The pop-up hit factory: How a songwriter bootcamp helped Rihanna fight back

7 October 2015

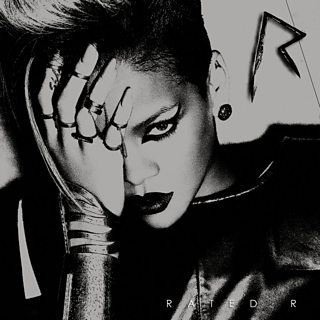

Pop sensation Rihanna has opened up to Vanity Fair magazine about the assault she suffered at the hands of her ex-boyfriend Chris Brown in a frank interview ahead of the release of her eighth album. In his new book about the music industry, The Song Machine, New Yorker writer JOHN SEABROOK describes how the aftermath of the 2009 incident led to the creation of her acclaimed fourth album, Rated R - a radical sonic departure which erased any impression of the Barbadian singer as a victim. In this exclusive extract, Seabrook describes the incredible songwriting camp from which the album was born, lifting the lid on the hidden processes behind the world's biggest pop records.

As with many of Rihanna’s albums, Rated R, her fourth, began with a writer camp. There was a real danger that the artist’s career could be seriously damaged by the beating [at the hands of Chris Brown], especially among her younger fans, many of whom seemed to be willing to forgive Brown because, as it was said by astoundingly vicious YouTube haters, “the bitch hit him first.”

A lot of people had invested a huge amount of time, energy, and money in building up the Rihanna brand, and with Umbrella it was poised to become very, very profitable. But in a moment her image had changed. She wasn’t the haughty ice princess of the fashion mags. She was a victim. She bleeds.

A-list producers and topliners were summoned to Los Angeles for two weeks and installed in studios around the city, their hotel and food all paid for

L.A. Reid, who was still running Def Jam in the wake of Jay-Z’s departure, was determined not to lose all they had invested in the young star. He put on the mother of all song camps.

A-list producers and topliners were summoned to Los Angeles for two weeks and installed in studios around the city, their hotel and food all paid for. It was the kind of immensely expensive undertaking that only a major label can afford to arrange.

Nowhere are the production efficiencies of the track-and-hook method of writing better realised than in writer camp. A camp is like a pop-up hit factory. Labels and superstar artists convene them, and they generally last three or four days.

The usual format is to invite dozens or more track makers and topliners, who are mixed and matched in different combinations through the course of the camp, until every possible combination has been tried. Typically, a producer-topliner pair spends the morning working on a song, which they are supposed to finish by the lunch break. In the afternoon new pairs are formed by the camp counselors, and another song is written by dinner.

If the artist happens to be present, the artist circulates among the different sessions, throwing out concepts, checking on the works in progress, picking up musical pollen in one session and shedding it on others.

At the end of each morning and afternoon session, the campers come together and listen to one another’s songs. The peer pressure is such that virtually every session produces a song, which means twelve or more songs a day, or sixty a week, depending on the size of the camp.

The Rihanna writer camp was an elite affair. Ne-Yo was there, as was [Scandinavian production duo] Stargate, and Ester Dean. Jay Brown played counselor to the campers, under the aegis of Def Jam management.

For Ester Dean, writing for Rihanna was liberating... she became the woman she imagined Rihanna was

For Dean, writing for Rihanna was liberating. In spite of her earthy vocabulary and her ’hood style, Dean was a prude at heart, and her inner Baptist minister regretted her transgressions.

But writing for Rihanna set her bad girl free. She became the woman she imagined Rihanna was, a woman Rihanna herself, tall and slim and sexy, would never aspire to be with such urgency: a swaggering vixen.

In Dean’s demos for her Rihanna hits, which can be heard on YouTube, it’s hard to tell whether she is channeling Rihanna or Rihanna is copying Dean. “People put comments on my YouTube demos saying stuff like, ‘This cover sucks,’ ” she says indignantly. “I ain’t never covered a song in my life!”

Rude Boy was the work of five different songwriters, including Makeba Riddick, who helped [Rihanna] write the bridge, and Rob Swire, who contributed to Stargate’s production work. (Hermansen wrote and played the chord progression on this song too.) The hooks were pure Ester Dean.

The first hook comes right away in the song, a sort of rhythmic pre-chorus, followed by the main hook, which will become the refrain of the song. Then a third hook, “take it, take it”—is the full Esta.

And then there’s a fourth hook—“what I want want want”—another straight-from-the-mouth classic—which brings us back to the title hook again. The track-and-hook method of songwriting reaches its apotheosis with Rude Boy; the song is virtually all hooks.

Rated R erased any lingering impression of Rihanna as a victim

Rude Boy is a concise illustration of Stargate’s gift to urban music. The beats are crisp and hard, but the crystalline synth chords lift the song from its crude lyrical context—challenging a rude boy about his manhood—and makes it sound like a love song.

Musically, a Scandinavian snowfall filters down over a sweaty Caribbean drum circle. The stuttering sound that the chords make, created with a software module known as an arpeggiator, would become perhaps the signature Stargate sound.

Stargate had achieved with Rude Boy what the Swedes, for all their melodic gifts, were never able to pull off: a perfect hybrid of Nordic and urban. It marked the start of a hot streak that would bring the duo such smashes as Firework, Only Girl (In the World) and S&M— all collaborations with Ester Dean.

In 2010, ASCAP named them songwriters of the year. In 2011 Rihanna’s Only Girl (In the World) won them their first Grammy, for Best Dance Recording.

Most important of all, at least from L.A. Reid’s perspective, Rude Boy in particular, and Rated R in general, erased any lingering impression of Rihanna as a victim. The gentle island girl-next-door Evan Rogers signed in Barbados is gone, and a steel-plated Valkyrie is firmly, and coldly, in control.

From the Ellen von Unwerth cover photo of the unsmiling artist in mesh and black leather, palm cupped over one of her previously blackened eyes as though it still ached, to the lyrics of the lead single, Russian Roulette, and the second single, Hard, and the song Cold Case, the whole album obliquely refers to the beating; Stupid in Love explicitly so, with its line about blood on your hands.

Timbaland was on the album, as well as Will.i.am, Justin Timberlake, and many other top producers and songwriters—even Slash, the former Guns N’ Roses guitarist, makes an appearance. A notable exception was [her original production duo] Sturken and Rogers. Rated R is the first Rihanna album without a single cut from them on it.

The Song Machine, by John Seabrook, is published by Vintage on 8 October.

Related Links

More from BBC Arts

![]()

Picasso’s ex-factor

Who are the six women who shaped his life and work?

![]()

Quiz: Picasso or pixel?

Can you separate the AI fakes from genuine paintings by Pablo Picasso?

![]()

Frida: Fiery, fierce and passionate

The extraordinary life of Mexican artist Frida Kahlo, in her own words

![]()

Proms 2023: The best bits

From Yuja Wang to Northern Soul, handpicked stand-out moments from this year's Proms