What are light waves?

Welcome to science world! Today, we're going to have a look at a particular type of wave - a light wave. Who knew so many different things travelled in waves?

A light wave travels faster than anything else - even sound. That's why you see lightning before you hear thunder, but what's going on? How does it work? Well, that's why today we're asking 'what are light waves?'

Welcome to wave world! Light is a type of electromagnetic radiation that can be detected by the eye. It's a transverse wave which, unlike sound waves, can travel through vacuum. Which is handy because space is a vacuum, so if it couldn't light from the Sun wouldn't reach Earth and none of us would exist.

When light is reflected by a plain mirror, we find that the angle of incidence equals the angle of reflection. This is called the law of reflection. And light can even bend.

Glass is denser than air, so when light passes from air into glass, it slows down and bends towards the normal. Light speeds up again as it passes from glass into air, because air is less dense than glass. The ray is now bent away from the normal.

So, remember this: use F, A, S, T. When light gets faster, it bends away from the normal. When it gets slower, it bends towards the normal. Bending of light in this way is called refraction. Now that you have seen the light, back to ground control.

So, light is another thing that travels in waves, but at different speeds according to the density of the substance it's travelling through.

See you next time in science world!

(CRASHING SOUNDS)

Who left that guitar there?

Light is a type of electromagnetic radiation that can be detected by the eye. It travels as a transverse wave. Unlike a sound waves, light waves do not need a medium to pass through, they can travel through a vacuum.

Light from the Sun reaches Earth through the vacuum of space.

A short video explaining the concept of light waves.

Light is a wave, like sound or water waves. But unlike sound or water waves, light waves don't need particles to travel through.

Light from the Sun travels all the way to the Earth through the vacuum of space.

Light waves are a million times faster than sound - that's why, when you see a firework go off, you see the flash before you hear the bang.

The speed of light

The speed of light in air is very close to 300 000 000 m/s. which is nearly a million times faster than the speed of sound, which is 340 m/s. 300 000 000 m/s is often written as 3 x \(10^8\) m/s.

The very large difference between the speed of light and the speed of sound explains why you:

- See lightning before you hear it.

- See a distant firework explode before you hear it.

- See a distant hockey stick hit a ball before you hear it.

Just how fast is 300 000 000 m/s?

300 000 000 m/s (or 300 million m/s) is approximately the same as 670 000 000 miles per hour (or 670 million miles per hour).

That means in one second light travels a distance of 300 000 000 m – which is about seven and half times around the world, in one second. Which is pretty fast! Not even Superman managed that. In fact, nothing can travel faster than the speed of light.

By comparison, sound travels just 340 m in one second, about the length of three and a half hockey pitches.

The table summarises some similarities and differences between light waves and sound waves:

| Light waves | Sound waves | |

|---|---|---|

| Type of wave | Transverse | Longitudinal |

| Can they travel through matter (solids, liquids and gases)? | Yes (if transparent or translucent) | Yes |

| Can they travel through a vacuum? | Yes | No |

| How are they detected? | Eyes, photographic film, light detectors or image sensors | Ears, microphones |

| Can they be reflected? | Yes | Yes |

| Can they be refracted? | Yes | Yes |

| Speed | 300 000 000 m/s (300 million m/s or 3 x \(10^8\) m/s) | 340 m/s |

Light rays and ray diagrams

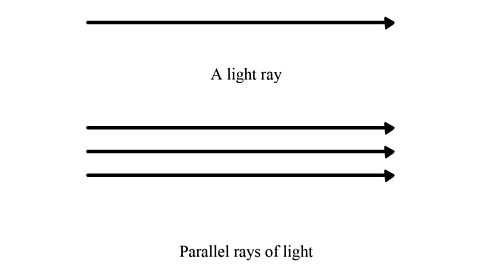

Light travels in a straight line. When drawing a light ray:

- Use a ruler and a sharp pencil to draw a straight line.

- Add an arrow to show the direction the light is travelling.

A ray diagram shows how light travels, including what happens when it reaches a surface.

In a ray diagram, you draw each ray as:

- a straight line

- with an arrowhead pointing in the direction that the light travels

Remember to use a ruler and a sharp pencil.

Lasers are a good example of light travelling in straight lines.

