ITV’s submissions to the Government and the Commons Culture Select Committee on Charter Review suggest that it inhabits a parallel universe where BBC One’s editorial strategy is to ape ITV and chase ratings at all costs. ITV also seems to have abandoned its earlier support for ‘competition for quality’ between BBC One and ITV, described as: ‘a unique feature of the UK television market, sustaining genres such as high-end drama and free-to-air sport, underwritten in large part by the entirely different funding sources for the two channels’. It now advocates less, not more, choice and competition as a good outcome for audiences and for UK broadcasting.

ITV’s solution to the BBC’s success is to tie it down with prescriptive regulation and design a system that says that its services should be scheduled by its competitors rather than for its audiences. ITV claims that it doesn’t want a ‘narrow, unpopular, market failure’ BBC, but imposing its proposed regulatory regime would risk that very outcome. Given what’s at stake here, ITV’s claims merit close examination, as do their policy prescriptions.

What is the problem ITV are trying to fix? And who would benefit from the proposed solution? First, let’s define our terms.

1. What is distinctiveness?

Distinctiveness is an important characteristic of the BBC and all its services. It’s one of the things that justifies the BBC’s public funding. Sensibly defined, distinctiveness should be a clear requirement for all BBC services in the new Charter & Agreement, as the Government’s Green Paper suggests. But distinctiveness can have different meanings for different people, whether they are audiences, competitors or policy-makers.

Distinctiveness should, in our view, be judged at the level of services rather than programmes. It does not make practical sense to say that the BBC should only make a programme if another broadcaster never would. That would mean that when ITV made Broadchurch, the BBC would have to stop making Happy Valley. Or it would mean that we should stop doing EastEnders because ITV does Coronation Street.

Nor does it make creative sense. The BBC should not start with a gap in the market, and try to fill it. It should start with its public remit and the creative idea, and then deliver programmes that fulfil them. The fact that the BBC makes some of the same types of programmes as the commercial sector means there is ‘competition for quality’ that benefits all sides and explains why this country has some of the best television in the world. If we withdrew, it’s likely that commercial broadcasters would reduce their investment too and audiences would have less choice. ITV is already spending less in real terms on original UK content investment, despite its strong advertising revenues and profits.

So, we propose two clear tests (not one as ITV suggest) - that every BBC programme should aspire to be the best in that genre, and that overall the range of programmes in every BBC service should be clearly distinguishable from its commercial competitors. We and the BBC Trust have suggested criteria that could be used (alongside performance indicators) to test this distinctiveness:

- creative and editorial ambition—the licence fee gives the BBC freedom to take creative risks and deliver services that are high quality, challenging, innovative and engaging;

- high editorial standards—meeting the public’s high expectations of fairness, accuracy and impartiality;

- range and depth—providing a wide range of genres and the best programmes in each genre, in order to serve all licence fee payers; and

- high level of first-run UK originated content and supporting home-grown ideas and talent.

2. What’s the problem?

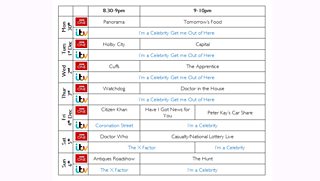

As the saying goes, ITV is entitled to its own opinion, but not its own facts. My first response to the claim that BBC One is aping ITV and chasing ratings at all costs is: ‘please watch the channels’. The peak-time schedules last week, for example, couldn’t be more different – with ITV1 stripping I’m a Celebrity in the 8.30/9-10pm slot for five days, whereas BBC One showed new specialist factual programmes on science and health (Tomorrow’s Food and Doctor in theHouse), new drama (Capital and Cuffs), as well as Panorama, comedy and factual entertainment.

The BBC’s services are distinctive and have become more distinctive than ever. Thirty years ago, a fifth of BBC One’s peak-time schedule consisted of expensively acquired US series, like Starsky and Hutch, The Dukes of Hazzard, Dallas, Kojak and The Rockford Files.Today, it is zero.

In terms of public perceptions, BBC One rates highest for quality when compared with 66 major television channels in a major global survey carried out in 14 countries [1]. Contrary to ITV’s assertion that BBC One is ‘widely acknowledged to be the BBC’s least distinctive TV service’, the channel comes out top on all Ofcom’s distinctiveness measures, ahead of the other PSBs for programmes being ‘different to what I’d expect on other channels’ and for ‘showing programmes with new ideas and different approaches’ [2]. BBC One’s ‘fresh and new’ scores for programmes – the agreed way to measure audience perceptions of distinctiveness – have risen over the last five years from 64.7% in 2010/11 to 71.6% in 2014/15 [3].

