The Glory of Gothic: Dan Cruickshank on the presenters who got medieval

30 October 2014

Flying buttresses, vaulted ceilings, majestic interiors... architectural historians love a bit of gothic, or the 'modern style' as it was known back in the 12th century. Here, broadcaster and art historian DAN CRUICKSHANK explores the beauty of gothic architecture by touring 40 years of screen history.

Art and architecture was brought into our homes over the years by men such as Kenneth Clark, Nikolaus Pevsner, Alec Clifton-Taylor, Jon Cannon... and Dan himself.

In this two-part feature, we meet these five faces at various masterpieces of gothic architecture. Click here to read part two.

The first instalment features Kenneth Clark's monumental all-colour Civilisation, "a marvellous window into a lost world of television"; in Umbria, Italy, Dan visits spectacular Durham Cathedral; and "much-loved, old-world" Alec Clifton-Taylor describes St John's church in Cirencester.

Dan looks back at gothic screen history and along the way presents his own love of gothic architecture, its history and techniques.

More Gothic on the BBC

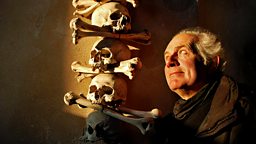

Kenneth Clark at the Basilica of St Francis, Assisi, Italy: Civilisation, 1969

This film is a marvellous window into a lost world of television.

Lord Clark is urbane and poised; suited and with that strange fixed smile that transcends emotion, words or location. The well-honed phrases are delivered with an air of utter command and – apparently – total relaxation.

Patrician is the word often used to describe Clark's performance. It is, but there was more than mere aloof style to his presentation. When the series was filmed in the late 1960s Clark was the authority on the subject – which was essentially Western Civilisation of the Christian era rather than civilisation in its broadest meaning - and his presentation remains magisterial and convincing.

Rather than trying to grab the viewer's attention through an array of gimmicks, 'eccentricities' or naughty behaviour – as has become the standard presenter style – Clark simply offers knowledge and erudite perception, delivered with an effortless drawl.

Unlike many presenters now – supported by the efforts of numerous researchers – Clark was able to write his own scripts because he knew what he was talking about, and had the knack for making facts sound conversational.

The camerawork is also without gimmicks – and superlative. It is slow, majestic, sweeping and sedate – with long periods in the film when nothing is said, leaving the camera to linger without guilt or distraction on scenes of ancient or intense beauty. The fact that all was filmed in colour – a novelty at the time for BBC programmes – would itself have grabbed and held viewer interest.

The sequence on the Basilica of St Francis at Assisi is a fine example of the series' style. The light is beautiful. The camera pans across the Umbrian landscape and sitting within dappled light is Clark who, in a most relaxed and reassuring manner, starts his informal lecture.

He does not attempt to 'discover' his subject matter with his viewers but quietly and gently tells them the way it is, making his opinions synonymous with absolute fact.

Clark does not attempt to 'discover' his subject matter with his viewers but quietly and gently tells them the way it is

At Assisi he does little more than observe that St Francis's Basilica and monastic buildings are masterpieces of the Gothic and of engineering, that the church is 13th century work and one of the "richest and most evocative … in Italy". But it is enough. We are happy, soothed. We no longer have to puzzle or wonder which is the "richest and most evocative" church in Italy. Lord Clark has told us. He has ruled. We enjoy.

Clark's lack of direct physical engagement with the building he describes is startling by current standards. He is distant from the church and does not make an appearance inside or describe its scheme of decoration. But the wonderful camera work serves him well.

The lens caresses the visually powerful, arcaded exterior and, inside, moves slowly and lovingly across the richly frescoed walls and vaults. It works. The sequence tantalises rather than informs, but more to the point it delights.

But now all this possesses an additional haunting quality. In 1997, 30 years after Clark extolled the Basilica, it was severely damaged by a vicious earthquake that tumbled walls and fractured frescoes by outstanding artists - perhaps even including Giotto.

So what we see in this film really is a lost world. Restoration has been slow and painstaking but the Basilica can never be quite the same; the authentic medieval building in which Clark gloried and that is captured by this film is, in a sense, no more.

More Kenneth Clark

![]()

Civilisation

Kenneth Clark's landmark series tracing the development of civilisation.

![]()

Constable and Wordsworth

Kenneth Clark explores Wordsworth's kinship with Constable and their common passion for nature.

![]()

Hogarth's Seedy London

Sir Kenneth Clark on William Hogarth's gift of narrative invention for 18th century London.