The pinhole camera

A pinhole camera consists of a box or tube with a translucent screen at one end and a tiny hole (the pinhole) made in the other end. Light enters the box through the pinhole and an image is formed on the translucent screen. The image is upside down and smaller than the object.

A pinhole camera is another good example of the fact that light travels in straight lines. They can be useful to look at the image of a dazzling object such as the Sun which you should never look at directly. Forming an image on the screen makes watching an eclipse safe.

Shadows

Shadows are also formed because light travels in straight lines. When an object that will not allow light to pass through it (an opaque object) is placed in front of a light, a shadow is cast on the ground or a screen behind it. The object stops the light reaching the ground and the shadow is the shape of the object.

If light could curve around the tree, the shadow wouldn’t form. A shadow shows that light travels in straight lines.

Solar eclipse

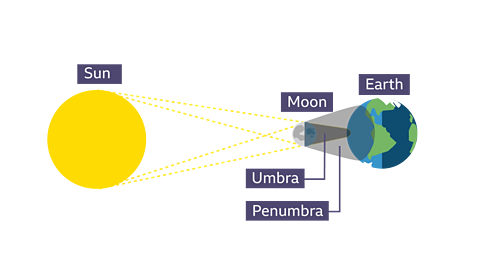

An eclipse of the Sun, or Solar Eclipse, occurs when a new Moon passes directly between the Sun and the Earth, blocking out the Sun's rays and casting a shadow on regions of the Earth. As a result, daylight briefly turns to darkness.

The total shadow or umbra is the shadow's dark core. The partial shadow or penumbra is the lighter outer part of the shadow.

A total solar eclipse happens when the Moon casts the darkest part of its shadow, called the umbra, on Earth. The Moon appears to cover the entire disk of the Sun. However, you only see a total solar eclipse if you are in a region covered by the Moon's full shadow, its umbra. Those outside the path in the partial shadow, or penumbra, see a partial eclipse.

Well, the moment has come and gone and it was truly as spectacular as described.

Now, when the moon started to creep up and block the sun, that alone was an amazing experience. Seeing the sun on the form of a crescent, which normally we only see the moon as.

The real moment came up quickly, once the moon completely blocked the sun's surface, the whole environment here changed. It became instantly darker, the temperature dropped drastically and everyone gathered together just in absolute awe. They were gasping, shouting 'wow' and just laughing at the marvel they were witnessing.

But the true amazing part of this, and what made the total solar eclipse so different from witnessing a partial eclipse, was seeing how bright the corona - which is that ring of light - how brightly that shined. And I think that's what everyone was just so in awe of for those two minutes and forty seconds, experiencing something that most here had never seen before. It really was just a true moment of joy that was amazing to see everyone here witness together.

The next total solar eclipse to occur in the UK will be on 23 September 2090. It will be visible in Cornwall and much of the south coast of England and last 3 minutes and 36 seconds just minutes before sunset. Partial eclipse can be seen from parts of the UK on 10th June 2021, 25th October 2022, 8th April 2024 and the 29th March 2025.

We do have a pretty spectacular view, there's only a chink of the Sun's bright light left. But actually, what's surprising me the most is, it's still very bright up here. Look at the light through the window. I mean our telescopes are showing you, because of the special filters, the light of the Sun and there's darkness around it, but it's still surprisingly so bright despite the fact that there's only a tiny slither of the Sun left. And I can tell you, it is the most wonderful thing to experience up here.

We're only seconds away from totality and remember this is only possible because, even though the Sun is 400 times bigger than our Moon, at this moment in our Solar System's history the Moon happens to be 400 times closer to Earth than the Sun and so they appear the same size and the Moon can cover the Sun up completely. We are edging ever closer to totality. I'm looking out for those Bailey's beads, the last chinks of brightness coming through the gaps, left by the Moon's rugged landscape. And of course, then hopefully the diamond ring.

There's no other planet in our Solar System that experiences an eclipse like this one.

Of course, as the Moon continues to edge further away from the Earth, about 3 centimetres each year, in about 500 million years we'll never have a total eclipse again. But look at this, this is Bailey's beads in, I mean, I didn't realise they were going to be so bright. Look at that. It's almost like one ginormous diamond ring left set in a circle of brightness encircling the Moon's shadow. Are we seeing features that look suspiciously like prominences? This is where the chromosphere becomes visible.