I don’t have the space here to address all of ITV’s specific claims (more to follow on daytime, Wolf Hall etc), so let’s just deal with some of the biggest.

‘’…the BBC will increasingly outspend its rivals with highly popular and often derivative and indistinct content…’’ (p.5 of ITV’s response to DCMS Charter Review consultation)

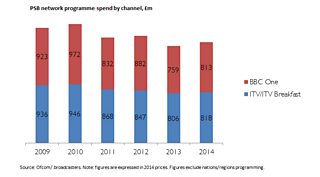

Not true. The BBC spends broadly the same on BBC One network original programming as is spent on ITV (in four of the last six years BBC One’s spend has been lower than, ITV’s including in 2013 and 2014) [4], we have a much more diverse schedule, and we have higher reach and a bigger audience. [5] Far from “chasing viewing share at all costs”, BBC One has developed content which is both distinctive and popular, as ITV recommends and the facts bear out.

"…the evidence shows that BBC1 in particular has become less and less distinguishable from its rivals over the current Charter period…There is an over-reliance on long-running programmes on BBC1 with little space in the schedule for new and more distinctive material’’ (p.6, ITV’s response to BBC Charter Review consultation)

ITV is right to say that the BBC Trust have challenged the BBC to show greater creative ambition and take more risks on BBC One. But ITV is wrong to say that we haven't responded to this challenge and that there has been a failure to deliver a more distinctive service. Making brilliant new programmes that are both popular and distinctive isn't an easy task, particularly when faced with a c20% cut to licence fee funding. It's not surprising that the further strengthening of the BBC One schedule has taken time rather than being achieved overnight.

ITV forgot to mention that the BBC Trust’s service review in 2014 said that the growth in BBC One and BBC Two’s 'fresh and new' scores since 2010 has been impressive and that the scores demonstrate that viewers of programmes on these channels are finding them, on average, more distinctive. This shows regulation is working.

BBC One (named ‘Channel of the Year’, again) is so popular at the moment for the very reason that it is both high quality and distinctive. This year we’ve seen a channel that has consistently pushed the creative boundaries with shows like The Hunt, Dr Foster, DIY SOS –Homes for Veterans, Bake Off, Strictly, River, Peter Kaye’s Car Share, Life After Suicide and Panorama, with more to come in the winter schedule. Which other channel would have dedicated Saturday nights to ballroom dancing, or placed rural affairs at the heart of its Sunday evening schedule?

Despite a real terms budget reduction, the number of unique shows [6] in the BBC One schedule has stabilised since 2010, not continued on a ‘trend downwards’ as ITV suggest.

"Any content or genre that does not maximise audience share has been marginalised or removed altogether from BBC One’’ (p.6, ITV’s response to Charter Review consultation)

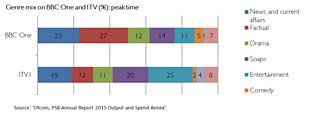

BBC One shows a much broader range and depth of content than ITV. BBC One broadcasts more than double the number of hours of factual programming in peak time compared with ITV, with the reverse being true when looking at the mix of entertainment across both channels (nb 2% of the licence fee is spent on TV entertainment programmes). When you combine news and current affairs with factual content on BBC One, the combined total is an impressive 50% of peak time.

BBC One’s commitment to specialist factual content (Music and Arts, History and Business, Science and Natural History, and Religion), remains undiminished with programmes like The Hunt, Rome’s Invisible City, Earth’s Natural Wonders, 24 Hours in the Past, Big Blue Live and Remembering VE Day. While the number of hours of specialist factual programming has gone down on BBC One, the average cost per hour of those programmes has increased.

The volume of specialist factual on the BBC’s channels overall has seen significant growth, including a 30% increase of new specialist factual programmes in peak-time on BBC Two. In 2014, the BBC showed 569 hours of new specialist factual in peak vs 70 hours on ITV1. This reflects a deliberate editorial strategy, with a focus on increasing the impact of ‘fewer, bigger’ specialist factual programmes on BBC One and adding extra depth and range on BBC Two, Four and Three. In October 2013, we said we would spend 20% more on TV arts by the end of this Charter and we will meet this commitment.

