Nine things we learned from Sir Salman Rushdie’s Desert Island Discs

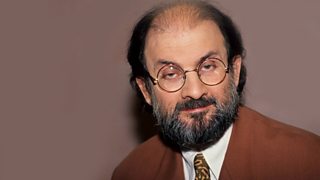

Sir Salman Rushdie’s life has been just as dramatic as his fiction: a childhood in Bombay, a fatwa that forced him into hiding in the late 1980s, and a near-fatal attack decades later. Through it all, he kept writing and kept his optimism.

On his second appearance as a castaway, he reflects on family, survival, and the stories that shaped him.

Here are nine things we learned from his Desert Island Discs…

![]()

Listen to Sir Salman Rushdie’s Desert Island Discs

Listen on BBC Sounds to hear the episode with full music tracks first.

1. His parents taught him about storytelling

Salman has fond memories of growing up in Mumbai [formerly Bombay], he tells presenter Lauren Laverne, like eating coconuts and having camel races with his sister on Juhu Beach.

As a child, he learned the art of storytelling from his parents. His father would tell him bedtime stories – “His version of the great storehouse of fantastic tales: the animal stories of the Panchatantra, the epics of the Mahabharata and Ramayana, and the tales of the fantastic like the Thousand and One Nights” – and his mother would share all the local gossip. “She knew where all the bodies were buried. At a certain point she said she was going to stop telling me things because I put them in my books and she gets in trouble!”

Did she stop? “Nope. She couldn’t help herself.”

2. His first fictions were the letters he sent home from boarding school

At the age of 12, Salman moved to the UK to attend boarding school, following “some spirit of adventure, I guess. I remember reading the Swallows and Amazons books. The amount of personal freedom those children had, I thought it was sensational.”

My first fictions were my letters home. I would say, ‘I had a great game of cricket today. Scored 23 not out, took two slip catches.’ All complete nonsense.”Salman Rushdie on hiding his experiences from his parents

But it was a difficult transition. “It was January of 1961, and I came from the tropics. It was shockingly cold. And there was a certain amount of racial prejudice that I was a victim of.”

He didn’t tell his parents about the racism he experienced. “I thought, my parents have made all these sacrifices. So, my first fictions were my letters home. I would say, ‘I had a great game of cricket today. Scored 23 not out, took two slip catches.’ All complete nonsense.”

3. Bob Dylan was a revelation

One of Salman’s classmates had a record player and a copy of The Freewheelin’ Bob Dylan. “He said, ‘Come in here and listen to this.’ I listened to a track or two and I wanted to speak and he said, ‘No you can't say anything until you've listened to the whole thing!’ So, he made me listen to the whole album, and I was blown away. I started speaking and he said, ‘No, you have to listen to it all again.’ So, we listened to the whole album twice and then I was allowed to say that I liked it.”

He chooses Blowin’ in the Wind as his third disc, and years later saw Dylan performing the track at Madison Square Garden. “He screamed it like a punk song. It made you understand it’s actually a very angry song.”

4. He turned into a 'thief' for a newspaper story

At Cambridge University, Salman wrote for the student paper, reporting on a spate of thefts from student rooms. Wanting to emulate the journalists he admired, he decided: “Be the thief. So, I chose half a dozen staircases, knocked on doors, and if nobody answered, I saw if the door was unlocked. If it was, I went in and made a list of what I could steal.”

I needed to feel optimistic myself. And I have to say the book written in maybe the darkest moment of my life has been one of the most joyful experiences in terms of its life in the world.”Sir Salman Rushdie on writing Haroun and the Sea of Stories

Although he never actually stole anything, unfortunately for Salman, one of the unlocked rooms belonged to the editor of the paper. “It had a lot of very expensive stuff. To his credit, he ran the article. But he never hired me again.”

5. Literary success was not immediate

It took 13 years for Salman to become established as a successful author. After graduating from Cambridge in 1968, he worked in advertising. His first book, Grimus, was published in 1975 and had “a poor reception – to put it mildly”.

But in 1981 came Midnight’s Children, which won the Booker Prize and has since been voted the best novel of all Booker winners. His fortieth birthday party in 1987 felt like a climax, and he picks Whitney Houston’s I Wanna Dance with Somebody (Who Loves Me) as his fifth disc to remind him of that celebration. “I’d had a very good decade. I didn’t realise that 1988 was going to descend like a hammer.”

6. His next book changed everything

After The Satanic Verses was published in 1988, a fatwa calling for Salman’s death was issued by the supreme leader of Iran. He hadn’t expected the storm. “It was treated as if it was nonfiction. I thought probably some people might not care for it. But I thought, ‘You don’t have to read it.’ That’s why there are lots of books in bookstores. You can read the ones you like.”

Salman had to leave his home and was under security protection for a long time. “If you had told me on that day, listening to Whitney, ‘Here's what's going to happen to you, how do you think you'll handle it?’ I would not have bet on myself to handle it well. I would never describe myself as tough, but some bit of me obviously is.”

7. A promise to his son saved him

After being forced into hiding, he found his attitude to the situation changing. “What, I’m hiding behind the sofa?”, he remembers thinking, “that’s not very heroic. I think the thing that rescued me was work. I thought the only thing I can do is to go on being the writer that I'd always set out to be.”

Besides, he’d made a promise to his son to write a book that he’d enjoy reading. “If you make a promise to a child, you should probably keep it. So, I wrote Haroun and the Sea of Stories.” It's a very optimistic book, he explains. “I think maybe I needed to feel optimistic myself. And I have to say the book written in maybe the darkest moment of my life has been one of the most joyful experiences in terms of its life in the world.”

8. Coming out of hiding meant hailing a taxi

Years later, when the threat level against Rushdie had changed, the security protection was dropped. “They got up and shook hands and walked out of the room. Boom! Like that. I thought, ‘Oh, I’d better get a taxi.’ I hadn’t got a taxi in eight and a half years.”

The sudden freedom was strange: “Human beings' desire for normality is so great that when you get it, you just go for it in a big way.” He wanted to show people he wasn’t scared. “If they see, ‘Oh, he’s walking around taking the subway’, they relax.”

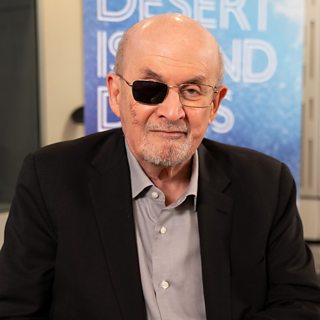

9. An attempt on his life taught him what was valuable

In 2022, he was stabbed on stage in New York. “I just thought, 'Why now?' This is three decades later.” He lost his right eye, and his left hand was badly injured, but his medical teams were amazed at his resilience and recovery. “Again, apparently, I'm tougher than I thought. I was absolutely determined to get my life back. I thought, ‘Hell with this, I’m not letting this stop me.’”

What did it teach him? “When you have a lucky escape like this, you begin to value everything more: the days, love, your work. It puts into enormous relief the important things in life and makes you understand there are many things which are not important, and you can do without.”