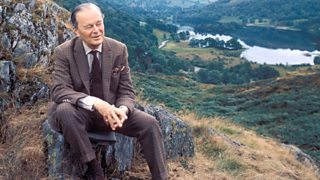

Dan Cruickshank on Durham Cathedral: Britain's Best Buildings, 2003

Making this programme was a revelation. The vast and heroic reconstruction of Durham Cathedral started in 1093 and it is famed as a late and superlative Romanesque building.

It is also renowned for its enigmatic decorative motifs – notably the abstract pattern, including chevrons and spirals, that embellish the columns of the transepts and naves.

I investigated the origins of these designs, their methods of execution and meaning, which led me to explore the range of sacred geometry that was used to define the form of the cathedral, to relate it to its monastic buildings and to imbue it with Christian qualities.

This was heady stuff, revealing the extent to which the Bible and its references to primal sacred buildings, such as Solomon's Temple in Jerusalem, were used as a design guide by cathedral builders.

It also revealed the way in which great cathedrals were created, and used before the Reformation, as stages for the theatre of Christian festival and rituals. Easter was particularly important at Durham, where a huge Paschal candle was erected in the choir and reached as high as the stone vault.

I also discovered that during the construction of Durham's choir, transepts and nave, in the first few years of the 12th century, the Gothic system of construction started to merge – perhaps evolve – with the late Romanesque tradition. To a surprising degree Durham is structurally pioneering and anticipates the fully-formed Gothic of the later 12th and early 13th centuries.

This was heady stuff, revealing the extent to which the Bible was used as a design guide by cathedral builders

As was usual with cathedral construction, work started at the east end so the choir and high altar could be completed as quickly as possible and the cathedral used for worship.

The choir is a typical piece of Romanesque architecture with walls – thick and pierced with relatively small round-arched windows – designed to carry most of the weight and restrain the outward thrust of the stone vault.

This vault was started in around 1100. It is a groin vault, which means it is formed of two semi-circular vaults intersecting at right angles to each other. The divisions between the bays of the vault are marked by semi-circular stone ribs but – new for England at the time – the vaults are also stiffened by diagonally placed transverse ribs. These gathered much of the outward thrust of the vault and took it to areas of the walls reinforced by stout, buttress-like pilasters.

Although pointed arches were not used, the structural principle of the pointed arch was achieved by the diagonal stone ribs and the Gothic system of a skeletal structure – formed by ribs, piers and buttresses – was clearly starting to emerge, well before the conventional 'birth' of the Gothic system of construction in 1144 with the choir of St Denis, Paris.

The choir vault was replaced a hundred years after construction, which leaves the north transept vault – completed in about 1110 – as the earliest high-level vault in Britain.

The pioneering Gothic spirit of the cathedral took more tangible expression in 1128 when the nave vault was started. It incorporates pointed transverse arches that permit a more finely engineered and poised structure that, using rudimentary flying buttresses concealed in the triforium, allowed the outer walls - relieved of a large part of their structural role - to be pierced with large windows to let God's light flood inside.

More Dan Cruickshank

![]()

The Family That Built Gothic Britain

The triumphant and tragic story of the greatest architectural dynasty of the 19th century. Dan Cruickshank charts the rise of Sir George Gilbert Scott, the fall of his son George Junior and the rise again of his grandson Giles.

![]()

The Bridges That Built London

Dan Cruickshank explores the mysteries and secrets of the bridges that have made London what it is; in this clip the history of Westminster Bridge.

![]()

Majesty and Mortar: Britain's Great Palaces

From the Tower of London to Buckingham Palace, Dan Cruickshank tells the story of a thousand years of palace building.

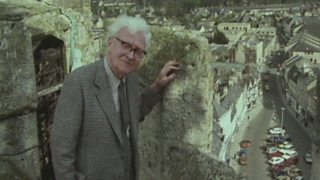

Alec Clifton-Taylor on St John’s Church, Cirencester: Six English Towns, 1984

This is vintage Clifton-Taylor. An architectural historian with a passion for England's building materials – who was discovered late in life by television but quickly became much-loved as a distinct, if old world, character.

He speaks with such profound and informed conviction (and with a touch of mischievous relish) that it seems an indisputable fact

His first series of Six English Towns was broadcast in 1977 when Clifton-Taylor was 70 years old. He gained something of a cult following, with his fruity vowels and trenchant opinions that led him to offer informed but often pungent – if not withering - observations on many of the nation's much-loved historic buildings.

Clifton-Taylor represented an admirable BBC convention that started to be questioned and eroded during the 1970s and '80s. In the early days of television specialist subjects like architecture tended to presented by established and informed experts like Lord Clark.

