‘It’s like planning a dinner’: How they tried to attract women to computer programming

Charles Miller

edits this blog. Twitter: @chblm

This week’s BBC Academy podcast is taken from an event held at the BBC to encourage more women to apply for jobs in its Design & Engineering division.

The predominance of men in tech jobs isn’t unique to the BBC. Matthew Postgate, head of BBC Design & Engineering, describes it as “a decades-long issue” which is particularly bad in the UK: “in other countries there’s less of a bias with engineering professions than we have in the UK, so there’s absolutely no intrinsic reason why there should be that bias.”

So how did programming and other tech jobs come to be thought of as more the province of men than women? An attempt to find out was made by the American novelist and former programmer Vikram Chandra. In his semi-autobiographical history of programming, Geek Sublime: Writing Fiction, Coding Software, he traces the history of the tech business in the USA. If you go back far enough, he says, computer programming jobs were actually more likely to be associated with women than men.

Grace Murray Hopper (1906-1992), American computer scientist and US Navy rear admiral

In 1967, Cosmopolitan magazine was assuring its readers that computer programming is “just like planning a dinner ….Programming requires patience and the ability to handle detail. Women are “naturals” at computer programming.”

The now controversial analogy came from an impeccable source: Admiral Grace Hopper was a US naval officer and computer pioneer. She assured Cosmo readers that in programming, there’s “no sex discrimination in hiring”.

Hopper would have been aware of the dominance of female programmers in the development of early computers such as ENIAC (the electronic numerical integrator and calculator) built by the US army at the University of Pennsylvania at the end of the Second World War. Its six senior programmers were all women.

This female bias was partly a leftover from women’s traditional role as telephone operators, plugging calls through an exchange. Chandra quotes Nathan Ensmenger, author of another tech history who writes that “the telephone switchboard-like appearance of the ENIAC programming cable-and-plug panes reinforced the notion that programmers were mere machine operators, that programming was more handicraft than science, more feminine than masculine, more mechanical than intellectual.”

ENIAC programmers

The ENIAC programmers were far more intellectually and technically accomplished than switchboard operators: they were top mathematicians, pioneering a technology that would dominate society for decades. While their work wasn’t recognised at the time, in recent years it has been - in films and books and by their admission to the Women in Technology Hall of Fame in 1997.

So what changed after the ENIAC days to make women a minority in programming? It’s hard to give a precise reason, but the expansion and formalisation of the industry led to what one analyst in the sixties described as a greater incidence of “beards, sandals, and other symptoms of rugged individualism or nonconformity”.

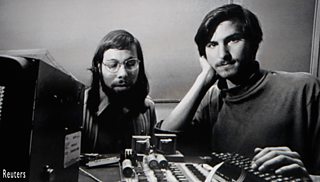

Apple founders Steve Wozniak and Steve Jobs

Californian ‘hippie capitalism’ became the ethos of Silicon Valley - with the often antisocial genius valued over the team. The male programmer, working all night, surrounded by empty pizza boxes and in need of a shower became a cliche of a thousand startup stories. The personal style of Bill Gates, Steve Jobs and now Elon Musk fed into the mythology.

So is the tech business changing?

Sheryl Sandberg, at Google and now at Facebook, and Marissa Mayer at Google and Yahoo! are influential voices. The recent resignations of Uber CEO Travis Kalanick and board member David Bonderman might suggest there is at least an awareness of some of the issues.

Awareness in itself is important according to Vikram Chandra because “one of the hallmarks of a cultural system that is predominant is that it succeeds, to some degree, in making itself invisible.”

Events such as the BBC initiative recorded in our podcast are further helping to remove that invisibility. Will we look back on the last fifty years as an anomaly in the history of technology as we return to a time when women are at least equally represented?

Chandra makes that seem entirely possible, pointing out that Admiral Hopper and the ENIAC programmers were themselves following in the footsteps of Ada Lovelace, the pioneering programmer and mathematician (and daughter of the poet Lord Byron) who wrote the first algorithm designed for execution by a machine.

The BBC’s Matthew Postgate isn’t expecting a quick fix: “I think it’s something that takes a while to change. There are lots of reasons why there’s that imbalance in the technology sectors in this country.” But changing it is “something the BBC is completely committed to achieving”.

BBC Academy podcast: How to get a job: Women in technology

A report and filmed interviews from the BBC event