(GASPS)

There it is, the diamond ring. And, we have reached totality. We have reached the most incredible moment in a total solar eclipse. There is the corona, the Sun's faint thin atmosphere that you can never see usually, you can only see because the Moon has now completely eclipsed the Sun. There is one tiny feature at about 11 o'clock that looks like a prominence potentially. It could be part of the chromosphere, the inner atmosphere of the Sun. This is extraordinary.

You can see with our closer camera, more features of the chromosphere peeking through the Sun's activity. It's redder in colour because we are closer to the Sun. Look at that! We are definitely seeing prominences here and the beautiful red light of the chromosphere. The layer of the Sun's atmosphere before the corona. I never really thought it was going to be quite this moving - and we are being plunged into darkness.

Eclipse viewing safety

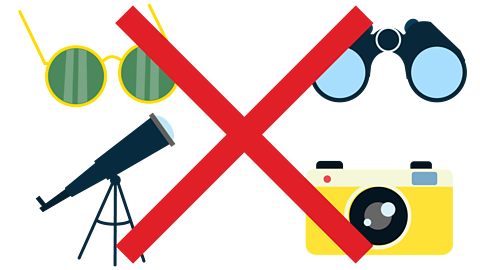

- Never look directly at the Sun: you can damage your eyes forever and even go blind.

- Never look at the Sun through binoculars or a telescope.

- Don't look directly at the Sun through sunglasses, a camera or your phone camera - none of these protect your eyes.

- To watch an eclipse, you will need to wear special glasses, properly darkened and filtered to protect your eyes. You can also safely view the image of an eclipse using a pinhole camera.

Luminous and non-luminous objects

We see something either because it emits its own light, or it reflects light.

An object that gives out, or emits, its own light is called a luminous object.

Examples of luminous objects include:

- the Sun

- stars

- fire

- candle flame

- laser

- light bulb

- luminous mushrooms

- fireflies

- some jellyfish

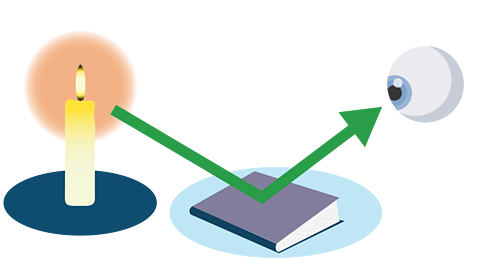

A non-luminous object does not give out its own light. We see it because it reflects the light from a luminous object, like the Sun or a candle, towards our eyes.

The book is a non-luminous object. You see it because it reflects light from the candle flame towards your eyes.

Other examples of non-luminous objects include:

- the Moon

- the planets

- the ground

- a person

- a wall

- a cat

- a whiteboard

Investigating reflection of light

Investigating reflection of light

A mirror reflects light. It is made by putting a thin reflecting layer behind a piece of glass. The reflecting layer is often silver nitrate, held in place by a coat of paint. Most every day mirrors are flat and are called plane mirrors.

In a ray diagram, the mirror is often drawn as a straight line with thick hatchings. The side with the hatchings indicates the non-reflective side.

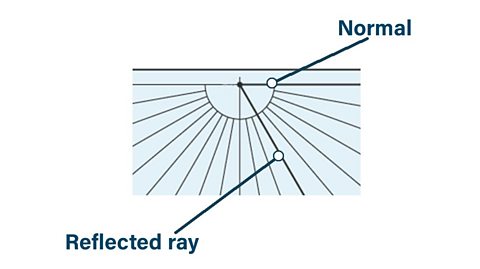

The diagram shows a ray of light reflected from a plane mirror.

Some important new terms:

- The hatched vertical line on the left represents the plane mirror.

- The incident ray is the ray of light going towards the mirror.

- The reflected ray is the ray of light coming away from the mirror.

- The normal is a reference line drawn at right angles to the reflecting surface of the mirror.

- The angle of incidence, i, is the angle between the normal and incident ray.

- The angle of reflection, r, is the angle between the normal and reflected ray.

