Love took my hand

A celebration in music and word of the life and works of the priest and poet George Herbert, from the Chapel of St John's College, Cambridge.

A celebration in music and word of the life and works of the priest and poet George Herbert, from the Chapel of St John's College, Cambridge. Herbert is one of the most celebrated of the Seventeenth-Century metaphysical poets. He studied and worked in Cambridge, before going on to be ordained and continuing to write poetry to 'God's glory'. The service is led by the Dean of Chapel at St John's, the Reverend Dr Mark Oakley, who looks at Herbert's works in the context of the Easter season. The poems are read by members of the College, and the Chapel choir leads the congregation in a selection of works with Herbert's texts, including the hymns 'King of glory, King of peace', and 'Teach me, My God and King'. Director of Music: Andrew Nethsingha. Organist: George Herbert: Producer: Ben Collingwood.

Last on

Script of Service

RADIO 4 OPENING ANNOUNCEMENT:

At ten past eight on BBC Radio 4 and BBC Sounds it’s time now for Sunday Worship.

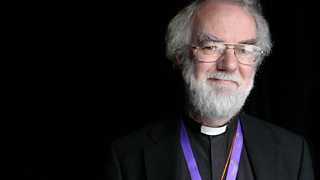

MARK:

Good morning and a very warm welcome to the Chapel of St John’s College, Cambridge. I’m Mark Oakley, the Dean here at St John’s. The College was founded in 1511, and is, today, a diverse and international academic community that enjoys, amongst many other things, a renowned choral tradition, helping to nurture our life together as well as develop the musical talent of our students. In this season of Easter our service begins with the choir singing a work which celebrates the joy of the risen Christ: Look there! the Christ, our Brother, comes.

CHOIR/ORGAN: Look there! the Christ, our Brother, comes (William Albright)

MARK:

In a short while, Cambridge will be hosting the triennial conference of the George Herbert Society. Herbert was a poet and priest who lived from 1593 to 1633. He studied here at the university, at our neighbouring Trinity College, and at the end of his first term he wrote to his mother and included a couple of sonnets. Only a fragment of the letter exists today but we can read his words:

READER 1:

My meaning (dear Mother) is in these sonnets, to declare my resolution to be, that my poor Abilities in Poetry, shall be all, and ever consecrated to God’s glory.

MARK:

Although blighted by ill health, Herbert’s time at Cambridge was productive and eventually he was elected to be the university orator. Later, his life was to take a new direction, towards ordination and parish ministry outside Salisbury, but that early commitment to write poems for God’s glory never left him. This morning we celebrate his life and poetry within this season of Easter, a season he so loved and wrote about often. And now we sing one of his poems ‘Praise’, which begins ‘King of glorie, king of peace’.

CHOIR/ORGAN/CONGREGATION: King of glory, King of peace (Gwalchmai)

MARK:

Most of Herbert’s 170 or so poems are about God, but they are deeply in tune with the shadows of the human heart and the agitated human mind. He refers to his thoughts as a ‘case of knives’ at one point. He uses day to day imagery, and a familiar voice, to help us recognise our own world, and our inner lives, but suggests too how they both wrestle, and are infused, with that other world of distillation and refreshment for which religious faith longs, and which prayer seeks to find a path towards. Often Herbert admits how, when it comes to God, he can be adolescent in his mood and behaviour, banging tables and wanting an argument. In response, God simply is who God is, a friend who, and we find this image in his poems more than once, holds out his hand to us, smiling. In the words of St Augustine, ‘proud humanity can only be saved by the humble God’. In the poem ‘The Dawning’, there is the dawn of the breaking day, but we also hear something dawning in Herbert himself.

READER 2:

Awake sad heart, whom sorrow ever drowns;

Take up thine eyes, which feed on earth;

Unfold thy forehead gather’d into frowns:

Thy Saviour comes, and with him mirth:

Awake, awake;

And with a thankfull heart his comforts take.

But thou dost still lament, and pine, and crie;

And feel his death, but not his victorie.

Arise sad heart; if thou dost not withstand,

Christs resurrection thine may be:

Do not by hanging down break from the hand,

Which as it riseth, raiseth thee:

Arise, Arise;

And with his buriall-linen drie thine eyes:

Christ left his grave-clothes, that we might, when grief

Draws tears, or bloud, not want an handkerchief.

MARK:

Herbert sees through the half-light that the graveclothes of Christ are there to wipe away his tears and hurt. He knows he musn’t break from the hand that holds him tight. He tells himself again and again to ‘arise’ with Christ, just as in the first part of his poem ‘Easter’, Herbert tells his heart to rise with his Lord, knowing that the endless loving commitment of Christ towards him is what will make his own life more ‘just’, which can mean ‘tuned well’, or, in tune with itself. Ralph Vaughan Williams set this poem, appropriately with all the poem’s musical references, as part of his Five Mystical Songs.