Now, in an attempt to make such subjects accessible and popular, media personalities such as newsreaders or comedians were used rather than those with deep knowledge who, it is often assumed, would have a daunting television presence.

Clifton-Taylor – aged and informed – seems to prove this assumption wrong. Or perhaps he was simply an oddball one-off who broke the rules, somewhat in the style of ex-steeplejack Fred Dibnah who, before his death in 2004, became something of a national institution offering home-spun opinions on most aspects of British life and particularly on things relating to steam power and 19th century engineering.

Clifton-Taylor and Dibnah were, in many ways, at opposite ends of whatever scale one might choose to use, but they had one thing in common. They both possessed that strange magic that gave them presence on the small screen.

This film starts in fine Clifton-Taylor manner. The camera pans towards the splendid medieval church tower of St John's, Cirencester and, rather than the usual predictable praise, Clifton-Taylor observes that this tower – generally the pride of this fine Gloucestershire town – is "not a success".

He says this with such profound and informed conviction (and with a touch of mischievous relish) that it seems an indisputable fact. He explains why; but I must say his reasons for this early 15th century tower's disgrace as a design tend, in my view, to be the reasons for its charm.

He explains that the tower was intended to be topped by a spire, but this was not constructed because the tower started to settle at an awkward angle soon after construction started. This led not only to the failure to construct the spire, but to the construction of a vast and most utilitarian external stone buttress at the junction of nave and tower.

Clifton-Taylor seems to hold this buttress in contempt as a badge of failure. But surely it is a wondrous thing - a pragmatic solution to a desperate problem that now tells a startling story and gives the building immense character – a bit like the visually dramatic scissor arches constructed in Wells Cathedral in the mid 14th century when the piers started to buckle. These huge, strange and almost abstract and functional forms are now one of the best things about the cathedral.

Clifton-Taylor seems to hold this buttress in contempt as a badge of failure. But surely it is a wondrous thing

Clifton-Taylor also condemns the upper stage added to the tower instead of the spire. He argues it is an artistic failure. It is certainly rather stunted and perhaps by the high standards of Medieval design he is right. But sad to say I rather like it. Need I be ashamed of my uncouth tastes?

But Clifton-Taylor seems to have liked the three-storeyed south porch – built in the 1490s as a block of offices for Black canons from a nearby abbey. He calls it "sumptuous" and "one of the sights of England".

The structurally elegant interior of the church, with its slender piers and large windows, Clifton-Taylor calls a "vast glass house", which demonstrates "Gothic structural ideas carried to their logical conclusion".

This all sounds most promising, but then he returns to his debunking routine and suggests that although "splendid" the interior is not "lovable". Oh dear. Well, the formula worked well at the time, and the format – the programme was about a town not an individual building – meant that not all the buildings featured had to be good or loved by the presenter.

In the programme most of Clifton-Taylor's opinions are delivered in sonorous voice overs, suggesting a physical fragility making his presence on location difficult. But then, within the church, he makes an appearance and, with an impish twinkle in his eye, cracks a few charmingly convoluted jokes. So, lovable as well as splendid.

More Alec Clifton-Taylor

![]()

Desert Island Discs

Listen to architectural historian Alec Clifton-Taylor pick Brahms, a set of the Shell County Guides and a bed for his castaway experience.

Art and Artists: Highlights

![]()

Ai Weiwei at the RA

The refugee artist with worldwide status comes to London's Royal Academy

![]()

BBC Four Goes Pop!

A week-long celebration of Pop Art across BBC Four, radio and online

![]()

Bernat Klein and Kwang Young Chun

Edinburgh’s Dovecot Gallery is hosting two major exhibitions as part of the 2015 Edinburgh Art Festival

![]()

Shooting stars: Lost photographs of Audrey Hepburn

An astounding photographic collection by 'Speedy George' Douglas

![]()

Meccano for grown-ups: Anthony Caro in Yorkshire

A sculptural mystery tour which takes in several of Britain’s finest galleries

![]()

The mysterious world of MC Escher

Just who was the man behind some of the most memorable artworks of the last century?

![]()

Crisis, conflict... and coffee

The extraordinary work of award-winning American photojournalist Steve McCurry

![]()

Barbara Hepworth: A landscape of her own

A major Tate retrospective of the British sculptor, and the dedicated museums in Yorkshire and Cornwall

Art and Artists

![]()

Homepage

The latest art and artist features, news stories, events and more from BBC Arts

![]()

A-Z of features

From Ackroyd and Blake to Warhol and Watt. Explore our Art and Artists features.

![]()

Video collection

From old Masters to modern art. Find clips of the important artists and their work