Who is David Attenborough?

Sir David Attenborough has inspired millions by bringing the natural world into our homes and classrooms.

Thanks to a life marked by a tenacious desire to explore, innovate and enlighten, his impact is even more surprising than you might expect.

The writer, broadcaster and naturalist, Sir David Attenborough was born on 8 May 1926. He was educated at Clare College, Cambridge and after working at an educational publishing house, started working as a trainee at the BBC in 1952. As controller of BBC Two, he oversaw the first ever colour broadcasts in Europe.

We recognise him as the voice of natural history programmes for the past 70 years. He has brought the natural world into our living rooms and classrooms through award-winning natural history programs such as Life on Earth, The Private Life of Plants and The Blue Planet. With over 40 animals and plant species named after him, and a constellation, he has explored uncharted land and met the remotest people on Earth, inspiring viewers with an interest in the natural world.

We look back at some of the incredible ways Sir David has helped shape our lives and understanding of the natural world.

Nine fascinating ways David Attenborough has shaped your world

1. 1954 - Wildlife for the masses

Sir David Attenborough joined the BBC as a trainee in 1952, having only ever watched one television programme.

His early career included the high octane round-table debate, Animal, Vegetable, Mineral? But the tenacious 28-year-old was seeking new ways to make films and a life outside the television studio. The result was the hit series 'Zoo Quest,' which combined live studio presentation with footage shot on location for the first time. It brought rare animals - including chimpanzees, pythons and birds of paradise - into viewers' living rooms and proved wildlife programmes could attract big audiences.

Attenborough uses his shirt to catch a crocodile in the Borneo swamps. (Zoo Quest, 1956)

Everyone had told us that the river was infested with man-eating crocodiles, but it wasn’t until one morning, three weeks after our arrival in Borneo, when I was looking for frogs that were whistling and chirping in the swamps fringing the river bank, that I actually saw one.

And it was no ordinary one either, but the variety with the long, thin nose, a gavial.

But as you can see, no one could class this little baby as a man-eater, even though he had got quite a bite.

2. 1965 - Civilisation – in colour!

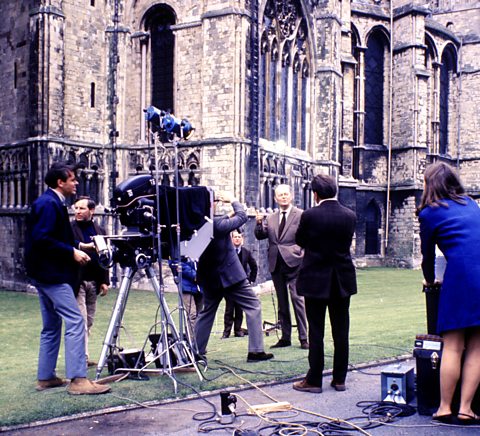

We can't attribute Western civilisation to Attenborough, but we can give him the credit for one of its greatest achievements: colour television.

As Controller of BBC Two, he oversaw the first ever colour broadcasts in Europe, rushing to beat rival German broadcasters by three weeks. He then commissioned the critically-acclaimed series Civilisation, written and presented by art historian Kenneth Clark. The Ascent of Man, presented by humanist scientist Jacob Bronowski, soon followed. These landmark series helped inaugurate a new kind of television documentary, putting history, culture and science on screen in ways never seen before.

3. 1969 - Monty Python's Flying Circus

By now BBC Director of Programmes, Attenborough continued to innovate and reinvent television – but this time in the world of comedy.

He commissioned Monty Python's Flying Circus, a cult sketch show which made stars out of John Cleese, Michael Palin, Terry Jones, Eric Idle, Graham Chapman and Terry Gilliam. The show was a global phenomenon, inspiring generations of comedians around the world. In Britain, Python became part of the nation's cultural DNA, encapsulating a recognisably British eccentricity and spawning popular catchphrases and figures of speech.

4. 1975 - Back to nature

Long before Bear Grylls slept in a camel carcass, Sir David was trekking through uncharted wilderness to film some of the remotest people on earth.

Freed from his role as a BBC executive, Attenborough went back to nature to become an explorer. He made a series of programmes about tribes, some so isolated it's thought they hadn't been contacted by Europeans before Sir David's arrival. He immersed himself in their cultures, wearing nothing but a loin cloth while filming in the Solomon Islands. In showing us ways of life so different from our own, Sir David helped us understand both the diversity and universality of the human experience.

