Reading’s Puritans turn away Shakespeare

By Alexandra Johnston, REED's Founder and editor of Berkshire

When today's audiences go to concerts or outdoor performances in Reading's renovated Town Hall or the Abbey Gardens they are being entertained on the same site as where the company that made William Shakespeare famous played four hundred years ago.

Reading, situated as it is on one of the main roads west from London, welcomed players from as early as 1381. And there is evidence of eight visits by Shakespeare’s company The King’s Men between 1618 and 1630.

![]()

Much ado near me

Hear more Shakespeare stories on BBC Radio Berkshire

![]()

Shakespeare Festival 2016

The BBC celebrates the genius of the bard

During the reign of King James, The King’s Men came five times and played for the mayor and council but, during the reign of King Charles, they presented their license three times between 1627 and 1632 but were paid not to perform and sent away.

The increasing Puritanism of the Reading authorities seems to have made them increasingly concerned about the appearance of travelling companies and five notations in the Corporation Diaries from 1629 to 1631 indicate that the presented licenses were being carefully inspected by the civic authorities.

The preferred playing place in Reading, curiously, has in the last thirty years once again become the site of the Benedictine Abbey as it was from the late fifteenth century until the eighteenth century. Since 2000, the concert hall in the old Town Hall has become the centre of the city’s musical life and the since the 1980s the gardens around the abbey ruins have become a favourite place for open air theatre, including performances of Shakespeare's plays.

Where would Shakespeare’s men have performed in Reading?

The records of St Laurence Church (still a part of central Reading) are unusually detailed from the 1490s and record an extensive tradition of performing religious plays. For the most part, the parish preferred to perform their plays in the precinct of the Abbey.

The Abbey was a major pilgrimage destination and it had a very large guest house to accommodate up to 400 pilgrims – the Hospitium of St John. In 1486, the Abbey school became a Royal Grammar School of Henry VII and was moved into the refectory of the Hospitium.

When the town of Reading was given its royal charter after the dissolution of the Abbey in the mid-sixteenth century, the town hall was established in the old Greyfriars church but that space soon proved too small.

The Hospitium had been largely untouched by the destruction of the Abbey and in the 1580s the town council created a new town hall in the refectory of the Hospitium by inserting a second floor into the room.This new town hall would have been the place where the King’s men performed for the mayor and council, making the site of the Abbey once again a playing place. Unfortunately, the refectory became structurally unsound in the eighteenth century and it was taken down and the site incorporated into the first phase of the building of the town hall that served Reading until 1976.

However, the main building of the Hospitium is the only part of the Abbey that still stands and houses a children’s nursery today. From it we can still experience some sense of the architectural magnificence of the Abbey buildings.

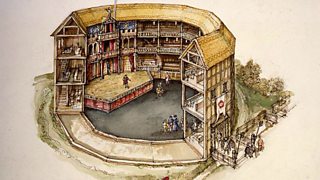

Shakespeare on Tour

From the moment they were written through to the present day, Shakespeare’s plays have continued to enthral and inspire audiences. They’ve been performed in venues big and small – including inns, private houses and emerging provincial theatres.

BBC English Regions is building a digital picture which tracks some of the many iconic moments across the country as we follow the ‘explosion’ in the performance of The Bard’s plays, from his own lifetime to recent times.

Drawing on fascinating new research from Records of Early English Drama (REED), plus the British Library's extensive collection of playbills, as well as expertise from De Montfort University and the Arts and Humanities Research Council, Shakespeare on Tour is a unique timeline of iconic moments of those performances, starting with his own troupe of actors, to highlights from more recent times. Listen out for stories on Shakespeare’s legacy on your BBC Local Radio station from Monday 21 March, 2016.

You never know - you might find evidence of Shakespeare’s footsteps close to home…

Craig Henderson, BBC English Regions

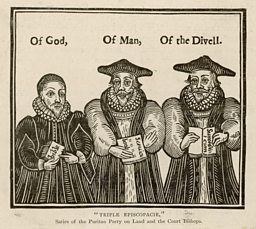

The Puritanical backlash against theatre

One of the most peppery of the Puritans in Elizabethan times is the pamphleteer Philip Stubbes.

Stubbes is perhaps best known for his popular book The Anatomie of Abuses (1583) in which he claims to expose some of the supposed ‘abuses’ in Elizabethan society and the theatre comes in for particular stick.

In Shakespeare and other dramas of the day it is the men who also play female parts. Stubbes and his supporters, known as anti-theatricalists, refer to men who dress up as women as “monsters of both kinds, half women, half men”. They consider such cross-dressing as a depravity.

Carrie Blais, commentating on the life of Philip Stubbes, writes: “Although stage cross-dressing was a necessity brought about by the all-male Elizabethan stage (women in England were barred from performing on the public stage until after 1660), critics have noted that Shakespeare’s use of cross-dressing is complex, and in fact may question the patriarchal structures of his time.

“Shakespeare attempts to undo the policing of gender boundaries and this attempt may perhaps be partly why the anti-theatricalists were so anxious about 'real' gender boundaries.”

Stubbes also argued that plays were magic. They had the power to turn men into aggressive beasts on stage – and that audiences might be drawn into the magic by imitating what they see.

Dismissing them as "filthy plays and bawdy interludes" Stubbes goes so far as to accuse them of being the work of the devil.

His work was a big success – it had four editions – clearly striking a chord with like-minded Puritans who also believed, like Stubbes, that "leisure leads to vice".

Related Links

Shakespeare on Tour: Around Berkshire

![]()

Reading child prodigy retires

W.R. Grossmith says farewell at 11

![]()

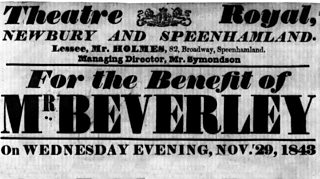

Mr Holmes keeps the fires burning bright for Hamlet

Newbury and Speenhamland audiences flock to the theatre

![]()

Shakespeare performed in Windsor Castle by Royal Command

Queen Victoria enjoys a performance in Windsor

Shakespeare on Tour: Around the country

![]()

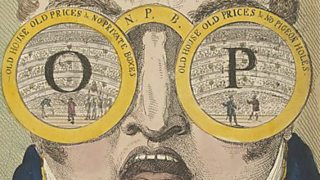

The 1809 ticket price riots

The most famous riots in the history of theatre

![]()

Cambridge students put on a Christmas satire

Shakespearean style 'Footlights'

![]()

North West's influence on Shakespeare's success

Plus, the small Cheshire town that attracted Shakespeare's players

![]()

Salisbury shadows play Shakespeare

A dreamy performance of Shakespeare