CHOIR/ORGAN: Rise heart; thy Lord is risen (Vaughan Williams)

MARK:

The ancient Assyrian people had a word for prayer that was the same word for unclenching a fist. The life with God slowly helps us release the gripped life. Catch yourself this week and see how many times your fist is tight with stress and defence. To be opened out is liberating but often hard and dislocating. It takes self-scrutiny and trust. And the intimacy with God we find in Herbert comes from a confidence in the inviolability of their relationship. This means he can be both reverent and rebellious, devout and derelict, hostile but silenced by love. Herbert is unafraid to reason but unashamed to adore, and in all the honesty, so a relationship with God is forged. In this relationship, as in everything else, honest complexity must never be replaced by a dishonest simplicity. He voices questions and confusions but he knows that he can only ever be loved from the outside, that his life is dependent on receiving goodness and not merely on our control of it. We need to hold the hand that is open to us.

In the gospels Jesus, with the same love that creates life, takes the sick and the oppressed by the hand and pulls them up. He also holds out his hand to touch those with diseases that made them so isolated by fear. We hear of two such healings now, from chapter 8 of St Matthew’s gospel, followed by some lines of Herbert: ‘Thou that hast given so much to me, Give one thing more, a grateful heart’, set to music by Mary Plumstead.

READER 3:

When Jesus had come down from the mountain, great crowds followed him; and there was a leper who came to him and knelt before him, saying, “Lord, if you choose, you can make me clean.” He stretched out his hand and touched him, saying, “I do choose. Be made clean!” Immediately his leprosy was cleansed. Then Jesus said to him, “See that you say nothing to anyone; but go, show yourself to the priest, and offer the gift that Moses commanded, as a testimony to them.” When Jesus entered Peter’s house, he saw his mother-in-law lying in bed with a fever; he touched her hand, and the fever left her, and she got up and began to serve him.

CHOIR/ORGAN: A grateful heart (Plumstead)

MARK:

For Herbert, our restlessness, the unsatisfied longing of the homesick heart, is the compass that sets us back on the journey towards God. This sense of restlessness is captured in Herbert’s poem, The Pulley. Here, Herbert imagines God at creation bestowing good things on human beings but deciding to keep rest from them so that they remain restless, their sense of incompleteness prompting them to look out of themselves for a peace the world cannot give.

READER 1:

When God at first made man,

Having a glass of blessings standing by,

“Let us,” said he, “pour on him all we can.

Let the world’s riches, which dispersèd lie,

Contract into a span.”

So strength first made a way;

Then beauty flowed, then wisdom, honour, pleasure.

When almost all was out, God made a stay,

Perceiving that, alone of all his treasure,

Rest in the bottom lay.

“For if I should,” said he,

“Bestow this jewel also on my creature,

He would adore my gifts instead of me,

And rest in Nature, not the God of Nature;

So both should losers be.

“Yet let him keep the rest,

But keep them with repining restlessness;

Let him be rich and weary, that at least,

If goodness lead him not, yet weariness

May toss him to my breast.”

MARK:

But what, some four hundred years later, can we learn from Herbert about how to reconnect with God and with our neighbour now? It begins by our heart waking up, rising and taking another’s hand. If we want to celebrate Easter with integrity there are reconnecting consequences at a very personal and local level: we might need to go and phone the person we have grown distant from, we might need to write to the person we had a row with, we may need to say sorry to someone, or tell them we love them, we may need to see where winter has taken over our heart and how we have grown prickly, how unhappiness may be spreading through us, how we’ve stopped thinking about the moral consequences of how we spend money, trash things easily, forget the unseen, or how we may confuse compassion for justice. A wintered life turns to Spring by such seemingly small movements of resurrected love and will. It is what the other poet, Gerard Manley Hopkins, prays for when he writes of Christ: ‘Let him easter in us, be a dayspring to the dimness of us’. Or, in Herbert’s words’, ‘Teach me, my God and King, in all things Thee to see’.

CHOIR/ORGAN: Teach me My God and King (Michael Rose)

MARK:

When he was dying Herbert sent a collection of his handwritten poems, which had never been published in his lifetime, to his friend Nicholas Ferrar at the community of Little Gidding with a note: “if he think”, wrote Herbert, “it may turn to the advantage of any dejected poor soul, let it be made public; if not, let him burn it”. Ferrar thankfully did not go near the fire. When Herbert sent his poems to his friend he had arranged them in order. The very last one was simply called Love. The message was clear – for the Christian that must always be the last word.

