Jean-Michel Basquiat: From homeless to $110m artist

21 September 2017

Graffiti artist. Musician. Painter. Heroin addict. Style icon. Jean-Michel Basquiat painted fast and died young, aged 27. In May 2017, the sale of one of his paintings for $110m sealed his legend. A new, noisy show of his work at London’s Barbican turns up the volume. By ALLAN CAMPBELL.

Comprising over 100 works, Basquiat: Boom for Real traces the expressionist painter’s career from graffiti artist – his adopted tag was SAMO© (Same Old Shit) – to international star, with film archive and matching soundtrack. Surprisingly, this is Basquiat’s first major British exhibition (his first UK show was at the Fruitmarket Gallery, Edinburgh, in 1984).

- Radio 4's arts strand Front Row interviewed the former director of the ICA to discuss the exhibition, and it also features later in the programme's new weekly Saturday evening foray into television on BBC Two.

Explore the story of Basquiat's career, cut short after flowering for just a decade, through the photographs and paintings below.

Basquiat on Front Row

![]()

21 September, Radio 4

Ekow Eshun considers whether Basquiat really was 'one of the most significant painters of the 20th century', as the show claims.

![]()

30 September, BBC Two

Presented by Nicola Bedi with guest Ian Hislop. Street Artist Bambi takes an out-of-hours tour of the Basquiat exhibition.

Homeless in Manhattan

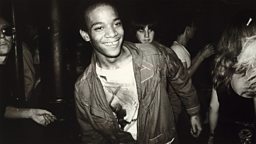

It can be hard to find photos of Basquiat smiling. But this snap at the legendary NYC club finds him on the brink of a breakthrough. As a struggling graffiti artist in the late Seventies, he was sometimes homeless, despite being from a reasonably affluent family. But his days working in a Brooklyn clothing warehouse, with some drug dealing on the side, were numbered, as his SAMO©-tagged graffiti and provocative slogans gained increasing attention.

New York Beat Movie

Basquiat made the leap into galleries as part of a well received 1980 group exhibition, Times Square Show. Now very much part of the Downtown scene, he mixed with No Wavers such as James Chance, hip-hop notable Fab Five Freddy, and Debbie Harry and Chris Stein from Blondie. When writer and scene-maker Glenn O’Brien decided to make a semi-dramatised movie of Village life, New York Beat Movie, he cast most of them and gave the lead role to Basquiat. But it would be 20 years before the film was released as Downtown 81.

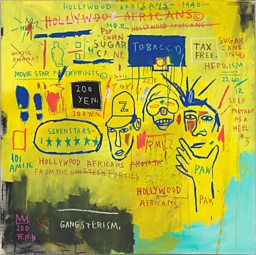

Hollywood Africans

In March ’82 Basquiat had his first, very successful, single artist exhibition at the Annina Nosei Gallery, NYC. Soon he began to pick up shows in Europe and Los Angeles. Painted while in LA, this was one of a series which dealt with African American stereotypes in the entertainment business. It mixes the historical (such as ‘Sugar Cane’) with the personal (Basquiat had produced a single for rapper Rammellzee; see central figure ‘RMLZ’).

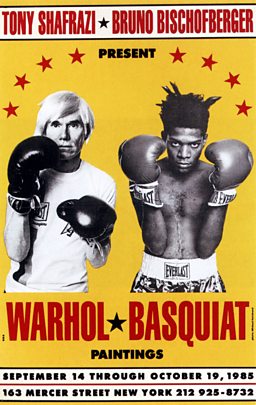

Warhol & Basquiat Vs Critics

Andy Warhol and Jean Michel Basquiat in New York exhibition poster, 1985 | Getty Images

It’s difficult to look at this poster for Andy Warhol and Jean-Michel Basquiat’s 1985 joint show and not consider the possibility that ‘Drella’ is rejuvenating himself on young blood, while Basquiat is looking to elevate himself to the upper reaches of the art establishment by association. Critics tore the exhibition apart. Depressed at the reaction and increasingly dependent on heroin, the experience hastened Basquiat’s downward spiral. He would die in his Manhattan studio of a drug overdose in 1988.

The $110m post script

“I am happy to announce that I just won this masterpiece,” began Yusaku Maezawa’s Instagram post of 19 May, 2017. The accompanying photos show the Japanese entrepreneur standing next to his acquisition, Basquiat’s Untitled (1982), which he had just purchased at auction at Sotheby’s New York for $110.5m, a record for a US artist. Three years before his death, Basquiat’s father Gérard asked the unhappy painter why he was so tense, when he had everything. His son replied that only one thing worried him - “Longevity”. It would seem that Basquiat has that now.

Basquiat: Boom for Real

The title, King Zulu, refers to jazz musician Louis Armstrong’s honorary New Orleans title as leader of the city’s carnival group, the Zulu Aid and Pleasure Club, a title he valued. The painting has an ambivalence as it shows Armstrong, an African American, in traditional blackface.

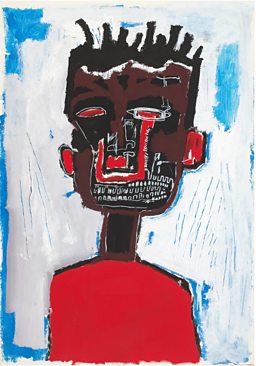

In Self Portrait (1984), Basquiat puts identity front and centre, drawing attention to his African American lineage. He maintained that he rarely painted self-portraits but much of his work refers to self, if sometimes obliquely.

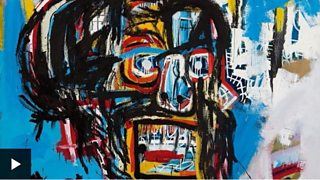

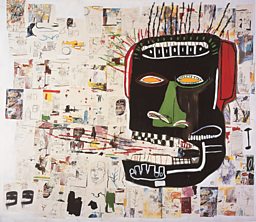

The subject of this painting is probably journalist Glenn O’ Brien but it obviously doesn’t represent him. The style is classic Basquiat; it’s likely inspired by a Haitian mask (suggesting his own background) with energetic paint work and collage made up of pages from his notebook.

Basquiat: Boom for Real is at the Barbican, London, until 28 January, 2018.

Basquiat at the BBC

![]()

Radio 3's Late Junction celebrates Basquiat

Max Reinhardt explores Basquiat's musical inspirations and collaborations.

![]()

Jean-Michel Basquiat: The neglected genius

Friend to the artist Jennifer Stein on how Basquiat wasn't properly looked after by those around him.

![]()

'He was the man' - young artists on Basquiat

As a major exhibition of his work opens in London, young black artists celebrate Jean-Michel Basquiat's impact on art.

More from BBC Arts

![]()

Picasso’s ex-factor

Who are the six women who shaped his life and work?

![]()

Quiz: Picasso or pixel?

Can you separate the AI fakes from genuine paintings by Pablo Picasso?

![]()

Frida: Fiery, fierce and passionate

The extraordinary life of Mexican artist Frida Kahlo, in her own words

![]()

Proms 2023: The best bits

From Yuja Wang to Northern Soul, handpicked stand-out moments from this year's Proms