Puritan backlash in Exeter

Playing companies such as Shakespeare’s were becoming unpopular in parts of the country, such as Devon, as the increasingly puritanical authorities began to turn them away – to pay them not to perform.

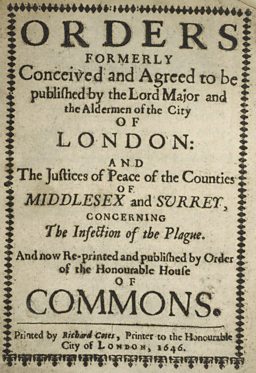

Theatre was generally regarded by the Puritans as being immoral, indecent and extravagant and it’s a tension which was to rise until finally, in 1642, Parliament suppressed all stage plays, leading in 1648 to an order for all playhouses to be pulled down. Although the orders could not be strictly enforced – it meant theatres were practically closed from 1642 until the restoration in 1660.

![]()

Much ado near me

Hear more Shakespeare stories on BBC Radio Devon

![]()

Shakespeare Festival 2016

The BBC celebrates the genius of the bard

We see evidence of this around Shakespeare’s time in various parts of Devon. In Barnstaple, where other troupes such as Queen Anne’s Men and the Prince’s players made more regular visits during the first two decades of the 17th century, yet by 1617 the civic authorities became increasingly hostile to players as puritan sympathies grew locally.

The picturesque harbour town of Dartmouth on the main south coast road from Exeter to Plymouth attracted two visits in the same year by the touring company of the King’s Men.

On 21 October 1633 they were handsomely rewarded with £1, and the same again when they returned on 5 June 1634. There survives no other evidence of their travels in the south-west during this period, though they must have made other stops along their way.

Both Exeter and Plymouth simply dismissed players without noting down their identity at this time. On the 28th of June 1634, the Exeter Receiver merely recorded the following: ‘Item paid mr Maior ffor soe much hee gaue the players to send them out of towne…[£] 002.’

Could this have been the King’s Men? A similar entry was recorded at Plymouth the same year.

Although Shakespeare had died many years before, some of his plays are known to have remained in the company’s repertory, notably Richard III and The Taming of the Shrew (revived at court in November 1633, soon after their gig at Dartmouth).

The possible Dartmouth venue for Shakespeare’s actors still survives

The mid-15th century church of St Saviour’s had been acquired for use by the town in 1586 and was a possible performance venue for players, as it had definitely been used by Leicester’s Men in 1570. The church has undergone numerous alterations over the centuries, from the 15th to the 20th but it retains some remarkable early features -- a handsome late 15th c. rood screen, still in the original position, an ornate and colourful Elizabethan altar and an Elizabethan oak pulpit. By 1633 the south porch had been built, the tower raised, the north and south aisles rebuilt and a gallery added at the west end of the nave. St Saviour’s is still the principal parish church of Dartmouth.

Exeter’s ‘cold shoulder’ – two years after Shakespeare’s death

The King’s Men are recorded to have visited the wealthy cathedral city of Exeter only once, in May 1618, when they were not welcomed but dismissed outright, though the payment of £2 4s to leave may still have been considered worth the trip.

Martin Slater was an interesting and enterprising character who was not always what he professed to be

Perhaps it would have been politically tricky to drum the royal troupe out of town without generous payment?

The lead player was named by the Exeter accounting clerk to be Martin Slater, an interesting and enterprising character who was not always what he professed to be. Slater (or Slaughter) had been previously an actor with the Admiral's Men, 1594-97; the Earl of Hertford's Men in 1603; and then most consistently with Queen Anne's Revels company (1608-25).

He was only briefly manager of the King's Revels troupe at Whitefriars Theatre in London in 1608 so his claim to represent The King’s Men in 1618 must be considered highly suspect. In fact he tried using a forged license for The King’s Men again seven years later at Leicester, where £1 was paid on 15 October 1625 ‘to one Slator and his Companie being the Kinges Playors.’