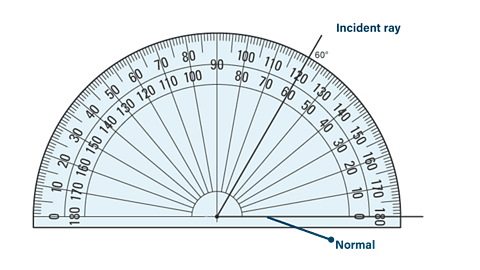

When measuring the angle of incidence, i, or angle of reflection, r, it is important to place the zero line of the protractor along the normal. This will ensure that you measure the angle between the normal and the ray and not the angle between the mirror and the ray.

To investigate reflection from a plane mirror you will need a:

- plane mirror

- ray box

- low voltage power pack with a single slit comb

- sheet of white paper

- protractor

- 30 cm ruler

- sharp pencil

- On a sheet of white paper draw a pencil line – label this AB.

- Using a protractor, draw a normal at C, roughly the middle of AB.

- Draw a line at 20° to the normal.

- Position a plane mirror carefully along AB.

- Direct a single ray of light from a ray box along the 20° line – this is the incident ray. Record the angle of incidence i in a suitable table.

- Draw 2 pencil Xs to mark the position of the reflected ray.

- Take away the mirror and join these Xs back to C. This is the reflected ray. Put an arrow on it to show its direction away from the mirror.

- Measure the angle between the normal and the reflected ray with the protractor and record the angle of reflection r in the table. Make sure that the normal goes through the zero of the protractor.

- Repeat the experiment for a series of incident rays.

Risks/Hazards

| Hazard | Consequence | Control measures |

|---|---|---|

| Ray box gets hot | Minor burns | Do not touch bulb and allow time to cool before handling the ray box |

| Semi-dark room | Increased trip hazard | Ensure working area is clear of trip hazards |

Analysis

Compare the angle of incidence with the angle of reflection for each pair of readings.

Conclusion

It should be clear from your readings that when light is reflected from a plane mirror:

the angle of incidence, i = the angle of reflection, r

This is known as the law of reflection.

For example:

The angle of reflection is 30° if the angle of incidence is 30°.

The angle of reflection is 75° if the angle of incidence is 75°.

The angle of reflection is 0° if the angle of incidence is 0°.

In the third example, if a light ray travelling along the normal hits a mirror, it is reflected straight back along the normal, the way it came.

i = r

If a light ray hits the mirror with an angle of incidence of 45°, it will be reflected with an angle of reflection of 45°.

Specular reflection

Specular reflection

Reflection from a smooth, flat surface is called specular reflection.

This reflection obeys the law of reflection and is the type that happens with a flat mirror.

Properties of the image in a plane mirror

When an object is placed in front of a plane mirror an image is formed.

The image in a plane mirror is:

- upright – but left and right are reversed. We say that the image is laterally inverted

- the same height as the object

- as far behind the mirror as the object is in front

- virtual

A virtual image is an image from which rays of light appear to diverge, and do not actually pass through. A virtual image cannot be formed on a screen.

Notice that the ‘real’ rays, the ones leaving the object and the mirror, are shown as solid lines. The ‘virtual’ rays, the ones that appear to come from the image behind the mirror, are shown as dashed lines. Remember that each incident ray will obey the law of reflection.

Diffuse reflection

If a surface is rough, diffuse reflection happens. Instead of forming an image, the reflected light is scattered in all directions.

This may cause a distorted image of the object, as occurs with rippling water, or no image at all. Each individual reflection still obeys the law of reflection, but the different parts of the rough surface are at different angles and so the reflected rays are not parallel.

Question

What is the angle of reflection?

- The angle of incidence, i = 35°

- i = r and so the angle of reflection, r = 35°

Question

What is the angle of incidence?

- The angle of reflection, r = 32°

- i = r and so the angle of incidence, i = 32°

Question

What is the angle of reflection? (Be careful with this one…)

- The angle between the incident ray and the mirror = 52°

- So, the angle of incidence, i = 90° - 52° = 38°

- i = r and so the angle of reflection, r = 38°

Question

What is the angle of reflection from the second mirror?

- The angle of incidence at mirror A = 70°.

- i = r and so the angle of reflection at mirror A = 70°.

- The angle between the reflected ray and mirror A = 20° (as shown in green in the diagram). As this ray and the two mirrors make a triangle (as highlighted in red on the diagram), the angle between the ray and mirror B = 70° (as shown in purple on the diagram). We know this because the angles within a triangle add up to 180°. If two of the angles are 20° and 90°, the third must be 70°. This means that the angle of incidence at mirror B is equal to 20°.

