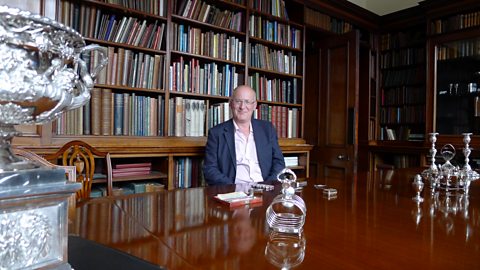

Professor Jeremy Black:

For me there was one entrepreneur, above all others, who understood the opportunities presented by the growing consumer market of the industrial revolution - Josiah Wedgwood.

He was brought up in a family of potters in north Staffordshire, and inheriting only £20 from his father. But his genius for creating - and then satisfying - customer demand made him one of the richest men in the country.

Wedgwood appreciated that the middle classes could not be relied on to understand that they actually necessarily wanted these new-fangled goods being manufactured across Britain.

Therefore he had to persuade them to buy them, indeed to desire them, in their households. And to that end he became the father of what we today call advertising and marketing.

For centuries most families’ household goods were made by local artisans and bought at local markets.

By the start of the 18th century shops were beginning to be open in London and large cities. But Wedgwood, working with his marketing guru Thomas Bentley, unveiled a new concept.

They opened the first purpose-built show room in London’s fashionable West End in 1774.

Wedgwood and Bentley understood that women would be the prime purchasers for their ceramic wares and to that end in their showroom in Greek Street in London they had a grand parlour in which the customers would be greeted and would meet and chat.

And then they would be taken round the showroom, to see the great new products which were coming through the factories.

Wedgwood led the way in the shopping revolution.

But for true success, Wedgwood realised his pottery needed to be of a consistently high standard and to be known beyond his London showroom.

His break occurred in 1765 when Deborah Chetwynd lady in waiting to Queen Charlotte, and a member of the Staffordshire aristocracy asked among the Staffordshire potters who could make a tea service for the queen. It involved a new technique, rebinding gold gilt to glaze

He believed if he could win the Queen’s patronage for his wares, then all society would follow. So he spent months experimenting with different methods of gilding until he was satisfied.

The Queen ordered a set and it became known as Queen’s ware, one of Wedgewood’s most successful products.

Wedgwood understood how to appeal to the social aspirations of the middle classes. Now they too could drink from the same china as the Queen.

Wedgwood’s genius was to understand the power of marketing. He was instrumental in dreaming up a wealth of ground-breaking techniques and ideas, many of which are still used today.

Video summary

Professor Jeremy Black places one figure, Josiah Wedgwood, above all others as a hero of the Industrial Revolution.

From relatively humble beginnings he built up a business empire by creating and then meeting customer demand.

While he certainly made pottery in his factories, his real genius lay in making people want this pottery – getting them to see his goods as desirable must-haves, just like today’s designer brands.

It was Wedgwood who pioneered the idea of a showroom where he could meet and chat to his customers and, instead of loading them up in the shop, he could encourage them to order from his mail order catalogue.

Perhaps his greatest triumph was in exploiting the fact that he had made a tea service for the Queen.

If his wares were good enough for royalty then a marketing genius like Wedgwood could make everybody else want their teacups from the same maker.

This short film is from the BBC series, Why the Industrial Revolution Happened Here.

Teacher Notes

This short film could be used to consider the historical significance of 18th and 19th century entrepreneurs, starting with Josiah Wedgewood.

Criteria for significance could include impact made during their lifetime, whether this has been of lasting benefit, whether there is evidence to show they are remembered today, and the extent that their work influenced others both at the time and since.

This short film is suitable for teaching history at Key Stage 3 and GCSE, Third Level and National 4 & 5, in particular units on the Victorians and the Industrial Revolution.

The brains behind the Industrial Revolution. video

Professor Jeremy Black shows how, at the birth of the Industrial Revolution, Britain's political and economic climate allowed inventive minds to blossom.

The growth of industry and factory towns in Britain. video

Professor Jeremy Black explains how the invention of factories completely changed the nature of work and made Birmingham one of Britain's largest cities.

The importance of coal in the Industrial Revolution. video

Professor Jeremy Black digs deeper into our industrial past and finds that Britain sat on top of bountiful coal deposits, perfect to power newly-invented steam engines.

The transport revolution: Britain's canal network. video

Canals were the motorways of the 1700s, says Professor Jeremy Black. Building them took huge amounts of money and some incredible feats of engineering.

Why did Britain need a better road network? video

Professor Jeremy Black explains how the state of Britain's roads in the early 1700s was holding back the Industrial Revolution, and how business owners changed all that.