Conceptual Art in Britain: Radical or rubbish?

12 April 2016

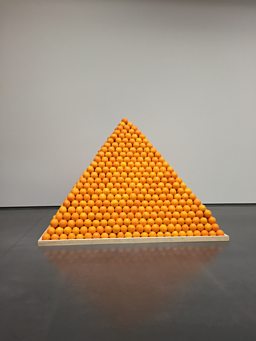

Glasses of water masquerading as trees, a stack of oranges and a pile of sand are just a few of the exhibits to be found in Conceptual Art in Britain 1964 – 1979, a new exhibition at Tate Britain. The show explores the work of the British artists who challenged the very idea of what art could be. Whether lauded for being ground-breaking or condemned for being trivial, Conceptual Art has provoked strong reactions. WILLIAM COOK explores the legacy of a contentious and playful chapter of British art.

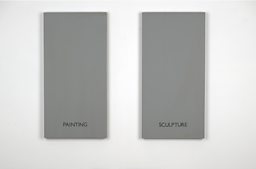

In the 1960s and 1970s something very odd happened to Modern Art. A lot of artists turned away from conventional sculpture and painting.

Instead, they started creating strange new objects which challenged our basic assumptions about the meaning and the role of art.

What constitutes an artwork? Is a filing cabinet full of blank postcards art? How about a bag of rubbish?

What constitutes an artwork? Is a filing cabinet full of blank postcards art? How about a bag of rubbish? Or a heap of sand?

Suddenly, art was no longer confined to the plinth, the canvas, or the gallery. It could be anything you wanted – or nothing at all.

This was the essence of Conceptual Art, a radical movement which shook up the art world fifty years ago.

Conceptual Art in Britain 1964-1979 focuses on its UK pioneers.

It isn’t comprehensive - Conceptual Art was just as big in mainland Europe and America - but it gives you a good idea of what made these artists special, and how revolutionary they once seemed.

‘Conceptual Art marked a complete and utter break with orthodox traditions,’ says Andrew Wilson, the curator of this intriguing show.

Unlike conventional artists, Conceptual Artists made you use your imagination. They only gave you the bare bones - it was up to you to invent the rest.

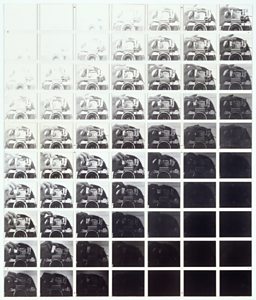

‘The content of this painting is invisible,’ declared the avant-garde ensemble Art & Language. ‘The character and dimension of the content are to be kept permanently secret, known only to the artist.’

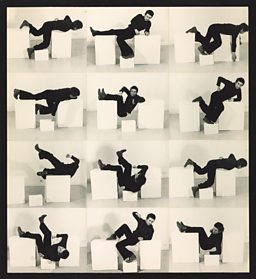

Were they joking? It’s hard to tell. For Conceptual Artists, the process of making a work of art was more important than the end result.

For the most part, Conceptual Art was full of fun

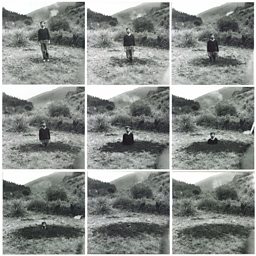

Hamish Fulton hitchhiked from London to Andorra, and typed up a list of all the people who gave him lifts along the way. Is this list a work of art, or was his journey the real artwork?

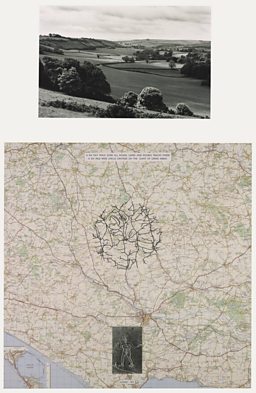

The finest practitioner of this form was (and still is) Richard Long – the only artist in this group show who’s become something like a household name.

Long was at art school with Fulton, and they went to South America together.

For Long, like Fulton, the journey was also paramount, but Long’s records of his epic trips have a lyrical resonance which sets them apart.