On an expedition in New Guinea, Attenborough's crew give gifts to the Biami tribe. (A Blank on the Map, 1971)

One of the most popular gifts in the remoter parts of New Guinea is newspaper. It is used for smoking the raw, powerful tobacco that every village grows. Some people will carry a load for a day for a couple of sheets or so, but these people normally use dried leaves as cigarette wrapping and had no idea what to do with the paper. They took it rather as though it was some sort of useless memento. This plainly was not a success, so Laurie tried salt instead. This was much better received. And what with that and cigarettes made for them from newspaper by the police, all looked well.

The Biami tribe speaking amongst themselves.

After about an hour when they started to leave, they seemed to be as delighted by the meeting as we were ourselves.

5. 1979 - Inventing epics

Now a staple of any self-respecting Brit’s television diet, Sir David helped invent the natural history documentary as we know it today.

In the late 1970s, he took inspiration from series like Civilisation and The Ascent of Man and travelled the globe to deliver his definitive take on the wonders of the natural world. A natural history programme of this scale and ambition had never been attempted before. The result was Life on Earth, a televisual feast which used stunning photography and innovative camera techniques to show animals in their natural habitats. It’s estimated that 500 million people watched the series worldwide.

One of the most memorable moments of television history, Attenborough encounters rare mountain gorillas. (Life on Earth, 1979)

There’s one ape, however, that spends nearly all its time on the ground. It lives here 10,000 feet up on the flanks of the volcanoes of Central Africa, on the borders of Rwanda and Zaire. It’s the biggest of all the apes, the shyest, one of the rarest, and until recently, one of the least known – the gorilla.

The group of gorillas that lives here has been studied by scientists for several years and has become sufficiently accustomed to human beings to allow you to approach quite close. But you have to behave properly and you mustn’t conceal yourself too well. If you suddenly appeared close to them, and took them by surprise, then they would almost certainly charge. There’s a look out sitting on that tree and he’s already seen me.

There is more meaning and mutual understanding in exchanging a glance of the gorilla than any other animal I know. We’re so similar. Their sight, their hearing, their sense of smell – they’re so similar to ours that we see the world in the same way as they do. They live in the same sort of social groups. Permanent family relationships. They walk around on the ground as we do, though they’re immensely more powerful than we are, and so, if ever there was a possibility of escaping the human condition and living imaginatively in another creature’s world, it must be with the gorilla. And yet as I sit here, surrounded by this trusting gorilla family, they’re gentle, placid creatures, the boss of the group is that silverbacked male. The rest are adult females with their young sons and daughters. And this is how they spend most of their time, lounging on the ground, grooming one another.The male is an enormously powerful creature but he only uses his strength when he is actually protecting his own family from a marauding male from another group and it’s very, very rare that there is any violence within the group, so it seems really, very unfair that man should have chosen the gorilla to symbolise all that is aggressive and violent when that’s the one thing that the gorilla is not and that we are.

That grasping, manipulative hand has now become something more – an instrument with which to explore and investigate. The fingers can delicately revolve a small object and investigate it from every angle. They can feel not only its shape but its texture. For the fingers, since they’re no longer required to be put flat on the ground in support of the body, have sensitive pads at the end, covered with tiny ridges of skin to enhance the sense of touch. Every gorilla in fact has its own unique finger prints just as we have.The gorilla family spends its day gently grazing and there’s plenty of time for play. Half-grown, blackback males regularly have wrestling matches.

Sometimes they even allow others to join in. Though they may play games, you don’t forget that these are the rulers of the forest and the great silverback is king of the whole group. He is so enormously strong that he need fear nothing except a man armed with a spear or a gun. No enemies and an unlimited supply of food that can be gathered by simply stretching out an arm, the gorilla has no need to remain particularly agile in either body or mind.

6. 1994 - A rose by any other name…

While filming The Private Life of Plants, Sir David noticed the world's largest flowering plant had quite a racy name – the Amorphophallus Titanum.

Instead, he gave it another name in his script - titum arum - coining the plant's common name in the process. But as well as naming species, many plants and animals have been named after Sir David. They include a flightless beetle, a species of hawkweed found only in the Brecon Beacons and a long-necked dinosaur called the Attenborosaurus.

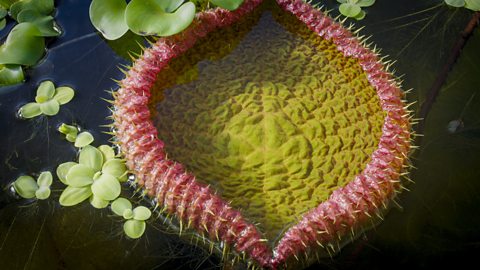

The moment Sir David gave the world's biggest flowering plant its common name - and made a scientific discovery. (The Private Life of Plants, 1994)

One of the most extraordinary of these insect enticers lives here in the tropical rainforest of Sumatra. It only flowers once in a thousand days and when the flower develops, it only lasts for three days, so very few people have seen it. But here it is. Technically it’s a whole group of flowers clustered around this, but you could be justified for regarding it as one flower. And if you do that, well then this is the biggest flower in the world. It’s related to the dead horse arum but it’s nine feet tall and three feet across. It’s amorphophallus titanum, the titan arum.

