Key points

- There is a long history of Black people living in Britain - dating back to Roman Britain, at least. However, after 1945 the migration of Black people from the Caribbean colonies in the British Empire and the wider CommonwealthThe Commonwealth was set up in 1926 between Britain and all partly independent countries in the empire, which were also known as dominion states. Eventually other territories within the empire became part of the Commonwealth. increased significantly.

- The 1948 Nationality Act gave Commonwealth citizenship to everyone in the British Empire. This meant people from across the Empire were entitled to live and work in Britain.

- Many Black people from islands in the Caribbean regarded Britain as their mother country and moved to Britain. However, after arriving many experienced hostility, discrimination, abuse, and violence.

- Black people spoke out and protested against racism. This activism led to Britain’s first Race Relations laws being passed in the late 1960s which made discrimination based on colour, race, ethnic or national origin illegal.

The Windrush

- Black people who came to live in Britain between roughly 1948 - 1971 came to be known as the Windrush Generation.

- Despite opposition from people in the government to migration from islands in the Caribbean, many Black people decided to take up job opportunities in Britain.

- In June 1948, the Empire Windrush ship arrived in England from Jamaica. According to the ship’s passenger lists, 802 passengers gave their last country of residence as being somewhere in the Caribbean.

Lord Kitchener, the Trinidadian calypso artist was one of the passengers. He performed his song ‘London Is The Place For Me’ live for news cameras at the dock. He sang “I am glad to know my mother country”. Many passengers thought of Britain as their ‘mother country’ and believed they would be welcomed.

To find out more about the experiences of the Windrush generation and the cultural impact of the Windrush generation visit this KS3 History article - Caribbean migration: the Windrush generation.

Immigration and post-war labour shortages

After World War Two, Britain had a severe shortage of workers. In 1946, a government report said that the country needed over a million extra workers. British business and organisations had to find ways to attract more people to migrate to Britain to meet the need for more workers.

Later, the 1948 Nationality Act granted everyone in the British Empire CommonwealthThe Commonwealth was set up in 1926 between Britain and all partly independent countries in the empire, which were also known as dominion states. Eventually other territories within the empire became part of the Commonwealth. citizenship - people from across the Empire were entitled to live and work in Britain. Organisations such as London Transport ran direct recruitment drives in the Caribbean Islands and gave out job offers. However, most of the people who arrived in Britain at this time hoping to work didn’t have direct job offers, but came knowing there were jobs available because of the large number of job adverts in British newspapers that were sold in their home countries.

Some businesses were happy to have workers from the Caribbean filling their job vacancies. However, some politicians preferred for jobs to be taken by white workers from Europe - under the European Voluntary Workers scheme (EVW). Some MPs wrote to the Prime Minister Clement Atlee to call for a halt to what they saw as an ‘influx’ of Caribbean people from the British Empire from coming to Britain. This was driven by the racist attitudes of those within the government.

There were several attempts by the Ministry of LabourA British government department that had dealt with issues and activities related to employment. to limit or stop Black citizens of the Empire from moving to Britain. The government tried to stop the Empire Windrush ship from leaving Jamaica in 1948. When this failed, the Prime Minister Clement Atlee made enquiries to see if the Windrush passengers could be sent to East Africa and given work there instead. The Minister of Labour, George Isaacs showed his opposition by saying he hoped “no encouragement would be given to others to follow their example”.

A hostile reception

Racism meant that many Black people were not always welcomed. More significance was given to skin colour rather than their legal status as British citizens and contribution to Britain’s past and future.

Racism was shown in many ways and in many areas of life, including:

- Housing - Some property owners refused to rent their properties to Black people. This limited the places they could live in and made them vulnerable to landlords who charged unfairly high rents.

- Jobs - A colour barWhen equal employment opportunities in a particular industry or organisation are denied to members of ethnic minorities. kept Black people out of certain workplaces. Where they were employed, they were less likely to be given positions of authority and they were more likely to be found in lower-paid and insecure roles.

- Hatred - Open racial hostility could be felt by Black people being called offensive slurs. ‘Keep Britain White’ (KBW) became a popular slogan used by racist groups like the White Defence LeagueA British far-right political party. and some political leaders.

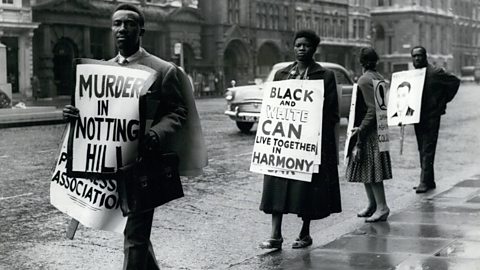

Racial violence in Nottingham and Notting Hill - 1958

In the summer of 1958, racial tensions erupted in violence against Black communities in both Nottingham in the East Midlands and Notting Hill in London. There was open hostility from young white working class people against the growing Black community. Teddy Boys were groups of young white people who wore EdwardianSomething related to the period between 1900 - 1914 during most of the reign of King Edward VII. style suits. Some formed gangs and had violent clashes with each other. Some also attacked immigrants and held racist views. Much of the violence in Notting Hill and Nottingham was led by the Teddy Boys.

Tensions were also inflamed by fascist leaders such as Oswald Mosley who held meetings and urged the local community to ‘Keep Britain White’. Lack of employment opportunities and poor housing also created friction, which increased hostility towards Black people in these areas.

