Dan Snow:Hello, I'm Dan Snow.

Dan Snow:Looking into the Great War, one of the myths you encounter is that the British upper classes dodged the worst of it.

Dan Snow:They were the generals who planned attacks from the safety of a war room and whose incompetence sent thousands of working class soldiers to their deaths.

Dan Snow:Well that's not an accurate portrayal of how things were. Seventeen percent of the officers who fought in the conflict would be killed. For ordinary soldiers the number was 12%.

Dan Snow:Although it seems almost wrong to say it, for some of Britain's working class, for as long as they could survive, the war brought some of the best conditions and changes in their circumstances that they'd ever known.

Dan Snow:Let's join Jeremy Paxman to find out how that could possibly be the case.

Jeremy Paxman:The war took a heavy toll on the upper classes. Many of their sons were quick to volunteer. As officers they were expected to lead from the front. As a result they were five times as likely to die as an ordinary Tommy.

Jeremy Paxman:There were times in the war when the life expectancy of a lieutenant was said to be six weeks.

Jeremy Paxman:The death of Tommy Agar-Robartes seemed to break the family's spirit. It signalled the end of this great estate which shrank to a fraction of its former size.

Jeremy Paxman:Ancient families crippled by death duties and with a son who might have inherited killed in the war found themselves forced to sell up.

Jeremy Paxman:By the end of 1919 it was reckoned that over a million acres of England and Wales had gone under the hammer. It was a sort of revolution.

Jeremy Paxman:The sell-off brought to an end the almost feudal power of the landed gentry. But if the war created some unexpected losers, there were also some unexpected winners.

Jeremy Paxman:The people who did best were the poor. Especially the very poor.

Jeremy Paxman:The writer Robert Roberts grew up in a corner shop in a typical Salford slum. He saw first-hand how the very poor lived, or tried to live.

1500:02:37:14 00:02:50:23Jeremy Paxman:To eat, bread with a scrape of margarine or jam or dripping. If it was a special occasion perhaps a pot of tea. But hardly ever any eggs, any milk or any meat.

Jeremy Paxman:To live, three damp rooms for a family of eight, with children sleeping four to a bed. Hardly surprising then that the mortality rate among the children was one in four. That was twice what it wasamong soldiers at the front.

Jeremy Paxman:No wonder so many of them failed their army medical when they tried to join up.

Jeremy Paxman:Those that did enlist were delighted to find it meant a full stomach. "Meat every day", they said, just as the recruiting sergeants had promised.

Jeremy Paxman:When they came back from the war they were fitter, broader and stronger than when they'd left.

Jeremy Paxman:Robert Roberts called The Great War "the great release". Because quite apart from the demands of the army, there was a need for masses of labour. And that meant that those who had previously been part-timers or casual labourers or unemployed could suddenly earn good money and feed themselves.

Jeremy Paxman:Across the counter of his parents' shop, Roberts noted that, for the first time ever, the customers had money in their pockets all week. His respectable shopkeeper parents were appalled at the new wealth these people were enjoying.

Jeremy Paxman:Robert Roberts' father described how, just how before Christmas, a well-paid young woman from one of the local munitions factories came into his corner shop and asked him why he hadn't got "sommat worth chewin'".

Jeremy Paxman:He was pretty annoyed and he asked her what she meant and she said, "Well, tins of lobster or some of them big jars of pickled gherkins."

Jeremy Paxman:Britain was beginning to look like a different country. Full employment had pushed up living standards. Fewer babies were dying. Men and women lived longer. Curbs on drink had cut drunkenness and domestic violence. A third of all workers had joined a union.

Jeremy Paxman:And to repay its debt to the people of Britain, the government had given all men and some women the right to vote.

Jeremy Paxman:The anti-war labour MP, Ramsay MacDonald, decided that the demands of the war had done more for social reform than all the political campaigns before it.

Video summary

Jeremy Paxman challenges the stereotypical view that officers and generals were not as badly affected by the war, showing they were 5 times more likely to die than a soldier.

He looks at examples of families who were devastated by the impact of the war, with land being sold off to pay death duties and changing the amount of power in the hands of wealthy land owners.

Some of the poorest in society found life improved after the war, with an increase in employment opportunities leading to higher incomes and consequently better diets.

Infant mortality fell, life expectancy was rising, and some women were given the right to vote for the first time.

Teacher Notes

Key Stage 4 / GCSE:

Could be used in a lesson looking at social change after World War One.

Students could be asked to predict what they think the impact of the War would have been on working and upper-class families.

Then they could watch the clip and discuss if anything surprises them or if there is anything they disagree with.

This clip will be relevant for teaching History at KS4/GCSE in England Wales and Northern Ireland.

Also at National 4/National 5 and Higher in Scotland.

How challenging was the life of a pilot in World War One? video

James May looks at the dangers and challenges facing pilots in World War One.

What were trench conditions like in World War One? video

Saul David looks at how British soldiers coped with trench conditions in World War One

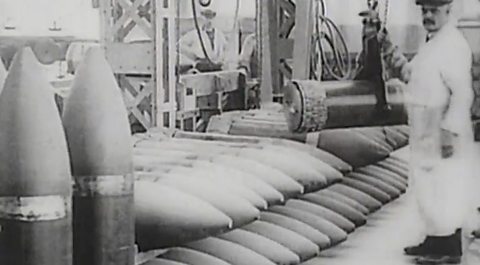

How did Britain meet demands for weapon production in World War One? video

Saul David on how Britain struggled to produce the weapons to supply the army in World War One.