own presenters, as volunteers. We asked Alex Freeman for an insight into the job of running a science research unit as well as a popular TV series:

A typical Trust Me episode will have 10-11 items, three of which are generally linked and based around one large experiment. These are expensive, difficult to run and take at least six months to set up. Before any of that can happen, of course, we have to come up with the ideas.

A lot of suggestions come in from viewers (thousands after each series), some from our own research - perhaps we come across something interesting where a key study is missing - and some from academics with whom we’ve worked before.

We’ve even had a couple of ideas from scientists, tweeting while they’re watching, saying: “I wish Trust Me would come and do x, y or z.” We’ve tweeted back and followed up.

Once we have an idea for a trial, we need to work up the protocol. For instance, how many participants will it take? This is a calculation done on the basis of the size of effect we expect to see and hence the number of people we would need in order to demonstrate that effect statistically.

We need to gauge how long it will need to run (typically six to 12 weeks) and the people we will need to use as volunteers - particular ages and risk factors such as high BMI.

Then we can cost the whole thing and see whether it’s feasible. I put aside a fair amount of budget for the ‘science’ of our experiments (tens of thousands of pounds). Universities help us out by providing staff time etc, but the cost of blood tests, analyses, drugs, transport for volunteers all have to be factored in.

Next we have to apply for ethical permission to run the study. This takes about six weeks in many cases, as university ethics boards often only sit once a month. It also takes a lot of paperwork. We have to show the scientific basis for the study, every detail of what we plan to do, how it will be analysed and how the results will be presented.

We also have to go through data protection and intellectual property contracts, especially where we are bringing together multiple institutions to run the study and do the analysis. Finally we recruit our volunteers (usually 60-100 of them).

Finding volunteers

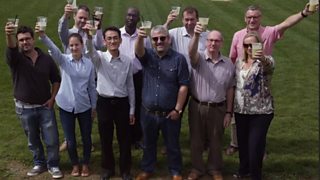

We’ve had about 250 volunteers involved in the current series (among them, our ten smoothie drinkers, above, for an eyesight experiment in episode one) and are currently recruiting 100 more for our next trial. Ethically, we have to specify how people will be contacted, what the inclusion and exclusion criteria will be and the statistical power calculation to show we’re recruiting an adequate number.

Some members of the team are very experienced at this and they work flat out. Generally people need to be screened by telephone first and then often face-to-face, sometimes with some basic tests. To get 100 people you need to have 150-200 turn up to screening, about 80 of whom might finish the experiment.

This is where being part of the BBC is a great help as local and national radio are hugely important for getting the word out. Our main presenter Michael Mosley (pictured, foreground, in top image with his regular co-presenters) is fantastic at doing radio interviews whenever he can, and that always generates a good spike in volunteer numbers.

Other than that we use all sorts of local networks (all the clubs you can imagine), social media and word of mouth. But it’s a specialised job and it doesn’t stop once we’ve recruited them. To keep people adhering to the experiment you need to keep phoning them every couple of weeks to check in. Our diligent researchers are on the phone to 100 or so people every week, hearing all about their lives.

Team work and scrutiny

Those big studies are a huge undertaking and we’ve developed a small core of about 15 people who are used to running them - it’s a real skill! Not everyone on the team has a science background, however. A few have science doctorates, and that’s really useful, but it’s equally important to have non-scientists who can see things differently.

We do quite a lot of self-shooting, and will film for each other’s stories. We have an ambitious digital presence, so everyone also sends photos from location to the team WhatsApp account, to be sent out on social media. It means we all know how each other’s stories are shaping up and can help out when there’s a problem.

For a programme like Trust Me, scientific integrity is the most important asset we have and our fantastic researchers work very long hours in the days before voice-over to double check every fact.

They are savvy and experienced enough to be able to get to the heart of controversial science. In fact we quite often target controversial areas, but we do it with our antennae alert for maverick voices, conflicts of interest or simply bad science. When we’re aware of those things we flag them to our viewers.

And if unforeseen problems arise - such as discovering a conflict of interest after broadcast, which has happened - then we use our website to update audiences. Online is also the place where we can give detailed information for interested academics as well as extra material for general users.

When it comes to presenting results, we try to approach it as we would publishing a scientific paper - only citing results that are statistically significant.

Results of an experiment into going gluten-free, displayed in an on-screen chart

Timing and surprise

Results from the big trials usually come in the final week or two of the edit. We allow contingency - things usually take longer to get going than hoped and there’s always something new we hadn’t bargained for.

This series our transmission was pulled forward by a week, for example, which means that we have been filming the results of our big experiment within seven days of broadcast each week. We now tend to finish the programme and deliver either the night before, or around lunchtime on transmission day (although our record was 57 minutes before going to air).

If all else fails we can broadcast straight from the BBC’s Pacific Quay HQ in Glasgow, where we’re based, rather than having to play the programme down the line to London.

We also usually have a ‘back up’ large scale study that can become the backbone of the programme if, for some reason, our plan A fails - either the results are disappointing or there’s a delay in results coming through. All this means that for a three-part series we’re running about six big academic studies, plus starting the six for the next series as we’re commissioned two series at a time.

Dr Kevin Tracey of New York's Feinstein Institute discusses the future of neurosurgery

Other regular items include our ‘future medicine’ strand which features clinical trials all over the world and brings its own inherent challenges. One trial in our last show had to be filmed over 18-months and another, now also recorded, won’t be transmitted for six months as we need to wait to follow the patient’s recovery.

Michael’s interview strand also needs long term planning - getting hold of world-leading experts in their field and matching their packed schedules with Michael’s own. By contrast, the speedy ‘viewers’ questions’ and first aid ‘lifesavers’ strand are a blessing to film!

One advantage of the tight delivery time is that each programme’s voice-over is only recorded a few days before transmission, and that allows us to ensure that everything’s bang up to date.

‘Real world’ experiments

Are we genuinely breaking new ground? Absolutely. It wouldn’t be worth the investment to simply repeat known results. Sometimes we’re scaling up from a small pilot or lab study and sometimes other trials have done something similar, but we’re always bringing something new.

That’s not always as difficult as it sounds. A lot of research funding falls into distinct camps: curing diseases, laboratory work to understand basic principles, drug company research. There’s not much for looking at health benefits of foods, or simply making people healthier in general.

Doing ‘real world experiments’ on a suitable scale, using ‘normal’ people and exploring everyday foods or other things where there’s no real big commercial incentive is quite a gap in the market. These are the studies that we all actually need done – so Trust Me is here to do them.

In part two of this blog, Alex Freeman answers questions on surprising results and audience response.

Episode three of Trust Me I'm a Doctor, 8pm, 22 September, BBC Two and on BBC iPlayer.

Reporting science: Professor Colin Blakemore