In both Nottingham and Notting Hill, the violence was sparked by people who also particularly hated Black men and white women having interracial relationships. In Nottingham, a Black man was assaulted - this led to further violent clashes against Black people in the St. Anne’s area. A hostile crowd of over a thousand people gathered. Eight people had to be taken to hospital. A week later in Notting Hill, around 400 mainly young, white men attacked Black people with weapons and attacked their homes with petrol bombs. After two nights of attacks, in Notting Hill Black people from across the city came to defend and protect the local community. The violence lasted almost two weeks. More than 140 people were arrested.

The murder of Kelso Cochrane - 1959

Kelso Cochrane was a 32-year-old man who was born in AntiguaAn island in the Caribbean Sea.. On the night of May 17, 1959, Kelso was walking home in Notting Hill, London. A gang of young white men attacked and killed him. They fled the scene of the crime. Two men were arrested but were later released without any charges.

The police detective who led the investigation insisted that the white teenagers were motivated by robbery, not racism. However, Notting Hill was a key area where the White Defence LeagueA British far-right political party. and Oswald Mosely’s fascist operated. There had also been two weeks of racial violence in 1958. Racial tensions and violence were clearly present in Notting Hill.

The response of the Black community

The murder of Kelso Cochrane angered many people in the Black community and motivated more campaigning against racial injustice in Britain. In June 1959, Black protestors from the Coloured People's Progressive Association (CPPA) marched in WhitehallThe area in London where the Parliament is based. against racial violence and racism in Britain.

Claudia Jones was a skilled political organiser who brought people together to fight for the interests of their community. She worked with the CPPA and other groups to form the Inter-racial Friendship Co-ordinating Council. They organised a memorial meeting for Kelso Cochrane and a public funeral which was attended by over a thousand people. They also sent a letter to the Prime Minister asking for more protection for Black people against racial violence.

Claudia Jones was born in Trinidad, she became the editor of the West Indian Gazette, a newspaper which served the interests of West Indians. She also played a crucial role in organising the first London Carnival held in St Pancras Town Hall.

How did the Notting Hill Carnival develop?

- The first outdoor Carnival was held in Notting Hill in 1966. A local resident and social worker, Rhaune Laslet, organised the event for local children.

- The carnival in Notting Hill was seen as a positive way to bring the different communities in the area together - through the celebration of Caribbean culture, music and heritage.

- The Notting Hill Carnival is still a community-led event and is celebrated every year in August. It is enjoyed by more than a million visitors and is one of the largest street events in Europe.

1962 Commonwealth Immigrants Act

While there was strong disapproval of the violence against Black people, there was still a strong antipathyA strong feeling of dislike. towards Black immigrants. Anti-immigration began to dominate public conversation and politics. Groups like the White Defence LeagueA British far-right political party. called for Black people to be repatriateTo send someone back to the country of their birth or connection. and immigration from the CommonwealthThe Commonwealth was set up in 1926 between Britain and all partly independent countries in the empire, which were also known as dominion states. Eventually other territories within the empire became part of the Commonwealth. to be stopped.

Many politicians believed the solution to racism was immigration control, rather than dealing with the problem of racism itself. The 1962 Commonwealth Immigrants Act restricted the immigration of Commonwealth citizens to Britain. It was condemned by Black activistA person who campaigns to bring change. such as Claudia Jones, and some politicians such as Hugh Gaitskell the Labour Party leader of the oppositionThe member of Parliament that leads the MPs who are not part of the ruling party and government.. Gaitskell called the act “cruel and brutal anti-colour legislation”.

The Bristol Bus Boycott -1963

Many Black activistA person who campaigns to bring change. in Britain made connections between their struggles and those faced by African Americans in the United States. They also drew inspiration from tactics, like boycottA refusal to buy goods or services from a person or organisation as a form of punishment or protest., used by US civil rights activists against racial injustice.

Before 1965, racial discrimination was legal in Britain. In Bristol, there were approximately 3,000 Black migrants who lived in the city. They faced discrimination in areas such as housing and employment. The company that ran Bristol’s bus service - the Bristol Omnibus Company - operated under a colour barWhen equal employment opportunities in a particular industry or organisation are denied to members of ethnic minorities. which banned anyone who was not white from working as a bus driver or conductor.

An activist organisation called the West Indian Development Council (WIDC) was set up by local black leaders such as Roy Hackett. The leaders joined forces with Bristol’s first Black Youth Officer, Paul Stephenson who became the group’s spokesperson.

To highlight and challenge the bus company’s racist policy, Stephenson encouraged Guy Reid-Bailey who was well-qualified for the role of bus conductorA person who collects fares and sells tickets on a bus. to apply for a job at the Bristol bus service. Reid-Bailey was not given an interview because the company realised that he was Black.

In April 1963, Stephenson and the WIDC called for a boycott of Bristol’s buses. Some students and staff from Bristol University also held a demonstration in the city centre to support them. Many political leaders from around the country also supported the boycott.

Pressure grew on the bus company to end its colour bar. In August 1963, the Bristol Omnibus Company was forced to end its racist policy.

The first laws against racial discrimination

The successful outcome of the Bristol Bus Boycott did not mean that racial tensions in Bristol or Britain faded away. But it did bring more attention to racial inequality and put pressure on the government to respond to racism in Britain.

As a result, two new laws were passed.

- The 1965 Race Relations Act made racial discrimination in public places and the promotion of racial hatred an illegal offence.

- The 1968 Race Relations Act made it illegal to refuse housing, employment, or public services to someone on the grounds of their colour, race or ethnic or national origins.

Test your knowledge

Solve the Story!

An exciting new series from the Other Side of the Story, designed to help young people strengthen their media literacy skills.

More on The struggles against racism and for human rights

Find out more by working through a topic

- count2 of 2