Forty five years on from the swinging of the legendary "Beeching Axe", when many stations and track disappeared from the national rail network, the railway scene of the Black Country has changed out of all recognition compared to its halcyon days of the early twentieth century, with some of the region's major towns losing their rail connection completely.

Steam engine at Dudley

But should the wholesale decimation of the region's railways be placed at the feet of Dr Beeching?

With the 45th anniversary of the publication of the "Reshaping of British Railways", or "Beeching Report" as it is more commonly known, it seems appropriate to assess the extent to which it reshaped the railways of the Black Country.

Haemorrhaging money

The backdrop to the Report was that the nationalised British Railways were losing around £30 million per year by the early 1960s despite the British Transport Commission's 1955 "Rail Modernisation Plan" that looked to inject £1.2 billion into the system to boost flagging returns.

Largely as a result of the failure of the investment approach to return the rail network to profitability, the then Minister of Transport Ernest Marlpes recruited Dr Richard Beeching in 1961 to the post of chairman of the British Railways Board with a brief to resolve the haemorrhaging of capital through the rail network.

Flooding at Walsall station in 1886

The birth of the Black Country rail network

The railway network through the Black Country had largely developed during the latter half of the nineteenth century with a succession of railway companies keen to harness the potentially rich industrial traffic of the region and connect it to the industrial North and ports for distribution throughout the Empire.

The Grand Junction Railway (GJR) was the first to pass through the region in 1837 with a line passing Wednesfield and Walsall, albeit on their outskirts, on its route from Merseyside to London.

Numerous companies were soon to follow and feed the region with raw materials, and transport goods around the country in addition to getting their share of the lucrative coal traffic that was being mined heavily in the region.

The Oxford, Worcester and Wolverhampton Railway and South Staffordshire Railway began to link the major towns of the region with stations opening at Dudley (1860), Walsall (1847) and Wolverhampton (1852) with a myriad of smaller rail companies opening branches serving the smaller industrial towns and villages such as Halesowen (1878) and Stourbridge (1852) along with a plethora of privately owned colliery lines and tramways, such as the Earl of Dudley’s colliery line through Pensnett.

Pelsall station sign seen in 2007, it closed 1965

A rush for riches

Such were the perceived traffic riches of the area that numerous small towns and villages benefitted from two stations operating under two different rail companies: Princes End, Tipton, Great Bridge, Willenhall and Wednesbury being prime examples.

By 1921 this competition was leading to many of the smaller companies running at a loss as there was not significant passenger numbers for the large-scale duplication of routes.

Indeed, from the turn of the century, even the high volume coal traffic was beginning to diminish with many of the Black Country’s pits beginning to near exhaustion.

The result was the Railways Act 1921 which proposed the 'Grouping' of all railway companies into "The Big Four" which would reduce the competitive nature of the railway companies as each would be allocated to a particular national region in which to operate.

The Black Country's railways were to be operated by the Great Western Railway (GWR) – who had largely monopolised the East of the region - and the newly formed London, Midland and Scottish Railway (LMSR).

This move however did little to stem competition and attempts to exploit new populations.

Steam engine at Dudley

The rail system goes into overdrive

With the coming of the Second World War, the rail system was put into overdrive in the region with its factories turned to feeding the war machine. The 6 years of war took its toll on the network as it had been used relentlessly, but had received no investment leaving its stock, locos and infrastructure exhausted: a problem that was to become the government’s responsibility in 1948 with the Nationalisation of the entire network.

To further compound the problem, the post-War 'Boom', along with advances in engineering, had opened up the prospect of motor car ownership, coupled with the emergence of the road haulage industry and bus travel considerably reduced the demand for both passenger and goods services on the railways.

Whilst some 'rationalisation' of the region's rail network had occurred earlier in the century – the London and North Western Railway closure of the Princes End Branch in 1916, the LMS closure of the Wolverhampton – Willenhall – Walsall line in 1931 and the GWR closure of the Kingswinford Branch in 1932, diminishing traffic and urgent need for investment had created a significant problem for the now publicly owned railway and the aforementioned Rail Modernisation Plan of 1959 had done little, if anything, to resolve the issue with its attempt to increase revenue through expenditure.

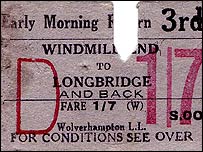

3rd class return from Windmill End to Longbridge

Roads seen as the future

It was into this arena that Minister of Transport Ernest Marples, a firm advocate of road transport who had overseen the opening of the first motorways – the Preston Bypass in 1958 and the first section of the M1 in 1959 and himself a two-thirds shareholder in the road building civil engineering company Marples, Ridgeway and Partners – who felt that the view of private industry was needed and appointed ICI Technical Director Dr Richard Beeching Chair of the British Railways Board in 1961.

Beeching and his team set about analysing traffic usage throughout the rail network, both freight and passenger, and in 1963 published the 'Reshaping of British Railways' which found that half of Britain's 7000 stations produced just 2% of railway passenger traffic and hat 95% of overall traffic was carried upon just 50% of the network.

The solution proposed was to close over 2000 stations and 5000 route miles nationwide and drastically change goods practices by the creation of freight concentration depots and thus doing away with many goods stations and the total decimation of goods sidings and yards at local passenger stations.

Baptist End Halt closed in 1964

Several steps too far

Whilst some of the passenger closures in the Black Country were economically justified – for example, the study of passenger usage on the 'Bumble Hole' line that ultimately led to its demise showed that only 1 person a day used Windmill End station, catching a train to Dudley!

Rather more questionable was the total closure of Dudley Station (only to re-emerge as a rail concentration depot, itself closing in 1989) and the decimation of services to Walsall – a town that had Beeching had his way would have lost its rail connection completely.

Both major and branch routes were identified for closure, among them;

New Street – Sutton Park – Walsall

Walsall – Dudley

Walsall – Rugeley Trent Valley

Swan Village – Great Bridge, Stourbridge – Worcester – Hereford.

Others, such as Stourbridge – Wolverhampton Low Level were already earmarked for closure at the time of writing the Report with a number of stations closing some months before its publication.

Dr Richard Beeching in 1964

Beeching unrepentant

Whist Beeching wasn't solely responsible for the decimation of the railways of the Black Country, the Report did put an end to the extensive nature of the region's rail system from which it would never recover.

Unrepentant even with the benefit of hindsight, in an interview on the 20th anniversary of the Report, Beeching stated that his only regret was that two of the lines recommended for closure hadn't been forthcoming - one was the Birmingham to Walsall route which would have left Walsall completely without a rail connection.

===

Andy Doherty from Rail Around Birmingham and the West Midlands website is passionate about the rail industry in the West Midlands. Last year he wrote 'Rail Around Birmingham: Central Birmingham' published by Silver Link and his forthcoming book is 'Rail Around Birmingham, the Black Country and South Staffordshire Routes'. For more information see the Rail Around Birmingham and the West Midlands website.

The BBC is not responsible for the content of external websites