Five Things I Learned about Morality in the 21st Century

In his Radio 4 series, Morality in the 21st Century, Rabbi Lord Jonathan Sacks speaks to some of the world's leading thinkers, together with voices from the next generation: groups of British Sixth form students. This is what he learned.

The five-part series on Morality in the 21st Century is, for me, the culmination of a 50-year journey which began when I was an undergraduate at Cambridge. I was studying philosophy, which in those days was called "Moral Sciences." I quickly discovered that this was a huge misnomer. The logical positivists had in effect declared that if it’s scientific, it isn’t moral, and if it’s moral, it isn’t scientific.

Morality, in their view, turned out to be no more than a matter of intuition, or emotion, or subjective choice. One book from around that time was entitled, Ethics: Inventing Right and Wrong.

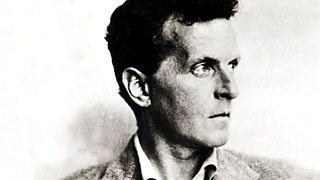

This was most peculiar. The Austrian-British philosopher Ludwig Wittgenstein, my then hero, had argued that there can be no such thing as a private language. Or to give a simpler example: there can be no such thing as a game of football for one. Morality, like language and football, is a social practice. It is the set of values, virtues, customs and codes, that create and sustain communities. It is what turns a group of disconnected “I”s into a collective “We.”

So the idea that morality is whatever we privately choose, or feel, or intuit it to be, struck me as nonsensical. But that didn’t stop societies throughout the West from adopting that view at roughly that time.

Morality in Britain and America ceased being a society-wide code. Instead, we outsourced it to the market and the state. The market gave us choices. The state dealt with the consequences of those choices. As for the rest of our lives, that was up to us. Whatever works for you, so long as you don’t directly harm others.

Rabbi Lord Jonathan Sacks

An international religious leader, philosopher, award-winning author and respected moral voice, Rabbi Lord Jonathan Sacks was awarded the 2016 Templeton Prize in recognition of his “exceptional contributions to affirming life’s spiritual dimension.” Described by HRH The Prince of Wales as “a light unto this nation” and by former British Prime Minister Tony Blair as “an intellectual giant”, Rabbi Sacks is a frequent and sought-after contributor to radio, television and the press both in Britain and around the world.

Since stepping down as the Chief Rabbi of the United Hebrew Congregations of the Commonwealth – a position he served for 22 years between 1991 and 2013 – Rabbi Sacks has held a number of professorships at several academic institutions including Yeshiva University and King’s College London. In addition to his writing and lecturing, he currently serves as the Ingeborg and Ira Rennert Global Distinguished Professor at New York University. Rabbi Sacks has been awarded 17 honorary doctorates including a Doctor of Divinity conferred to mark his first ten years in office as Chief Rabbi, by the then Archbishop of Canterbury, Lord Carey.

Rabbi Sacks is the author of over 30 books. In recognition of his work, recent awards to Rabbi Sacks have included The Becket Fund’s 2014 Canterbury Medal for his role in the defence of religious liberty in the public square; a Bradley Prize in 2016 in recognition of being “a leading moral voice in today’s world”; and in 2017, he was awarded the Irving Kristol Award from the American Enterprise Institute for his “remarkable contributions to philosophy, religion, and interfaith discourse… as one of the world’s greatest living public intellectuals.” In 2018, he was given the Lifetime Achievement Award by The London Jewish News in recognition of his services to the Jewish world and wider society.

I wanted to know where that road led, 50 years on. What I discovered in the course of the conversations that make up the series was:

Morality ceased being a society-wide code. Instead, we outsourced it to the market and the state.

1. Trust in corporations and governments has plummeted. Only 6 percent of young people today trust corporations to do the right thing, down from 60 percent a generation ago.

2. Smartphones and social media are becoming addictive and having a bad effect on teenagers (and adults too), who are spending between seven and nine hours a day looking at a screen. The longer you spend on social media, the more miserable you become.

3. We’ve moved, in Britain and America, from being a “We” society – “We’re all in this together” – to an “I” society: “I’m free to be whatever I choose.” The bad news is that this leaves people vulnerable and alone. The good news is that we can turn it around and become a “We” society again. It happened a century ago, between 1910 and 1950.

4. By taking responsibility and refusing to see ourselves as victims we can triumph over fate. And by changing one life for the better we can find meaning and fulfilment in our lives.

5. The ten intellectuals and two philanthropists I spoke to are all, in their individual ways, articulate visionaries of a remoralised society. The best news of all, though, is that the stars of the series are the schoolchildren. They enriched every episode. They are the face of our future, and they have the energy, intelligence and passion to make society a more moral place, one to which we will feel proud to belong.

Listen to Morality in the 21st Century on BBC Radio 4, and download extra features from the Podcast series.

Morality and Ethics on Radio 4

![]()

Morality in the 21st Century

Rabbi Lord Jonathan Sacks explores what morality means in the 21st Century with some of the world's leading thinkers, and groups of British Sixth form students.

![]()

Reith Lectures 1990: The Persistence of Faith

Jonathan Sacks delivers six Reith Lectures examining Religion and Ethics in a secular society.

![]()

Moral Maze

Combative, provocative and engaging live debate examining the moral issues behind one of the week's news stories.