- i = r and so the angle of reflection at mirror B = 20°.

The periscope

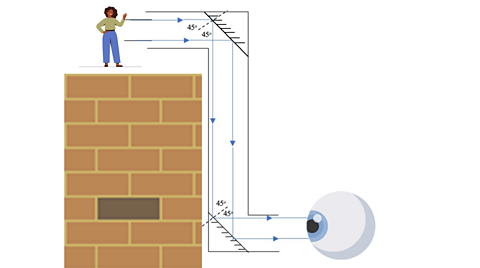

A periscope uses two mirrors to allow someone to look over an obstacle.

- Submarines use periscopes to see ships on the surface of the sea.

- Someone at the back of the crowd at a golf tournament or royal event might use one to see over the heads of those in front.

- The two mirrors are arranged at 45° as shown in the diagram.

- The angle of incidence at the first mirror is 45° and so the angle of reflection is 45°. The rays of light turn through a right angle.

- The same thing happens when the light hits the 2nd mirror, and the rays of light are again turned through 90°.

- The rays emerge parallel to the way they entered the periscope, and the image is upright.

Refraction of light

When light travels from air into glass it slows down because glass is more dense than air.

This change in speed can cause the light to bend at the boundary between the air and glass.

The change in direction of a beam of light as it travels from one material to another is called refraction.

The diagram shows refraction of light passing into, and then out of, a glass block. The same would happen for a Perspex block or for water.

Some important new terms:

Incident ray: the ray travelling towards the glass block.

Refracted ray: the ray inside the glass block.

Emergent ray: the ray travelling away from the glass block on the other side.

The normal is a reference line drawn at right angles to the surface of the glass block.

Angle of incidence i = angle between the incident ray and the normal.

Angle of refraction r = angle between the refracted ray and the normal.

Remember: Angles of incidence and refraction are always measured between the normal and the ray of light. Make sure that the normal goes through the zero of the protractor.

Investigating refraction

Apparatus

- low voltage power pack

- 12V ray box with a single slit comb

- rectangular glass block

- sheet of white paper

- protractor

- sharp pencil

Method.

- Place the rectangular glass block on a sheet of white paper and draw around it carefully with a pencil.

- Remove the glass block. Use the protractor to draw a normal approximately 1/3 of the way along the longest side.

- Use a protractor to measure angles of incidence from this normal of 10°, 20°, 30°, 40°, 50°, 60° and 70°. Draw in the incident rays corresponding to these angles and label them A, B, C… Record these angles of incidence in a suitable table.

- Carefully replace the block on the outline. Direct a narrow ray of light along the line marked A. This is the incident ray for the angle of incidence, i = 100.

- With the pencil mark two Xs to indicate the direction of the emergent ray. Mark the Xs as far apart as possible.

- Remove the block again. Join the Xs with a pencil line, drawn using a ruler. Extend this line back to the block. This is the emergent ray: label it 'A'.

- Use the ruler to join the incident and emergent rays together with a pencil line. This is the refracted ray. Carefully mark in the angle of refraction, r, between the refracted ray and the normal.

- Measure the angle of refraction with a protractor and record in the table.

- Measure the angle of emergence, e, with a protractor and record in the table.

- Repeat the procedure for each of the incident rays, recording angle of refraction and angle of emergence in the table.

Risks

| Hazard | Consequence | Control measures |

|---|---|---|

| Ray box gets hot | Minor burns | Do not touch bulb, allow time for ray box to cool before handling |

| Semi-dark environment | Increased trip hazard | Ensure work space is clear of trip hazards before lowering lights |

Analysis

Compare the size of the angle of refraction, r, with the angle of incidence, i.Compare the size of the angle of emergence, e, with the angle of refraction, r.

Conclusion

The angle of refraction is less than the angle of incidence. Therefore, when light travels from air into glass it bends towards the normal.

The angle of emergence is greater than the angle of refraction. Therefore, when light travels from glass into air it bends away from the normal.

Direction of refraction

Glass is denser than air, so when light passes from air into glass it slows down.

- The ray is bent towards the normal.

