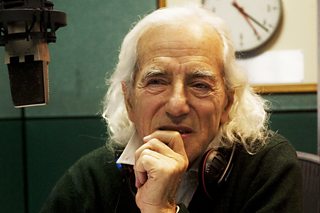

Seva Novgorodsev, broadcaster at the BBC for 38 years, tells us about his long and diverse career in radio presenting and shared his final thoughts as he hung up his headphones and handed in his BBC pass.

After 38 and half years as a BBC broadcaster – how do I sign off?

Going back to the beginning, it all started in 1977 when I joined the BBC in London as a Russian service programme assistant… Or perhaps it started two years earlier when I left Leningrad, USSR, as a refugee (our Soviet citizenships were annulled), first for Austria before going to Italy – from where I was planning a move to Canada to work as a navigator in the merchant navy. But following a chance meeting with an old acquaintance from Leningrad who worked for BBC World Service in London, I applied for a job at the Russian service and was accepted after passing a number of skills tests.

Because of my background of a saxophonist in a leading Soviet jazz band, I soon started to co-produce and co-present BBC Russian’s Pop-music Programme from London. Quite soon I became the sole presenter, while the programme evolved into Rockposevy.

I started off presenting Rockposevy in a straightforward DJ style, filling the intros to the songs with any relevant information. My main influences then were John Peel with his short and punchy style, and Terry Wogan with his very special use of voice and a meaningful pause. I also thought he was good with his jokes. So I bounced mine off a colleague who worked nights. If he didn’t immediately react with laughter, I changed them. All those jokes must have struck a chord with my listeners because they soon started to write to the BBC.

Writing to the BBC was an act of bravery, if not abandon, in the USSR: you could destroy your career with that one letter. Still many wrote directly. Others used people travelling abroad – for example, foreign students who studied in the Soviet Union posted those letters from third countries. Someone mailed a letter in a bottle – I don’t know how it was picked up in the Channel, but it was delivered as addressed: “To Seva Novgorodsev, BBC”. I kept them all, and in 2010 the BBC donated those letters to the Hoover Institution Archives in Stanford, California, where they fill 26 manuscript boxes. A future researcher can trace through them how, in the last years of Soviet communism, young people perceived the reality around them – be it in big cities or in the provinces – and how they started to seek personal freedom.

But in the first instance, these letters told me that Rockposevy had to be adjusted to the needs of my audiences. They wanted more background, they wanted to know what was going on in the world of popular music, they needed to understand the lyrics. So my programme became longer and more in-depth. There were 55 programmes on The Beatles, 12 hours profiling Led Zeppelin, six hours dedicated to Jethro Tull, and the list goes on and on. I translated some of the lyrics so my listener could understand what these different musicians were saying in their songs. Years later some of these translated lyrics were recited back to me by my fans who, it turned out, learned them by heart.

There was no way the BBC could conduct an audience survey in the Soviet Union so I had no idea about the audience numbers. After three years on air, I came across an article by an expert who returned from a research trip of the Soviet Union. His verdict on the state of the minds of the youth was short: “The youngsters tune in to Seva Novgorodsev”. That was the first time I got inkling about the scale of my audience.

Why did these young people come to my programme? I wanted them to be part of my show; I wanted it to be inclusive. While their parents and the schools and Komsomol dictated to them what they were supposed to do, I chatted with them as a friend. As I told them about people like them who were writing to me, I hoped they would feel themselves in a company of friends, and we could speak about the things that we knew were interesting to us, make jokes that we would all understand and relate to. We trusted each other as the programme aired on crackling shortwaves across the Soviet Union’s eleven time zones.

As well as the other Western radio stations broadcasting in Russian and other languages spoken in the former Soviet Union, the BBC World Service radio programming was jammed by the Soviets. Although there were some jamming-free periods, jamming was especially strong after the Soviet invasion of Afghanistan in 1979 and then during the growth of the Polish Solidarity trade union movement. What was going on in the shipyards of Gdansk and spread to all Poland refused to fit in the Marxist formula about the dictatorship of the proletariat – the facts contradicted the theory and they needed to be jammed. The Politburo weren’t scared for nothing.

Much later I was told that by special orders of the Central Committee of the Soviet Communist Party (which was the country’s highest power) the TV programme Vzglyad was created on the national (“central”) Soviet TV to lure the youth away from Rockposevy.

In 1987, at the height of perestroika, we launched the weekly music-and-chat show, Sevaoborot – the first such show in Russian. When I look at the list of my contacts which grew to thousands of names during the Sevaoborot years, I can hardly believe it. There is a huge number of amazing people – from musicians and writers to scientists and famous defectors. We spoke informally. I met with the guest two hours ahead of the broadcast. We would just chat in the Bush House cafe, so the guest could get used to me and I could get used to them. I would watch out for any hints of a subject for our conversation on air. The strength of the programme was, again, the trust between the presenter and the guest. I think what was happening was not even journalism in its strict definition but what I would call a conversational literature. Sevaoborot went on air every week for 19 years.

In February 2003, BBC Russian launched BBSeva. There were a few reasons for creating this programme. BBC Russian was going through the reduction of shortwave broadcasting which was proving to be an expensive and outdated medium. Short of other distribution options, the BBC was trying to work directly with local radio stations in Russia – our potential re-broadcasters. So we needed a format that would fit their style.

Editorially, BBSeva was conceived as a review of the day’s news agenda – but in a normal, human language. The way we saw the programme’s long-term goal was to make the world of politics more accessible to our listeners, to bring the world closer to Russia and Russia – to the world.

Strange as it may seem, I had always tried to keep away from politics as something not quite worthy. Nor did I have any deep knowledge of the subject. So once again I was one with the people, and it was on behalf of these people that I asked simple, and sometimes naive, questions - but in the background there was an expert and very often it was our editor at the time, Andrey Ostalski.

Back then, the programme might have seemed too an informal way of discussing serious political issues - we hadn’t done a lot of that at the World Service. But as BBSeva was reviewed after a few months’ broadcasting, colleagues from other language services whole-heartedly supported it, saying that they would have loved to have such a programme themselves. Phew.

BBSeva was to be part of the BBC Russian output for the next 12 years and a half. It was among the select few radio programmes which moved online to the website bbcrussian.com after BBC Russian stopped traditional radio broadcasting. Its last edition was aired from Pushkin House in London on 4 September 2015.

So how do I sign off? How do I say goodbye to my listener? With their response over these decades, my audience have also shaped up my broadcasts - and my life. So I’ll say just this: we are all temporary but the BBC is forever.

Seva. Seva Novgorodsev. London. BBC.

Seva Novgorodsev was a radio presenter for BBC Russian Service.