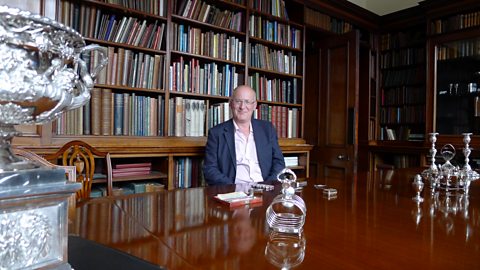

PROFESSOR JEREMY BLACK:'The industrial revolution in the 18th Century had seen unprecedented improvements to Britain's transport network.' But it was next great advance in transport technology

PROFESSOR JEREMY BLACK:that truly enabled Wedgewood and his ilk to expand. The impact is still in the landscape to this day. These were the canals - the motorways of the 18th Century. 'Once again private entrepreneurs lead the way. Wedgewood had noted that the canal, built by James Brindley to bring coal from the Manchester coal fields to the river Mersey'

PROFESSOR JEREMY BLACK:'reduced its cost by half. He thought a canal connecting his pottery's in Stoke-On-Trent could bring clay from the Mersey and flint for glazes from the river Trent. Andrew Watts is a canal historian.'

ANDREW WATTS:To bring in the sort of materials that one canal barge would bring in with one horse and one man, would have taken at least 100 pack horses and mules in the 18th Century.

PROFESSOR JEREMY BLACK:'Wedgewood used his great powers of persuasion to garner the support of the North Staffordshire MP's and peers. And sent a petition to parliament to set up a company to build the Trent and Mersey canal. But there was a problem. The route of the waterway took it through the rolling hills of Staffordshire.'

PROFESSOR JEREMY BLACK:'This difficult terrain demanded that Brindley undertake one of the greatest engineering feats of the time.'

ANDREW WATTS:See you later.

PROFESSOR JEREMY BLACK:'The digging of the Harecastle tunnel, north of Stoke-On-Trent.'

ANDREW WATTS:The tunnel is 2880 yards.

ANDREW WATTS:From one end to the other, so that's well over a mile and a half getting on for two miles. Four times longer than the longest tunnel built anywhere in the world. Up to that point.

PROFESSOR JEREMY BLACK:And how did they build it?

ANDREW WATTS:They built it by hand, picks, shovels and blasting powder. Using very basic surveying equipment, they built it straight.

PROFESSOR JEREMY BLACK:How did they get through it?

ANDREW WATTS:Well, they didn't have an engine, of course.

PROFESSOR JEREMY BLACK:No.

ANDREW WATTS:They had to leg through the tunnel Two men would lie on their backs, on the boards on the boat with their feet on the tunnel wall and they would walk the boat through.

PROFESSOR JEREMY BLACK:Roughly, how long would that have taken?

ANDREW WATTS:That would have taken them about two hours. Very hard work.

PROFESSOR JEREMY BLACK:Yeah.

PROFESSOR JEREMY BLACK:'The Trent and Mersey canal opened in 1777, five years late. But within a few decades narrow boats were carrying over a quarter of a million tonnes of goods annually through the tunnel. By greatly reducing the cost of transporting goods to and from Stoke-On-Trent, the canal helped the potteries'

PROFESSOR JEREMY BLACK:'become one of the great ceramic centres of the world. And in the process made its shareholders, including Josiah Wedgewood, very rich. These canals were built across Britain. Linking coasts and navigable rivers, and transforming the profitability of British industry.'

PROFESSOR JEREMY BLACK:If I had to pick a symbol for the early industrial revolution - it would be the canal. Which dramatically cut the cost of taking raw materials to factories and the finished goods on to market.

Video summary

According to Professor Jeremy Black, canals were the motorways of the 1700s.

As well as supporting turnpike roads, pottery millionaire Josiah Wedgwood also supported the building of canals – they were perfect for transporting his pottery goods.

It took huge amounts of money and some incredible feats of engineering, like the Harecastle Tunnel, but Wedgwood got his canal and it connected his factories to the rest of the country.

In the 1770s canals linked the country, carrying goods cheaply and efficiently. Without them it is hard to see how the Industrial Revolution could have happened.

This short film is from the BBC series, Why the Industrial Revolution Happened Here.

Teacher Notes

This short film could be used as stimulus to prepare your class for a discussion about the significance and importance of the canal system on business and industrial output in Britain during the 19th century.

Ask students to:

(a) Make a list of the advantages and disadvantages of canal transport.

(b) Use primary testimony to examine the consequences of technological change on populations.

© Understand the reasons why freight carrying on the canals declined in the 19th and 20th centuries.

As an extension, ask students to examine the reasons why canal transport may represent a positive option for the carrying of certain types of freight in the 21st century.

This short film is suitable for teaching history at Key Stage 3 and GCSE, Third Level and National 4 & 5, in particular units on the Victorians and the Industrial Revolution.

Josiah Wedgwood: Genius of the Industrial Revolution. video

Professor Jeremy Black explores Josiah Wedgwood's innovative ways of marketing and advertising his pottery, including opening the first ever showroom.

The brains behind the Industrial Revolution. video

Professor Jeremy Black shows how, at the birth of the Industrial Revolution, Britain's political and economic climate allowed inventive minds to blossom.

The growth of industry and factory towns in Britain. video

Professor Jeremy Black explains how the invention of factories completely changed the nature of work and made Birmingham one of Britain's largest cities.

The importance of coal in the Industrial Revolution. video

Professor Jeremy Black digs deeper into our industrial past and finds that Britain sat on top of bountiful coal deposits, perfect to power newly-invented steam engines.

Why did Britain need a better road network? video

Professor Jeremy Black explains how the state of Britain's roads in the early 1700s was holding back the Industrial Revolution, and how business owners changed all that.