| Transplants save lives | More than 12.7 million people have said they want to help others to live after their death by joining the NHS Organ Donor Register. Figures taken from the UK Transplant website state that in the year to the end of March 2005 there were: - 1,783 kidney transplants

- Organs from 762 people who died were used to save or dramatically improve lives through 2,242 transplants

- 2,375 people had their sight restored through a cornea transplant

- 86 people received a combined kidney/pancreas transplant

Right now, more than 7,000 people in the UK need an organ transplant. To find out more about organ donation and transplantation call: The Organ Donor Line on 0845 60 60 400 or visit www.uktransplant.org.uk |

Last Christmas, my family didn’t give presents to each other. We didn’t have a Christmas tree. On Christmas day, our lunch was eaten in a big canteen, without crackers, alcohol or silly hats. Most of the day was spent in silence. It wasn’t because we don’t celebrate Christmas, far from it, my Father’s a priest. But Christmas this year wasn’t at home. It was spent in an air locked booth in Great Ormond Street Hospital, after my youngest brother Gareth had had a heart transplant. | "My cuddly little brother had gone from chubby, spotty teenager to a boy with only months to live in less than a year." | | Hannah Barham |

Gareth had been waiting to have a transplant since August, having been struck down with a random virus called Dilated Cardiomyopathy in May of the same year. By December, he was unable to walk more than a few metres without stopping to catch his breath, he’d lost so much weight and his skin was yellow as a result of his liver not working properly. My cuddly little brother had gone from chubby, spotty teenager to a boy with only months to live in less than a year. On the 21st of December, at 11 o’clock at night, we received a phone call. “There’ll be an ambulance at your house in fifteen minutes, make sure you’re ready.” By now, we all knew what to do. While my dad made phone calls, my mum packed and I sat with Gareth. We all knew what could happen, and tried to distract ourselves and him, but deep down we were scared. The ambulance arrived, we said our goodbyes, and they drove off into the quiet night. At quarter past one another call came, but this time, it was a familiar voice. “I’m sorry Hannah”, said my father, choking back tears of frustration. “The heart wasn’t good enough to risk the operation, we’ll be back by ten.”  | | Harry, Hannah and Gareth, Durham, 2005 |

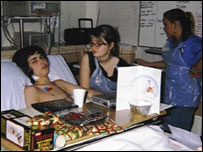

By the time of their return, the whole family was depressed. Gareth had only turned 15 on the 16th December, and when asked what he wanted as a present, his only response would be: “a new heart.” Getting through that day had been hard enough, coping with Christmas would be awful. We had to resign ourselves to the idea that Christmas would be miserable. We all slept through most of the 22nd, and then, at one o’clock on the morning of the 23rd, came another phone call. “There’s an ambulance parked outside your house. We didn’t want to tell you unless we were sure, but this heart looks perfect.” Within two minutes, Gareth and my parents were driving off, as we yelled farewells through the windows. By half past two, Gareth was being prepped for theatre, and by midday, the operation was over, with very few complications. On Christmas Eve, my brother Harry and I travelled up to join them. We didn’t really know what to expect. Would Gareth be awake? How would he look? Dad picked us up from Kings Cross, with a look of relief on his face. He assured us that the scar would be covered, but that Gareth was coming in and out of consciousness and was making very little sense.  | | Gareth on Christmas Day 2004 |

We eventually entered the room where Gareth had been placed; Harry fainted. While Dad had left to collect us from the station, they had removed Gareth’s bandages. He had been well stitched up, but the long line down the centre of his chest was covered in dried blood, and jutted out of his skin where the rib cage had been sawn in two. He was, however, looking better than he had done for months. His skin had returned to pink rather than yellow as the blood was pumping normally, and his eyes when he did wake up looked clear and alive. He said very little, and what he did manage to say made very little sense: “Mum, don’t forget you’ve left the pasta cooking.” “Hannah, wake me up for Neighbours, won’t you?” However much we tried to tell him that in the middle of the night, he wouldn’t be able to watch Neighbours, he didn’t understand. Of course, we weren’t the only ones in the hospital that Christmas. Given that the hospital’s position as one of the best children’s hospitals in the world, there were people from every religion and many different countries. All the children were provided with presents, all carefully wrapped by volunteers.  | | Christmas Day 2004 |

Because Gareth was so much older than most of the other patients, they’d gone out and bought him special gifts, rather than the cuddly toys the smaller children received. He was grouchy, continuously apologising for “ruining our Christmas”. He didn’t understand that by doing so well in his operation, he had made our Christmas one of joy and relief, rather than the frustration and misery we had been expecting. Gareth had to wait nearly six months for a donor organ; he was one of the lucky ones. Last year,400 people died while waiting for an organ transplant. That shouldn’t be the case. Signing up to be an organ donor is easy – go to www.uktransplant.org.uk to join the register. One day, it could be you or a loved one needing a transplant. Trust me, you wouldn’t enjoy the wait. Gareth’s transplant was truly the best Christmas present my family could have ever received. It’s easy to save a life – please, please, sign the register. It could be the best thing you do this Christmas. |