Devil in the detail: The visions of Hieronymus Bosch at 500

16 February 2016

Hieronymus Bosch, the Dutch genius who took his name from the market town of Den Bosch, painted nightmarish fantasies populated by supernatural beings, and all-encompassing meditations on the cycle of life. To mark 500 years since his death, the Noordbrabants Museum in the artist's home town has pulled off a major coup in staging an exhibition featuring most of the major Bosch works and accompanying drawings from around the world. WILLIAM COOK visits Visions of Genius.

Here in the Netherlands, in the cobbled backstreets of Den Bosch, the Noordbrabants Museum has mounted a stunning show in honour of this city’s famous namesake. Hieronymus Bosch - Visions of Genius is a spectacular celebration of medieval Europe’s most extraordinary artist. It’s a once-in-a-lifetime chance to see most of his hypnotic paintings in one place.

During his long career, Bosch painted countless pictures, but only 24 have survived. Remarkably, 17 of them have been brought here, along with 19 of his 20 surviving drawings, to mark the 500th anniversary of his death.

Bosch’s speciality was lurid displays of medieval depravity, but his pictures didn’t endorse immorality - they were cautionary tales

There are loans from the world’s greatest galleries: the Met in New York; the Louvre in Paris; the Prado in Madrid… Even at the Prado or the Louvre, this would be an astonishing achievement. In a small provincial city like Den Bosch, it’s an incredible coup.

How did this modest museum mount such a lavish retrospective? The answer is an object lesson in how to stage a major exhibition.

The Noordbrabants Museum didn’t just ask for loans - they offered restoration and research. Nine paintings have been beautifully restored. Local archivists have shed fresh light on the world in which Bosch lived and worked.

Hieronymus van Aken was born in Den Bosch around 1450, and adopted the name of his hometown to promote his work. His father and grandfather were both painters. Bosch followed in their footsteps. He spent his whole life in Den Bosch and worked as a painter here throughout.

Bosch was born in a simple house on the city’s market square. He ended up in a much smarter house, just across the street. Bosch would still recognise this bustling marketplace. Flanked by rows of gabled houses, it still looks much the same today. A new set of sculptures have been installed here, depicting the strange creatures in his artworks. Here in Bosch’s historic hometown, life is imitating art.

Bosch’s speciality was lurid displays of medieval depravity, but his pictures didn’t endorse immorality - they were cautionary tales.

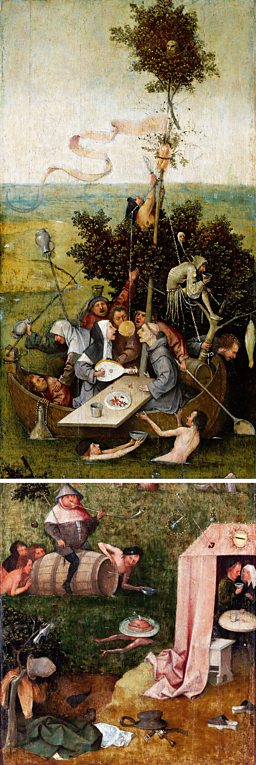

The titles of these paintings tell their own stories: Death and the Miser; Gluttony and Lust. The Ship of Fools portrays a boatload of randy, drunken revellers; The Last Judgment shows what punishments these sinners will suffer in the afterlife (in one corner of the picture - right of centre in the detail above- a naked man lies prostrate across an anvil, while a ghostly figure hammers something hard and horrid up his bum).

Visions of Genius brings together some dismembered works; The Ship of Fools (Louvre, Paris) and Allegory of Gluttony and Lust (Yale University Art Gallery), which were probably sawn in two in the early 19th century, are displayed together for the first time.

Above: Gluttony and Lust (fragment of Ship of Fools) c. 1500–10 | Photo Rik Klein Gotink and image processing Robert G. Erdmann / Top: The Ship of Fools, c. 1500–10 | Photo Franck Raux

Waldemar on Bosch

![]()

500 years of Bosch

Listen to Waldemar Januszczak explain the importance of the Visions of Genius exhibition and the work of Hieronymus Bosch.

Bosch’s pictures were meant as warnings, to tell people to stick to the straight and narrow, but he painted them with such relish, you can’t help thinking he must have got a secret kick out of portraying torture and vice.

Never before in art history was there a painter who was so creative - he's very original, very modernCharles de Mooij, director, Noordbrabants Museum

In The Ship of Fools a flirty nun canoodles with a greedy monk. In The Last Judgement a naked man slides down the blade of an enormous knife (ouch).

