In bringing Vladimir and Estragon - that Laurel and Hardy of existentialism - back to the stage, Sir Peter Hall is reprising a directorial task he first undertook some 50 years ago. While the play may, of necessity, have lost much of its shock value, nevertheless its impact is still profound. As Sir Peter intimates in his programme notes, whereas the truculent Jimmy Porter of Look Back in Anger is firmly stuck back in the 50s - a long-lost era of teddy boys, milk bars and sweaty jazz clubs - the two anti-heroic tramps and their parallel universe, redolent with metaphorical significance and poignancy, never seems to date. Vladimir and EstragonExamining our lives and finding in them great pathos, as well as wit and humour, Beckett is the supreme master of the human condition.  | | Dobie as Estragon and Laurenson as Vladimir |

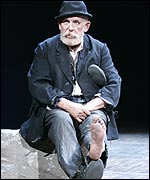

Through telling, rhythmical poetry that positively resonates with musical cadences and significance, he looks deep into our psyche and finds both tragedy and comedy in equal measure. Vladimir and Estragon are two tramps (in the original Paris production they were clowns, but for the London stage, Sir Peter turned them into tramps and the 'casting' has stuck ever since). Their wait for Godot is a recurring leitmotif, constantly peppering their enigmatic conversations as they debate their condition along with life, the universe and everything. "I know, we'll hang ourselves," "No, we haven't got any rope and anyway we're waiting for Godot," "Oh yes!" And that wonderfully askance humour: "There, that passed the time didn't it?" "Well, it would've passed anyway." Pozzo and LuckyInto their frustrating world comes the domineering Pozzo and his manservant (slave might be nearer the mark) Lucky, who is anything but.  | | Alan Dobie as Estragon |

Seemingly dumb and shackled, with a symbolic rope around his neck by which he is led on to the stage, Lucky fetches and carries for his master. The dumbness, however proves another illusion and Lucky eventually delivers the play's only soliloquy, a blisteringly adroit, thought-provoking, metaphorical commentary on humanity - our lives in a five-minute snippet. Perhaps the most poignant lines of the play, however, are Pozzo's. Having been struck blind, in the second act, while Lucky is now deaf, he eventually tires of Vladimir's interminable questions. "It's abominable! Have you not done tormenting me?" he screams. "One day! One day! One day I went blind, one day I'll go deaf, one day we are born, one day we shall die! It's the same day." And to think, back in 1955, one critic said the play had "only a vaguely suggested meaning". A magnificent revivalJames Laurenson and Alan Dobie are excellently cast as Vladimir and Estragon, balancing humour and pathos superbly and delivering those wonderfully musical lines with gusto and poignancy.  | | Dormer as Lucky and Laurenson as Vladimir |

The finely honed comic routine where they swap three hats among the two of them was pure Marx Brothers and had the audience roaring with joy. In lesser hands, one could easily tire of these two enigmatic characters as they bumble their way through their plight, but one feels a genuine concern and empathy for this Vladimir and Estragon, as their fate unfolds. No less convincing are support players Terence Rigby (was that really him in Softly Softly all those years ago?) as Pozzo, and his physically hampered sidekick Lucky, played brilliantly by Richard Dormer. His beautifully performed soliloquy - reminiscent of Winnie in Happy Days - will live with me for a long time. The unappealing pair's hate-hate relationship sizzles and burns as they provide an enlightening counterpoint to the main characters. So does the enigmatic Godot ever turn up? Sorry - you'll just have to see the play. You could do a lot worse than starting with Sir Peter's magnificent revival in Bath. |