Light speeds up as it passes from glass into air because air is less dense than glass.

- The ray is bent away from the normal.

The greater the change of speed of light at a boundary, the greater the refraction. Light is bent more by glass than by water because glass is denser than water and so slows it down more.

One way of remembering the direction of refraction is to use the word FAST.

- If light gets Faster it bends Away from the normal.

- If light gets Slower it bends Towards the normal.

| Letter | Meaning | When this happens | Example |

|---|---|---|---|

| F | Faster | Dense to less dense | Glass to air or Water to air |

| A | Away | ||

| S | Slower | Less dense to dense | Air to glass or air to water |

| T | Towards |

If light is incident along the normal when it passes from air into glass it still slows down but its direction does not change – it passes straight through.

Likewise, if light is incident along the normal when it passes from glass into air it still speeds up but its direction does not change – it passes straight through.

Refraction explains why an object appears to bend when it goes through water.

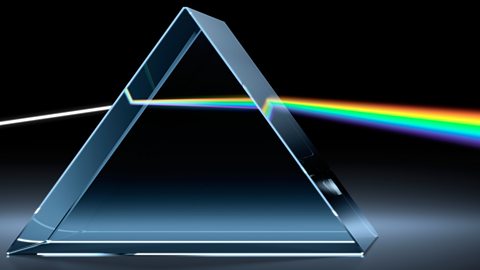

Refraction by a prism

The incident ray is refracted towards the normal as it enters the glass prism from air.

It is then refracted away from the normal at the boundary between glass and air as it leaves the prism.

A photographer explains the science of colour.

Light is incredibly fundamental to the practice of photography, and without it, we're not actually able to make any images.

My name's Tom Harrison, I'm a photographer and I use photography in my artistic work.

Visible light is just one part of the electromagnetic spectrum. Colour sits within that spectrum, and the frequency of the colour determines its actual colour.

We have the low frequency with red and yellow, and then as you go up the spectrum to the more high frequency colours, we have green, and then blue and then violet at the top end.

Everyone's perception of colour is different. So if you were to look at a red strawberry, your perception of that colour red could be fundamentally different to another person.

All colour that we perceive, essentially, is made up of red, green and blue light. We can mix those together to produce every single possible shade of colour within the spectrum.

The way that light interacts with the world actually defines how we see things. Materials that absorb light appear appreciably darker than materials that reflect light.

When we're talking about digital cameras, we're talking about the way that they actually perceive light themselves. And the model that they use is very similar to the human eye in so far as they're sensitive to red, green, and blue light.

This appreciation of the way that colour and light behaves is really integral to actually producing a photographic image.

If we want to light a subject, we really need to know how that light behaves in order to create the image that we're hoping for.

When white light passes through a prism it can be split up into its colours. The band of colours seen is called the spectrum of white light.

The spectrum is produced because different colours of light travel at different speeds in glass.This means that each colour of light is refracted by a different amount when it enters the glass and when it leaves.

- Red light is slowed down least by glass and is refracted least.

- Violet light is slowed down most by glass and is refracted most.

The splitting of white light into its colours in this way is called dispersion.

Here are the seven colours of the spectrum listed in order of their frequency, from the lowest frequency to the highest frequency:

- red

- orange

- yellow

- green

- blue

- indigo

- violet

One way to remember the order: ‘Richard Of York Gave Battle In Vain’.These are the same colours seen in a rainbow. A rainbow is formed when sunlight shines through water. The tiny water droplets act as prisms, refracting each colour of the white light by a different amount, to produce the spectrum of light arched across the sky.

Professor Brian Cox explains how white light disperses into different colours.

The white light of the sun is made up of all the colours of the rainbow.

And when it reaches the Earth, those individual colours are revealed.

Photons from the sun rain down and enter water droplets. They reflect off the rear face, come out of the front again and into your eye. But the blue photons, the higher-energy ones, behave differently to the green ones and the yellow ones and the red ones. They come out at a shallower angle, and that's why you get the full spectrum of colours from the white light of the sun.

And it's this light that paints the Earth.

Test yourself

Try your hand at putting colours in order of low to high frequency with this quick quiz.

Test your knowledge of light waves with this pop quiz!

More on Physics

Find out more by working through a topic

- count3 of 8

- count4 of 8

- count5 of 8

- count6 of 8