How did Bosch get away with it? Why did the Catholic Church allow him to paint such explicit scenes? Actually, these paintings aren’t quite as subversive as they seem. Bosch mocked the laity and lower clergy, but he never criticised the Church itself.

Like a tabloid editor printing sexual exposes alongside pious editorials, he knew how to have his cake and eat it. Yet as an artist, he was revolutionary. No wonder he was called ‘the devil’s painter.’

‘Never before in art history was there a painter who was so creative,’ says Charles de Mooij, director of the Noordbrabants Museum. ‘He’s very original, very modern. You always discover new things with Bosch.’

The artists he inspired the most aren’t the Old Masters of the 16th Century, but 20th Century Modern Masters like Salvador Dali and Max Ernst.

What was the root of his unique vision? Where did these fantastical pictures come from? His hometown was some help. An important market town, Den Bosch was prosperous enough to support a family of artists, but it didn’t have a lively arts scene. In a big city like Amsterdam or Antwerp, he would have been influenced by other artists. Here, he was free to be himself.

However Den Bosch was only part of it. There were lots of other artists toiling away throughout the Low Countries at that time, yet none of them could match his technical skill, or his boundless imagination. His style and subject matter seemed to spring from nowhere. His imitators seem flat and stilted. For once, that overused tag, ‘creative genius,’ seems justified.

Visions of Genius isn’t all sex and violence. This comprehensive survey shows that Bosch was devoutly religious. Some of his finest pictures are his sensitive paintings of the saints.

However it’s his dark, dreamlike fantasies which really capture the imagination: a clog becomes a boat; people are trapped inside a giant egg; humans mutate into hideous birds and beasts.

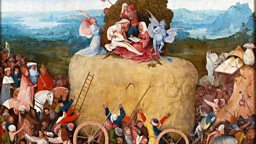

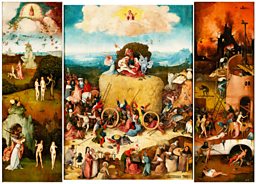

The Haywain Triptych

The crowning glory of this splendid show is The Haywain, from the Prado – the first time it’s left Spain in nearly 500 years. People fight over this golden hay, unaware that it’s really worthless. This triptych takes the form of a procession, from heaven through the fallen world and into hell.

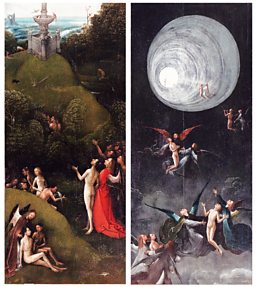

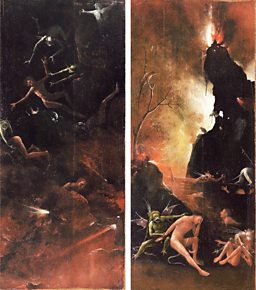

Visions of Genius concludes with The Way to Heaven and The Way to Hell – two remarkable diptychs portraying the two afterlives that preoccupied the medieval mindset. Both paintings are amazing.

Experts think these abstract patterns are meant to resemble marble, but to me they look more like Jackson Pollock

The Way to Heaven depicts a tunnel of light, with angels carrying good Christians up to paradise. The Way to Hell depicts gleeful devils dragging sinners into the abyss. They’re unlike anything in medieval art. This is the dawn of the Renaissance.

The back panels of these diptychs are splattered with random splashes of bright paint. Half a millennium since he made them, these daubs still look fresh and vital. Experts think these abstract patterns are meant to resemble marble, but to me they look more like Jackson Pollock.

This is a man who’s broken free from the confines of his art. On one of his playful drawings, Bosch has scrawled a Latin motto: ‘Pitiful is he who always makes use of the inventions of others and never creates anything himself.’

Hieronymus Bosch - Visions of Genius is at the Noordbrabants Museum, Den Bosch, The Netherlands, until 8 May 2016.

Visions of the Hereafter

Free Thinking on Radio 3

![]()

Hieronymus Bosch

Tom Shakespeare, film director Peter Greenaway and art historian Matthijs Ilsink join Matthew Sweet in Holland for Visions of Genius, 22:00 Tuesday 16 February.

More from BBC Arts

![]()

Picasso’s ex-factor

Who are the six women who shaped his life and work?

![]()

Quiz: Picasso or pixel?

Can you separate the AI fakes from genuine paintings by Pablo Picasso?

![]()

Frida: Fiery, fierce and passionate

The extraordinary life of Mexican artist Frida Kahlo, in her own words

![]()

Proms 2023: The best bits

From Yuja Wang to Northern Soul, handpicked stand-out moments from this year's Proms