The painters' painter: A rare meeting with Frank Auerbach

9 October 2015

As a major retrospective for revered - and reclusive - painter Frank Auerbach opens at Tate Britain, STEPHEN SMITH has secured a rare interview to be broadcast on BBC Two's Newsnight and BBC Radio 4's PM. Here he writes for BBC Arts on his meeting with one of the world's greatest artists.

Jeremy Corbyn isn’t the only gent of pensionable age who’s finally getting some attention after years of ploughing a lonely furrow.

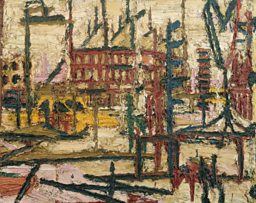

This is also a moment in the sun for Frank Auerbach, who’s been called the country’s greatest living artist after carving out his own idiosyncratic line of beauty, the result of his extraordinary sapper work with paintbrush and palette knife.

What I’m trying for is something that works and is true to the subject

He’s also known as the painters’ painter, which is a kind way of saying that he’s not necessarily on the radar of everyone who crosses the threshold of a gallery. But now Frank, as everyone seems to call him, is en fête, with a retrospective occupying a good many rooms at Tate Britain.

It’s a glorious outcome that few could have predicted for the boy of seven who arrived here from Berlin on the kindertransport, spared the concentration camps which consumed his parents.

At 84, he’s outlived his friends and fellow artists, the roaring boys Francis Bacon and Lucian Freud. The Quiet Musketeer has even emerged from their shadow, with a good Auerbach setting you back north of £2million these days.

And today Frank walks into the Tate’s elegant grand saloon with the look of a man 20 years younger – Jeremy Corbyn, say – and sits down in front of our camera without demur.

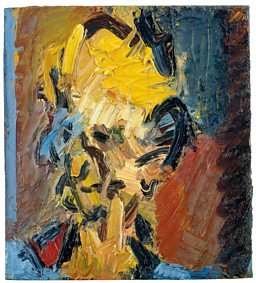

This in itself is astonishing, as astonishing as encountering his art in the flesh – or rather, in all its molten-tallow avoirdupois (WH Auden famously thought his face looked like a wedding cake left out in the rain. Goodness knows what Mary Berry would make of some of Auerbach’s faces, with their complexions of raw egg yolk and quivering jowls of icing sugar.)

The thing is, Frank doesn’t do interviews, not for broadcast, at any rate. This inveterate portrait painter last sat for the lens at the turn of the century, and that was when his own son Jake was behind the camera. Many requests for a follow-up appearance have been politely declined on Frank’s behalf.

Meanwhile reports reaching the outside world from his studio in North London have encouraged the romantic notion of a reclusive artist. He lives over the shop, they say, sleeping on a rude cot.

Like the mature Cezanne, who returned endlessly to Monte St Victoire in Provence, Frank has found everything he needs to nourish his eye on the Grand Union Canal Riviera - Camden, Primrose Hill and Mornington Crescent – a short distance from home.

You have to invent, to struggle, until you end up with something that can go out in the world and stand up for itself

His long-suffering wife and sitter, Julia, buys his corduroy suits from an outfitter who supplies agricultural shows. Every decade or so, she orders a new one.

But the man sitting before me, smiling genially and discussing his fondness for comedians (Tommy Cooper and George Formby), is every inch the distinguished man of the arts. Even the chocolate suit is less John Craven than, shall we say, John Gielgud, and is set off today by a fetching brown scarf with Seuratish spots and dots.

The problem isn’t getting Frank talking – perhaps in reaction to all those hours of solitary work, he is a thoughtful and lively conversationalist – but if it’s all the same to everyone else, he’d always rather be painting.

"What I’m trying for is something that works and is true to the subject," he says. "You’re working with the (two-dimensional) canvas but also trying to create a design that works in space. At times it seems almost impossible. To do it you have to invent, to struggle, until you end up with something that can go out in the world and stand up for itself."

This struggle explains the impasto which looks like it’s risen too high in the oven. The late, great Robert Hughes, who thought enough of Frank to devote a long monograph to him, records the apocryphal story of the nightwatchmen at a Melbourne Gallery who used to turn their Auerbach upside down after hours, so that the paint wouldn’t slide off the bottom of the frame.

Frank says: "When I started painting it was very, very thick, but it was never a case of sloshing it on. I was trying to do something new and I didn’t have the courage to scrape it all off."

It seemed pathetic having an interesting and exciting life and leaving no trace of it

Freud admired Frank’s project so much that he acquired a substantial collection. "He bought them from a dealer and owned many of my better pieces. In fact, I became a bit worried that they were all in the same place - it might have burned down."

Freud managed to avoid setting fire to his Auerbachs but he certainly burnt the candle at both ends. It was thanks to him that Frank gazed upon the chemin-de-fer tables at the Playboy Club.

"Lucian, who gave the impression that he didn’t know the price of a pack of cigarettes, suddenly became this maths genius. He was playing three games of chemmy at once and he won £1,600 – an enormous sum of money in those days.

"I became concerned that he would lose it so I persuaded him to drive me home. I saw him again a couple of days later and he told me he went straight back to the tables and lost the lot. At one time he owed money to the Krays."

Frank says his own life was "adventurous enough for him" but nothing came before art. Was there a sense that he wanted to give a good account of a life which he’d almost not been allowed to live?

"Finally, between the cradle and the grave, one is alone. You’re making me say things that I’ve never thought of but yes, life is short and dangerous, or so it seemed to anyone who lived through the war. And it seemed pathetic having an interesting and exciting life and leaving no trace of it. And the only trace I could think of was art."

Frank Auerbach is at Tate Britain until 13 March 2016.

Related Links

Art and Artists: Highlights

![]()

Ai Weiwei at the RA

The refugee artist with worldwide status comes to London's Royal Academy

![]()

BBC Four Goes Pop!

A week-long celebration of Pop Art across BBC Four, radio and online

![]()

Bernat Klein and Kwang Young Chun

Edinburgh’s Dovecot Gallery is hosting two major exhibitions as part of the 2015 Edinburgh Art Festival

![]()

Shooting stars: Lost photographs of Audrey Hepburn

An astounding photographic collection by 'Speedy George' Douglas

![]()

Meccano for grown-ups: Anthony Caro in Yorkshire

A sculptural mystery tour which takes in several of Britain’s finest galleries

![]()

The mysterious world of MC Escher

Just who was the man behind some of the most memorable artworks of the last century?

![]()

Crisis, conflict... and coffee

The extraordinary work of award-winning American photojournalist Steve McCurry

![]()

Barbara Hepworth: A landscape of her own

A major Tate retrospective of the British sculptor, and the dedicated museums in Yorkshire and Cornwall

More from BBC Arts

![]()

Picasso’s ex-factor

Who are the six women who shaped his life and work?

![]()

Quiz: Picasso or pixel?

Can you separate the AI fakes from genuine paintings by Pablo Picasso?

![]()

Frida: Fiery, fierce and passionate

The extraordinary life of Mexican artist Frida Kahlo, in her own words

![]()

Proms 2023: The best bits

From Yuja Wang to Northern Soul, handpicked stand-out moments from this year's Proms