Slater was not the only player in the period bold enough to acquire a copy of a company’s license with intent to recruit some fellow adventurers to tour the provinces, posing as a recognized professional troupe to reap their rewards. The Lord Chamberlain, recognizing the abuse, sent an order to all provincial officials in 1616 to put a stop to the practice, naming Slater among others as follows:

‘wheras Thomas Swynaerton and Martin Slaughter beinge two of the Queens Maiestes Company of playors hauinge separated themselues from their said Company, haue each of them taken forth a severall exemplification or duplicate of his Maiestes Letters patentes graunted to the whole Company and by vertue therof they severally in two Companies wth vagabondes and such like idle persons, haue and doe vse and exercise the quallitie of playinge in diuerse places of this Realme to the great abuse and wronge of his Maiestes Subiectes in generall and contrary to the true intent and meaninge of his Maiestie to the said Company… wherefore to the end such idle persons may not be suffered to continewe in this Course of life

Shakespeare on Tour

From the moment they were written through to the present day, Shakespeare’s plays have continued to enthral and inspire audiences. They’ve been performed in venues big and small – including inns, private houses and emerging provincial theatres.

BBC English Regions is building a digital picture which tracks some of the many iconic moments across the country as we follow the ‘explosion’ in the performance of The Bard’s plays, from his own lifetime to recent times.

Drawing on fascinating new research from Records of Early English Drama (REED), plus the British Library's extensive collection of playbills, as well as expertise from De Montfort University and the Arts and Humanities Research Council, Shakespeare on Tour is a unique timeline of iconic moments of those performances, starting with his own troupe of actors, to highlights from more recent times. Listen out for stories on Shakespeare’s legacy on your BBC Local Radio station from Monday 21 March, 2016.

You never know - you might find evidence of Shakespeare’s footsteps close to home…

Craig Henderson, BBC English Regions

Related Links

The Puritanical backlash against theatre

One of the most peppery of the Puritans in Elizabethan times is the pamphleteer Philip Stubbes.

Stubbes is perhaps best known for his popular book The Anatomie of Abuses (1583) in which he claims to expose some of the supposed ‘abuses’ in Elizabethan society and the theatre comes in for particular stick.

In Shakespeare and other dramas of the day it is the men who also play female parts. Stubbes and his supporters, known as anti-theatricalists, refer to men who dress up as women as “monsters of both kinds, half women, half men”. They consider such cross-dressing as a depravity.

Carrie Blais, commentating on the life of Philip Stubbes, writes: “Although stage cross-dressing was a necessity brought about by the all-male Elizabethan stage (women in England were barred from performing on the public stage until after 1660), critics have noted that Shakespeare’s use of cross-dressing is complex, and in fact may question the patriarchal structures of his time.

“Shakespeare attempts to undo the policing of gender boundaries and this attempt may perhaps be partly why the anti-theatricalists were so anxious about 'real' gender boundaries.”

Stubbes also argued that plays were magic. They had the power to turn men into aggressive beasts on stage – and that audiences might be drawn into the magic by imitating what they see.

Dismissing them as "filthy plays and bawdy interludes" Stubbes goes so far as to accuse them of being the work of the devil.

His work was a big success – it had four editions – clearly striking a chord with like-minded Puritans who also believed, like Stubbes, that "leisure leads to vice".

Shakespeare on Tour: Around Devon

![]()

Shakespeare's acting company come to Barnstaple

Was Shakespeare among them?

![]()

Youthful Tragedian performs Hamlet in Devonport

A warm Devonport welcome for a young Prince Hamlet

![]()

Ira Aldridge in Devon

Ira Aldridge plays in Devonport before returning to London

Shakespeare on Tour: Around the country

![]()

A horse! A horse! My kingdom for a horse!

King Richard III's horse White Surrey is the star of the show

![]()

Modern day Macbeth for Corby steel town

The adaptation encouraged younger viewers to connect to Shakespeare

![]()

Sarah Siddons plays Hamlet in Liverpool

Actress becomes first woman known to have played Shakespeare's Prince of Denmark

![]()

Child prodigy actor prepares to retire as he headlines in Newcastle

W.R. Grossmith says farewell to the stage at 11