READER 2:

Love bade me welcome: yet my soul drew back,

Guiltie of dust and sinne.

But quick-ey’d Love, observing me grow slack

From my first entrance in,

Drew nearer to me, sweetly questioning,

If I lack’d any thing.

A guest, I answer’d, worthy to be here:

Love said, you shall be he.

I the unkinde, ungratefull? Ah my deare,

I cannot look on thee.

Love took my hand, and smiling did reply,

Who made the eyes but I?

Truth Lord, but I have marr’d them: let my shame

Go where it doth deserve.

And know you not, sayes Love, who bore the blame?

My deare, then I will serve.

You must sit down, sayes Love, and taste my meat:

So I did sit and eat.

MARK:

It is an unusual religious poem. It never uses the word God but simply ‘Love’. How would our faith change if we did the same? This poem came to mind a few years ago. I was brought up by my grandparents and my grandfather had flown in the Royal Air Force in World War 2; he was a bit of a hero to me but he never spoke about his experiences, except one day mentioning ‘Dresden’ and weeping. I didn’t understand then as a young boy but I grew up and learned why. He has since died but in 2015 I was asked to preach in the reconstructed Frauenkirche in Dresden. He was very much in my mind. On the way to the train station at the end of my visit the taxi driver asked me why I was in Dresden and I told him I had always wanted to come. ‘Why?’ he asked. I took a deep breath; ‘because my grandfather was a navigator of a Lancaster bomber and on 14 Feb 1945 I know he flew here as part of the bombing raid and he could never talk to me about it’. The man was quiet and then said ‘ah, that was the night my mother was killed’. He pulled over the car and turned the engine off. He then turned round to me, put out his arm and said ‘and now we shake hands’.

The taxi driver did what Love does in the poem, smiling, he took my hand. That man, like me, knew the facts. He knew the horrors of the night, he had lived his loss, learned about the thousands dead. But he knew more. He had become wise. We rightly ask what it might mean to be loyal to the past, but the more urgent question is how can we be loyal to the future? As Herbert knew, when love stretches out a hand, new life begins to take shape and a way towards a fresh answer to that question is opened up. It is the way of resurrection.

CHOIR/ORGAN/CONGREGATION: A brighter dawn is breaking (Nun lasst uns gott)

READER 1:

Let us pray.

We pray for those who reach out their hands to the wounded, to the refugee, to all who are hurting or lost or diminished. And we pray to be such people ourselves.

We pray for all those who are caught up in the horrors of war, violence, want and oppression. In particular we continue to pray, as we daily do, for the people of Ukraine.

O Lord our God, whose compassion fails not: support, we entreat you, the people on whom the terrors of invasion have fallen; and if their liberty be lost to the oppressor, let not their spirit and hope be broken, but stayed upon your strength till the day of deliverance; through Jesus Christ our Lord.

Amen.

Let us gather up all our prayers and hopes in the words which Jesus gave us:

Our Father, who art in heaven,

hallowed be thy name;

thy kingdom come; thy will be done;

on earth as it is in heaven.

Give us this day our daily bread.

And forgive us our trespasses,

as we forgive those who trespass against us.

And lead us not into temptation;

but deliver us from evil.

For thine is the kingdom,

the power, and the glory,

for ever and ever. Amen.

MARK:

May God, who is in this world as poetry is in the poem, awaken your heart to the fresh joy of Christ's resurrection, that you may follow George Herbert, and all the saints and friends of God, in the ways of faith, hope, and love; and the blessing of God almighty, the Father, the Son, and the Holy Spirit, be among you and remain with you always. Amen.

CHOIR/ORGAN: Let all the world in ev’ry corner sing (Vaughan Williams)

RADIO 4 CLOSING ANNOUNCEMENT:

‘Let all the world in every corner sing’ – a poem of George Herbert, set to music by Ralph Vaughan Williams, bringing to a close Sunday Worship which was recorded in the Chapel of St John’s College, Cambridge. It was led by the Dean, The Reverend Dr Mark Oakley. The Director of Music was Andrew Nethsingha, the organ was played by the Herbert Howells Organ Scholar George Herbert, and the producer was Ben Collingwood. The programme is available now on BBC Sounds from where you can also click through to a copy of the script. If you’d like to hear more from St John’s then today’s BBC Radio 3 Choral Evensong at three o’clock also comes from the College Chapel. Next week’s Sunday Worship comes live from Newcastle Cathedral.

Broadcast

- Sun 8 May 202208:10BBC Radio 4