Main content

Composer Portraits

Is what you see what you hear? Tom Service considers what we think composers look like in the portraiture and imagery we have of them – and how we play them, hear them, and interpret them.

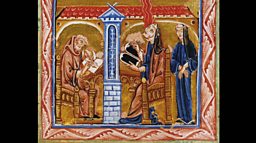

Hildegard of Bingen: 12th-century portrait

The images we have of Hildegard show her in a typical moment of ecstatic inspiration, as her transcendental visions came to her – a process of blinding, blazing intensity, as the picture shows – and as you can see, the imagery Hildegard uses appropriates that of the Pentecost to embody the moment of her divine communion: a river of flame descends from the heavens, out of the frame of the picture, and into Hildegard’s upturned eyes.

Hildegard’s portrait is a remarkable image for any time, but especially from a time in which women’s role in spiritual as well as civic society was severely limited – for Hildegard to be pictured in a moment of inspiration that only she could have (not the men around her, or anyone else, for that matter!) – is testimony to her powers of creative and theological illumination.

J S Bach: portrait by Elias Gottlob Haußmann (1748)

This is Bach at the age of 62, in his periwigged pomp: his look is quizzically stentorian – a slight frown, his head slightly turned so that he seems to asking something of us, his audiences. In infinite reproductions, this picture – and another version of the same image that Hausmann made in 1748, which belonged to Bach’s son, Carl Philipp Emmanuel – have become the most important elements of Bachian iconography. I think the way we interpret and perform Bach is in this picture, too: we can read changes in performance practice along with a deepening understanding of the man in the portrait.

It’s all a matter of different ways of seeing. If we see Bach as a stern musical law-giver – one possibility you can definitely read into this image! – you’ll think of Bach and his music as a kind of musical scripture that is to be revered, treated as gospel, and performed with a requisite spirit of humility, self-abasement, and austerity.

But there’s even more in this portrait, because it’s also a picture of Bach’s music – literally. Bach’s left eye, slightly in shadow, has a glint of – well, not quite humour, but something scurrilous in it; the kind of look someone gives you when they’re about to tell you a secret – or challenge you with a riddle.

And that’s what Bach’s right hand, at the bottom of the picture, is offering us. It’s three lines of music: when you first see them, you probably think they’re there as a symbol of the fact that this man's a composer, so he’s holding a bit of manuscript, and the painter will have come up with some random quasi-musical jottings just to confirm the symbology of composition.

But this is more than a painterly suggestion: it’s a real piece of music, by Bach, that Haußmann has faithfully made part of the picture. In fact, what Bach is offering us is a self-contained compositional kit of unbelievable sophistication. It’s called, “canon triplex a 6 voc" – a triple canon in six voices, one of those pieces where you play the same or similar music at slightly different time – an advanced version of Frere Jacques. The meaning of Bach’s quizzical glint is revealed in this painted canon – he’s challenging us: go on, solve this – if you can and if you dare!

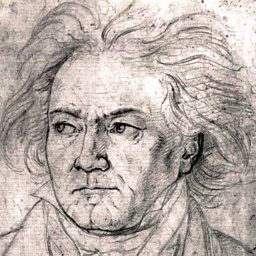

Ludwig van Beethoven: from-life sketch by Carl August von Kloeber (1818)

Here, we’re looking at the epicentre of classical music portraiture: my favourite image of Beethoven, a from-life sketch by Carl August von Kloeber. It was made in 1818, the year Beethoven wrote the pianistically impossible and impossibly pianistic Hammerklavier Sonata: music that tears at the limits of what the early 19th century keyboard – and every piano ever since! – can do.

This picture is a likeness that Beethoven himself was happy with, especially his hair. No surprise: it’s a tumult of creative chaos, a maelstrom of a hirsute halo that only adds to the impression of untameable Romantic genius and individuality: he’s looking to his right, eyes raised on some distant object of musical transcendence that only he can perceive and bring to us through his music.

This portrait also cements the cultural link between crazy hair and transcendent genius – every photo of Albert Einstein is a successor of this picture! – and yet, there’s something else here: for all its hairy myth-making, this isn’t a hagiography. Maybe it’s because of the quick pencil strokes, the sense that this picture was made in Beethoven’s presence, but there’s a flesh-and blood quality to this image of Beethoven. Kloeber hasn’t shied away from the wrinkles, the furrowed brow, the cleft chin, the lines round the thin-lipped mouth. It has the same rough, unpredictable realism of Beethoven’s craggiest musical utterances.

The Listening Service – What you see is what you hear? is broadcast on BBC Radio 3 at 5pm on Sunday 10 June 2018. You can download every episode of The Listening Service here.

Composers on Radio 3

![]()

Hildegard of Bingen

Read more on the German Benedictine abbess, writer, composer, philosopher, Christian mystic, visionary, and polymath.

![]()

J S Bach

Donald Macleod explores the life and work of Johann Sebastian Bach.

![]()

Beethoven

Composer of the Week – the life and work of Ludwig van Beethoven

![]()

The Listening Service

An odyssey through the musical universe, presented by Tom Service.