What we learned from Hilary Mantel’s Reith lectures

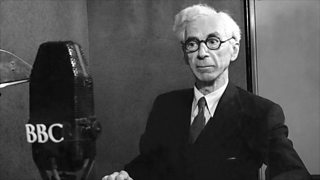

Dame Hilary Mantel (1952-2022) was one of Britain’s most acclaimed novelists. She won the Booker Prize twice for her novels set in Tudor England: Wolf Hall and Bring up the Bodies. In the 2017 Reith lectures, Mantel explored the aims, ideals, constraints and critiques of historical fiction, and the challenges that writers face. We’ve picked out some interesting insights – for more, listen to the lectures.

Mantel initially wanted to be a historian, but settled for novel writing

Realising too late that she should have studied history at university, Mantel became a novelist to channel her interest in the past. She describes initially feeling “morally inferior to historians and artistically inferior to real novelists, who could do plots – whereas I had only to find out what happened.”

Tackling the Tudors made Mantel famous after years of obscurity

For many years, Mantel wrote about “odd and marginal people”, reaching only a limited audience. But when she took on the Tudors her work exploded in popularity. As she puts it, “My readers were a small and select band, until I decided to march on to the middle ground of English history and plant a flag.”

Those who write history are caught in an impossible position between two eras

Historical novelists face an intrinsically tricky task in trying to bridge the gap between past and present while maintaining authenticity. Mantel says, “The writer of history is a walking anachronism, a displaced person, using today’s techniques to try to know things about yesterday that yesterday didn’t know itself.”

History is only ever the best we can do based on the evidence that is left

Mantel stresses that history is always imperfect. While there may be some facts and figures from the past that we know to be indisputably accurate, there will also always be many more gaps, errors and unreliable witnesses. Mantel says history is “what’s left in the sieve when the centuries have run through it – a few stones, scraps of writing, scraps of cloth.”

‘As soon as we die we enter into fiction’

Hilary Mantel argues that once we cannot speak, it is up to others to interpret us.

Historical fiction seeks out the thoughts and feelings behind the facts

While history tells us what characters did, Mantel is concerned with what they think and feel – “the interior drama of my characters’ lives.” Some critics see historical fiction as a falsification of the past. But Mantel argues that by choosing historical fiction, readers are “actively requesting a subjective interpretation” of the evidence. The writer’s job is “to recreate the texture of lived experience: to activate the senses, and to deepen the reader’s engagement through feeling.”

To imagine the past we need to recalibrate our senses and alter our assumptions

Our image of a squalid, filthy, disease-ridden past isn’t entirely accurate. Life was precarious, childbirth was dangerous and epidemics did kill, but people wore freshly washed linen, observed complex table manners, associated dirt with disease and managed to retain most of their teeth. In the pre-industrial era, the air even smelled sweeter and sounded quieter. Mantel says, “When we imagine a lost world, we must first rearrange our senses – listen and look, before judging.”

The Tudor period offers rare opportunities for writers to focus on women

In general, women are pushed to the edges of history. When writing about Henry VIII, however, Mantel describes her “particular joy” that here “the women are real players. Catherine of Aragon [and] Anne Boleyn are two of the most intelligent and astute and shrewd politicians in Europe.”

Truth is important, but a writer must be pragmatic too

Mantel presents the Polish writer Stanisława (or Stasia) Przybyszewska as an example of how the search for truth can destroy a writer. Working in the first half of the twentieth century, Stasia’s obsession with accurately documenting the French Revolution led to her spending the final seven years of her life writing alone in a single room, with little food, money, or even daylight, and dying alone at the age of 34. Mantel says Stasia “worked and worked to get the truth”, but “was crippled by perfectionism” producing exceptionally detailed unfinished novels, and vast plays that were too long to be performed.

An obsession with history killed a young Polish writer

Hilary Mantel claims a piece of literature can have a damaging hold over its author.

Artists are caught between the need to create and the desire to absorb

Mantel describes the tension artists experience between their inner creative lives and their engagement with the world beyond. She says, “You want to be at your desk or in your studio, mining your resources, but you also want to be out there in the world, listening and looking to replenish your talent. There’s no safe point, no stasis.”

Every page in a novel is a result of hundreds of tiny choices, both linguistic and imaginative, made word by word, syllable by syllable.

The challenge of historical fiction is deciding what to leave out

Writers of historical fiction “need to know ten times as much” as they will ever tell. When deciding what to include, Mantel says, “You are looking for the one detail that lights up the page: one line, to perturb or challenge the reader, make him feel acknowledged, and yet estranged.”

Knowing the ending doesn’t hinder an audience’s enjoyment – it heightens it

Mantel believes that a reader’s knowledge of what is coming can heighten the drama, since it puts them in two places at once: “He is at the foot of the cliff, wise after the event, and he is also on the path, he is before the event; he is the observer, and he is also the person who steps into air.”

Stage plays can bring history to life in the moment and make it interactive

Mantel says, “A stage play is a brilliant vehicle for the past, because it is a hazardous, unstable form, enacting history as it was made – breath by breath.” The script provides the boundaries within which the story unfolds, but the actors – and the audience’s reactions to them – create a new interpretation each night.

History does not repeat itself

Hilary Mantel says history is never repeated. But, it can be lived again through art.

History doesn’t repeat itself, except through art

Mantel says, “I don’t believe history ever repeats itself, either as tragedy or farce. I think it’s a live show and you get one chance. Blink and you miss it. Only through art can you live it again.”

About Dame Hilary Mantel

Dame Hilary Mantel (1952-2022) was an English writer whose work included personal memoirs, short stories and historical fiction. She wrote 14 novels and was a two-time winner of the Man Booker Prize for her bestselling novels, Wolf Hall, and its sequel, Bring Up The Bodies.

Notable works

- Fludd: Viking, 1989

- A Place of Greater Safety: Viking, 1992 (Memoir)

- Giving Up the Ghost: Fourth Estate, 2003

- Beyond Black: Fourth Estate, 2005

- Wolf Hall: Fourth Estate, 2009

- Bring Up the Bodies: Fourth Estate, 2012

The 2017 BBC Reith Lectures

![]()

The Reith Lectures: Hilary Mantel

Novelist Dame Hilary Mantel discusses the role that history plays in our culture.

![]()

Download the podcast

Significant international thinkers deliver the BBC's flagship lecture series.

![]()

Find out more

Discover more about the history of The Reith Lectures.