It’s also wrong for ITV to say that the ‘amount of peak-time current affairs on BBC One is little different now to ITV’. According to Ofcom data, BBC One broadcast close to 30% more current affairs hours in peak than ITV in 2014.

3. What’s the right solution?

We don’t recognise the problem diagnosed by ITV but there are some things where we agree. As argued above, the new Charter & Agreement, and future service licences, should set out clear distinctiveness requirements for all of the BBC’s services, with proper external oversight and remedies. Regulation of the BBC must be effective but not prescriptive and paralysing. Regulation shouldn’t tell us how to do our job, rather than the job we should be doing. Today, the BBC operates under 26 different service licences, running to more than 200 pages - with around 160 statutory and non-statutory quotas and separate conditions.

When it comes to regulating creative freedom, there is clearly a careful balance to be struck. Having cut the BBC’s funding if you then freeze the BBC in aspic with very detailed regulations, there is a real danger that you end up with a diminished BBC. While a BBC that paints by numbers and ticks any number of boxes may be good news for commercial competitors, it would not deliver the genuine creativity and innovation valued by licence fee payers.

Two of ITV’s regulatory proposals, in particular, demonstrate why the next Charter must be designed by the public interest not lobbying interests:

1) The BBC should effectively be told how to schedule its entertainment, drama or news programmes. This may be convenient for ITV but not for those who fund the BBC and it would undermine editorial independence. ITV criticises the BBC for ‘aggressive scheduling’, citing BBC One’s Silent Witness targeting ITV’s Broadchurch as an example of the dark art. The accusation is that the last series of BBC’s long-running drama series was scheduled to go head-to-head with series two of Broadchurch in January 2015. A closer look, however, reveals that the last three series of Silent Witness (and five of the last six series) have all been scheduled in January, whereas the first series of Broadchurch screened in March and April 2013, with the second series being moved to January. So who is scheduling against whom? It would appear that ITV is not immune to a bit of ‘aggressive scheduling’ itself with regular delays to the start of its 10pm news bulletin apparently designed to target the BBC’s Ten O’Clock news bulletin.

2) A ban on the BBC showing any acquired content or formats (so no more University Challenges, Apprentices, Dragons’ Dens) on BBC One or BBC Two. Perhaps this proposal should be re-named: ‘‘The BBC can’t have these programmes, because ITV wantsthem’’. Including films and global formats, less than 5% of BBC One peak network schedule is acquired. But these shows are loved by licence fee payers and have a place in the BBC One schedule. The proposal would also reduce competition in the programme supply market.

Finally, ITV opposes the decision to increase investment in BBC One drama by £30 million on the basis that it could crowd-out its own investment. This misreads the competitive dynamics at play in UK broadcasting, where the BBC’s presence stimulates commercial investment through ‘competition for quality’ and vice-versa. Two years ago, ITV said:

"At its distinctive, innovative best, the BBC has consistently demonstrated – whether in its Olympics coverage, its natural history output, comedy or dramas – its ability to deliver large audiences with distinctive and innovative output. This forces ITV to respond."

Ofcom’s analysis shows that the level of BBC (and especially BBC One) investment in first-run original programmes is correlated with investment in ITV. ITV's advertising revenues have increased and its profits have risen by more than 550% since 2009 to over £700m in 2014. Despite this, ITV has reduced its investment in real terms in original UK content over the period. With the BBC’s funding under pressure in real terms, ITV faces less of an incentive to invest.Does ITV want the freedom to continue this investment trend in key genres like drama, while at the same time constraining the BBC’s ability to respond? Far from crowding out commercial investment, we need a strong BBC as the cornerstone of PSB and the main driver of investment across the system.

[1] Populus for the BBC, September-October 2013 in 14 countries (representative sample of 500 adults 18+ per country)

[2] Ofcom, PSB Annual Report 2015

[3] Research carried out independently by Gfk for the BBC and involving a panel of c.20,000 adults.

[4] The BBC spends more on nations and regions programming and does far more hours.

[5] BBC One average weekly reach 78% / share 22%: ITV reach 69% / share 15% (ITV inc.+1). Reach is 3 mins+.

[6] Unique titles are defined as titles that were broadcast just once in a given time period. Any spin-off programmes associated with a title are not categorised as unique