You Might Never Have Read Macbeth

Emma Smith takes a road trip to learn more about how Shakespeare's First Folio for BBC Radio 3's Sunday Feature

Marmalade. A new scarlet suit. Candles. A spinning top for his toddler son. Two copies of Shakespeare’s collected plays.

Edward Dering’s shopping list for 5 December 1623 goes from the mundane to the momentous. This fashionable young Kentish nobleman is the first person to have bought the book we now know as one of the first Folio’s – a book that can claim to be the most significant in the English language.

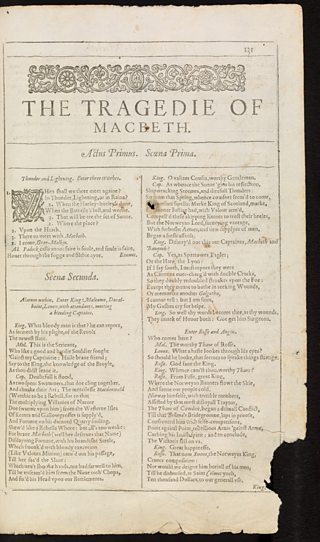

Shakespeare’s plays had been published during his lifetime – or at least some of them had. But 18, including Macbeth, Julius Caesar, Twelfth Night and The Tempest, were printed in a folio once owned by Dering – and without this, they would probably have been totally lost to history. The collected edition of his plays also included the only attested likeness of the dramatist: the engraving familiar to us from reproductions and parodies, of a balding domed forehead, stubbly chin, and broad stiff ruff. It established Shakespeare’s reputation as a serious dramatist, not simply a writer for the ephemeral world of the theatre, but someone whose works would last: ‘not of an age, but for all time’, as his rival playwright Ben Jonson wrote in a puff for the volume.

But Shakespeare’s reputation was not secure in these early years of the seventeenth century. His plays gradually dropped out of the performance repertoire, looking old-fashioned as newer writers captured audience interest. When Shakespeare died in 1616, it was as if he had been forgotten. No elegies or obituaries, no obvious public mourning, no place for him in Poets’ Corner in Westminster Abbey.

It was this book, which curated his legacy and began to spread it beyond the small world of London theatres. Within a few years, copies of the book had been bought by readers in the Scottish borders, in Wales, in Suffolk, in Nottinghamshire, and, before long, taken as far as Holland and France. It was a book that appealed equally to men and to women, adults and children, and one that was at home in protestant and catholic households. It could occupy a middle ground during the heated and divisive politics of the English civil war, when both supporters of both the cavalier and parliamentarian factions are known to have enjoyed it.

These early readers do not put Shakespeare on a pedestal. Their reading is often done with a pen in hand, underlining favourite quotations, adding their own opinions of what they read, or sometimes correcting errors in the text. Greasy marks and the occasional ring from the foot of a wine glass suggest they may well have studied it at the table. Children have doodled in the margins; young adults have practiced elaborate, grown-up signatures in its blank spaces. In the years before the Folio became a valuable museum object, it was something much more important: a book that people read, enjoyed, and cared about. It’s that process that made Shakespeare, Shakespeare.

By Professor Emma Smith