His Hundred Mile Walk (in a perfect circle around windswept Dartmoor) is enhanced by snatches of succinct poetry. ‘Day One: winter skyline, a north wind.

Day Two: the earth turns effortless under my feet. Day Three: suck icicles from the grass stems. Day Four: as though I had never been born.’

At its worst, Conceptual Art could be terribly po-faced. Often it wasn’t the actual artworks which were exasperating, so much as the artists’ convoluted explanations.

Bob Law’s black canvas is a standard example of minimalism - it’s his long-winded commentary, reproduced alongside it, which makes it seem pretentious.

Display cabinets full of wordy essays show there are few things more tedious than artists talking about art. But, for the most part, Conceptual Art was full of fun.

Braco Dimitrijevic (a Yugoslavian based in London) took a snapshot of an anonymous passer-by and pasted it onto a double-decker bus.

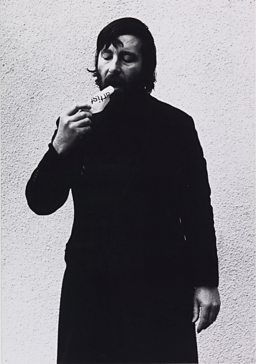

Keith Arnatt produced a series of photographs in which he (literally) ate his own words.

Art that challenges

‘I have decided to go to the Tate Gallery next Friday,’ announced Arnatt. ‘The above statement is operative as “artwork.”

Like Dada, Conceptual Art was more of an attitude than a genre

Though Conceptual Art seemed new, these pranks harked back to Dada. No wonder the show’s curator, Andrew Wilson, calls Marcel Duchamp ‘the grandfather of Conceptual Art.’

This chronological survey starts when Labour leader Harold Wilson became Prime Minister, in 1964. It finishes when the Conservative leader Margaret Thatcher took over, in 1979.

Of course these historical bookends are a bit arbitrary (Conceptual Art didn’t begin the day Wilson became PM, or end when Mrs Thatcher moved into Number Ten) but it’s true that most of what we call Conceptual Art happened within these fifteen years, an era when the younger generation became increasingly influential, and old certainties were overturned – not only in the arts, but within society at large.

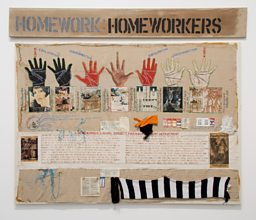

There’s a big divide between the two decades.

The Sixties exhibits are more abstract, more philosophical, more optimistic. The Seventies exhibits are more explicit, more politically engaged: Margaret Harrison’s collage highlights the exploitative injustice of homeworking; Conrad Atkinson chronicles Northern Ireland’s Troubles through sectarian soundbites from both sides of the divide.

Victor Burgin reproduces a headline from The Economist which defined the zeitgeist: ‘7% of our population own 84% of our wealth.’

Like Dada, Conceptual Art was more of an attitude than a genre. Like Dada, it didn’t last but its influence endures.

Today we take it for granted that an artwork can be almost anything. The fact that we think that way is thanks to these Conceptual Artists.

‘It’s like walking out of one room marked Modern Art and into another roomed marked Contemporary Art,’ says Andrew Wilson. ‘The door you’ve walked through is called Conceptual Art.’

![]()

Free Thinking | BBC Radio 3

Philip Dodd is joined by artist Bruce McLean and critic Sarah Kent to consider the British Conceptual Art show at Tate Britain.

Related Links

Conceptual Art in Britain 1964-1979 is at Tate Britain until 29 August 2016.

More from BBC Arts

![]()

Picasso’s ex-factor

Who are the six women who shaped his life and work?

![]()

Quiz: Picasso or pixel?

Can you separate the AI fakes from genuine paintings by Pablo Picasso?

![]()

Frida: Fiery, fierce and passionate

The extraordinary life of Mexican artist Frida Kahlo, in her own words

![]()

Proms 2023: The best bits

From Yuja Wang to Northern Soul, handpicked stand-out moments from this year's Proms