The function of this great spike in the middle is to produce a smell (coughs) and if you smell it, its smells very strongly of bad fish and this apparently attracts insects. It's come along here and go down into this great funnel to these small flowers that grow at the base.

Until this film was taken, no one was sure what insects pollinated the titan arum. As we watched, we saw that, without doubt, the job was done by tiny sweat bees. Like other arums, the male flowers form a band at the top - below them the female flowers with long, yellow-tipped stigmas. The bees seemed to find some reward on the stigmas for they crawled all over them distributing the pollen they had brought with them.

But why should the titan arum produce the biggest bloom in the world to attract such tiny pollinators? To be effective, these bees must bring pollen from another bloom, but since the plant is rare and only flowers once in three years, the nearest may be miles away. It’s not easy to spread perfume over such distances in the still, humid air of the rainforest. Perhaps the best way to do so is to disperse it from the top of a towering spire, like smoke from a factory chimney.

7. 2001 - Your first glimpse

Without the ambition and persistence of Attenborough and his collaborators, millions of us may never have seen some of the world's rarest creatures.

It's been a constant theme throughout his career, beginning with Zoo Quest in the 1950s, when he famously caught the elusive Komodo Dragon on film for the first time. But in 2001, we were given an insight into a strange new world, when Attenborough narrated The Blue Planet. The series introduced millions to the wonders of the deep sea and was the first time some species, including the hairy angler fish and the Dumbo octopus, were captured on film.

An extraordinary creature is discovered in the ocean depths. (The Blue Planet, 2001. Clip courtesy of WHOI)

This deep sea octopus is about the size of a beach ball and has been nicknamed ‘Dumbo’. An umbrella of skin between its tentacles and its extraordinary flapping ears allow ‘Dumbo’ to hover effortlessly over the sea floor as it searches for food.

8. 2015 - Pushing boundaries

From colour broadcasts to 3D television, Sir David has always been at the forefront of pioneering technology in broadcasting.

In 2015, he dived 1,000ft in a submersible off the Australian coast to film previously unseen parts of the Great Barrier Reef, breaking the record for the deepest ever dive on the reef. He also collaborated with the Natural History Museum on a virtual reality project, and filmed BBC series – such as Planet Earth II and Wild Isles – in Ultra HD. Next time you tune into a major Attenborough documentary, you can be pretty sure you're witnessing a breakthrough in future broadcasting technology.

9. 2015 - Saving the world

Sir David has always said he didn't start making programmes with conservation in mind - he simply enjoyed observing the natural world.

But as time passed, he became aware that the animals and habitats he was filming were under threat. He's authored documentaries which overtly tackle environmental issues but prefers a subtler approach, showcasing the natural world in the hope we might be inspired to preserve it. Counting President Obama among his biggest admirers, Sir David has done more than almost any other person to help millions of us understand and appreciate the wonders of the world around us.

Where next?

We've been fortunate to collaborate with the BBC's Natural History Unit and several of Sir David Attenborough's landmark programmes to bring you curriculum-mapped video resources to support your teaching.

Four ways Sir David Attenborough films can help with science learning. document

An article for teachers by primary science educator Claire Seeley, explaining how natural history films like The Green Planet help bring science learning to life.

How harp seal pups can help children understand about climate change. document

An article for teachers by Frozen Planet II scientist Dr James Grecian, discussing Sir David Attenborough's influence and how teachers can inspire new generations with an interest in the natural world using programmes like Frozen Planet II.

Blue Planet Live. collection

A collection of short films from the BBC series Blue Planet Live, suitable for use with pupils aged 7-11, exploring our oceans and its wildlife to find out how marine life is coping in the face of increasing environmental pressure.

Watch again: Frozen Planet II – Science Live Lesson. video

A half-hour curriculum-linked lesson for primary schools exploring the coldest places on Earth and the impact of climate change on the icy habitat of harp seals.

Watch again: Blue Planet – Live Lesson. video

This half-hour curriculum-linked programme, originally broadcast in 2019, was created in collaboration with Blue Planet Live and was designed to help 7-11 year-olds find out what constitutes a healthy ecosystem and what the threats are to our oceans (such as plastics and overfishing).

Watch again: Green Planet – Live Lesson. video

A tropical plant-themed science lesson for 7-11 year-olds featuring amazing footage from the Green Planet series following Sir David Attenborough's exploration of the extraordinary ways plants have learnt to survive and thrive in almost every environment.