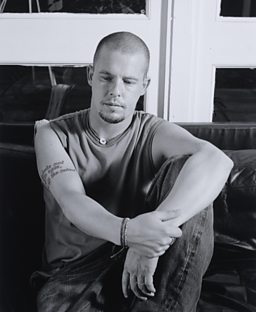

Alexander McQueen: From 'pink sheep' to top dog

11 March 2015

Alexander McQueen: Savage Beauty - a retrospective of the work of the late fashion designer - opens at London's V&A this weekend. Originally conceived by the Costume Institute at the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York, where it enjoyed a record-breaking run in 2011, Savage Beauty has been expanded for the V&A with 30 additional garments. Paris-based fashion journalist DANA THOMAS, author of Gods and Kings: The Rise and Fall of Alexander McQueen and John Galliano, examines the life and career of one of the most innovative designers of his generation.

Alexander McQueen: Savage Beauty

A first look at the Savage Beauty exhibition. With thanks to the V&A.

When Lee Alexander McQueen died five years ago — he committed suicide at the age of 40 — fashion lost one of its greatest-ever talents.

McQueen didn't believe in frontiers. Nothing — nothing — was taboo. He accepted the brutality of human nature, thought it normal, didn't try to suppress it. He didn't want to put women on a pedestal like untouchable, unreachable goddesses. He didn't want to protect them with an armor made of cloth.

He didn't want to put women on a pedestal like untouchable, unreachable goddesses

He wanted to empower them. He wanted to help them use the power of their sex to its fullest.

This force is on display in Savage Beauty, a stunning retrospective of his work at the Victoria and Albert Museum.

The show — a remounting of the blockbuster that was first staged at the Metropolitan Museum of Art's Costume Institute in 2011 — will have more than 200 pieces, including 30 that were not on display in New York.

McQueen was raised in the East End of London, in a working class family — his father was a black cab driver.

He had a rough childhood: he was bullied for being "the pink sheep of the family", as he described it; sexually abused by a relative; watched in horror as his sister was beaten by the same man.

What saved him from a dead-end life was his creative mind, profound talent and sheer will. "I thought: 'I'm not gonna get married, live in a two-up, two-down and be a bloody black cab driver'," he said.

At 16, his mother suggested that he get a job on Savile Row as an apprentice tailor. His employers soon realised how gifted he was with a needle and thread; in a matter of a few months he mastered techniques that usually took several years of training.

Less than ten years later, he was the head of the Givenchy couture house in Paris.

As visitors will see at the V&A, his suits were sharp and precise. He made dresses of seashells he collected on beaches, of formaldehyde-preserved locusts, of shards of black resin that clicked like broken glass when the model walked.

Later, he added a touch of faded, mournful romanticism to his work

Later, he added a touch of faded, mournful romanticism to his work, decorating his gowns with full-blown flowers past their prime and basing a collection on a dance marathon, the models collapsing from exhaustion into a heap.

His greatest gift, however, was how he could take a bolt of fabric, wrap it around a woman’s body, and in a flash, there would be a dress.

His friend Cecelia Sim learned this firsthand when she asked him to make her wedding dress. The pair went down to the Indian fabric shops in the East End and bought several yards of silk in off-white and oyster.

Once back at the studio, McQueen draped the fabric on Sim, pinned it here and there, picked up his shears, and started cutting it directly on her.

"Hey!" she cried nervously. "Do you know what you're doing?"

"Yes, yes," he said, calmly. "Don’t worry."

In a couple of hours, he had created a two-tone 1930s slip dress with an asymmetrical neckline. He hand-twisted one of the two straps, and there were no hooks or zippers.

For her wrap, he crafted a cocoon coat in two layers of pale mushroom gray tulle, in between which he slipped fabric rose petals and butterflies.

"Ideas like that were getting churned out every hour or so," remembers McQueen’s former boyfriend and assistant Andrew Groves. "Everyone [else] back then was so boring and derivative. [McQueen] didn't realize what he was doing was so different."

Alexander McQueen: Savage Beauty is at the V&A, London from 14 March to 2 August 2015

'Lee' the London lad

By Michelle Olley, friend and fomer collaborator

I first met Lee when we were guests at a very different kind of event from the breathtaking McQueen couture spectacles now passed into fashion legend.

Back in 1994, Fiona Cartledge's seminal 90s street-and-clubwear emporium, Sign of the Times, was creating legends of its own, with a string of flamboyantly-themed fashion and rave mash-up club nights in London.

I met Lee at their Superheroes event at Brixton Academy. He was there with designer Andrew Groves, whose Jimmy Jumble label was stocked at Cartledge's Covent Garden store.

I remember thinking how sweet and unassuming the boy in the ancient grey sweatshirt and battered builder's jeans was. I also remember That Laugh. Right from the get go: rapid-fire gunshot delight in pure mischief.

After that, our paths crossed many times, in various London demi-mondes – I was a writer/editor/club promoter/singer during the 90s, so we had friends in common around the Soho fashion-and-nightlife axis.

It wasn't until September 2000 that I worked with 'the' Alexander McQueen – fashion master. Sign of the Times alumni Sidonie Barton had by this time become Lee's right-hand woman.

When he needed a game, plus-size model to recreate Joel Peter Witkin’s Sanitarium image for the centrepiece of his spring/summer 2001 womenswear show, Voss, she called me.

Witkin's work uses carnival folk, octogenarians, cadavers and taxidermy to recreate classic paintings and religious iconography. Santarium features a naked, obese woman on a chaise longue, in an animalistic, bewinged hood, connected to some tubes that lead to the mouth of a stuffed monkey.

"Firstly, you won’t be entirely naked..." said McQueen. True. I was to be covered in giant moths – living and dead ones.

"You’ll be inside an opaque glass box, in a hood, with breathing tubes, and at the end of the show the sides will come crashing down, the glass will smash and all the moths will fly into the audience."

My mind reeled at all this, but I already knew, as he continued to reassure me about the nudity (the least of my concerns, frankly) that I was going to say yes, precisely because it was deliriously scary. I agreed to do it on the following caveat: "I just want you to know... I’m doing it for Art."

McQueen rose from the coffee table to attend to the business of getting ready for the show in ten days time, saying: "I thought we all were."

We got on great from that moment on. There is much written about the difference between McQueen the fashion legend and 'Lee' the proper London lad. I was fortunate to see both sides.

When he was working on the show, the focus was immense – the attention to detail was applied to every aspect – from the always-confrontational higher concept right down to the 'bird droppings' painted on my rubber-cement-moulded headpiece.

He had high standards for creative people. He once lambasted me at a magazine launch party for taking a staff job on the title, saying I should be concentrating on my 'real' writing. He still turned up to support it, though.

He wasn't comfortable with being lauded in public/social situations, but that didn’t stop him from going anywhere he wanted to, often dressed down/incognito.

One of my fondest memories of him is spending a Halloween evening at Simon Drake's House of Magic – an otherworldly, down-the-rabbit-hole cabaret venue, where everything and everyone is... well, magical.

That laugh - as he delighted in the phantasmagorical-ness of it all. McQueen was never happier than when surrounded by mischief and spectacle.

Related Links

![]()

Private View: Tinie Tempah on Alexander McQueen

Musician and style icon Tinie Tempah takes us on an exclusive tour of the blockbuster exhibition at the V&A for BBC iPlayer.

From the archive

![]()

The Works: Cutting Up Rough (BBC iPlayer)

First transmitted in 1997, The Works follows Alexander McQueen at London Fashion Week.

![]()

Witness (BBC World Service)

Fashion designer Alexander McQueen shocked the world in 1995 with an outrageous collection.