The Evolution of our Favourite Christmas Carols

🎵 Fa-la-la-la-la, la-la-la-la!

We hear them every year, echoing through shops, churches and town squares, but how often do we pause to consider the origins of our favourite Christmas carols?

Here is a brief look at six carols that have shaped the sound of the festive season.

There is no rose

There is no rose of such virtue

Alleluya

As is the rose that bare Jesu.

Alleluya.

This hauntingly beautiful carol is one of the most cherished from the medieval period. It comes from the Trinity Carol Roll, a 15th-century manuscript containing a collection of 13 anonymous English carols, which is kept at Trinity College, Cambridge.

The original softly lilting carol is what’s called a ‘macaronic’ carol, where Latin words or phrases are interspersed throughout the English text.

It’s particularly beautiful for its use of the ‘rose’ as a metaphor for the Virgin Mary. In its original medieval choral setting, it conjures a brilliant sense of wonder with its modal harmonies and gently meandering melody.

Over the centuries ‘There is no rose’ has inspired many to set the text to music of their own. One of the most famous examples is by Benjamin Britten, who included a setting in his celebrated Ceremony of Carols.

Contemporary English composer Cheryl Frances-Hoad composed her own setting of ‘There is no rose’ in 1995, when she was only 14 years old. It’s a stunning alternative to the original, bursting with expansive harmonies, expressive word painting and miraculous dynamic contrasts.

Tomorrow shall be my dancing day

Tomorrow shall be my dancing day;

I would my true love did so chance

To see the legend of my play,

To call my true love to my dance.

Sing, O my love,

O, my love, my love, my love,

This have I done for my true love.

‘Tomorrow shall be my dancing day’ first appeared in print in William Sandys’s Christmas Carols Ancient and Modern (1833), but the piece is widely believed to be much, much older. Before its publication, it circulated on ballad broadside sheets in Britain, so it's likely that the song was sung in communities long before it was written down.

This cheerful carol is a curious piece in many ways, not least because it’s one of the few carols told from a first-person perspective. It’s also unusual in the way it recounts the whole life of Jesus Christ, from his birth to his crucifixion, so it can be sung throughout the whole Christian year.

Still, many of the lyrics don’t make much sense. What exactly is meant by the ‘dance’ or ‘play’? Are they a nod to Christ’s second coming, or echoes of medieval mystery plays? The truth is, we don't know.

The carol didn’t become widely popular until the 20th century, when Richard Runciman Terry arranged it in the 1930s. A more expansive and enduring version by David Willcocks followed in the 1960s, and it’s this arrangement that is most commonly sung today.

Of course, many composers have made their own arrangements or composed entirely new settings of the carol, including Gustav Holst, John Gardner and Igor Stravinsky. Carl Rütti’s ‘My dancing day’ is a recent, joyous setting for choir and organ. It bursts with tremendous spirit and jazz-inspired harmonies, while a pulsating bass keeps the momentum fizzing along throughout.

Away in a manger

Away in a manger, no crib for a bed,

the little Lord Jesus laid down His sweet head

the stars in the bright sky looked down where He lay,

the little Lord Jesus asleep on the hay.

One of the most popular carols in Britain, ‘Away in a manger’ is also among the youngest, dating back only around 140 years. Despite this, compared to many other traditional carols its history is surprisingly muddled.

For such a beloved carol, its authorship and early development remain unclear. When the carol first emerged in print in the 1880s, it was attributed to Martin Luther – and while Luther did write many hymns, this wasn’t one of his.

Instead, it’s widely thought that ‘Away in a manger’ is an entirely American creation, likely originating among German Lutherans in Pennsylvania around 1885. A third verse was added in 1892, which, like the first two verses, was mistakenly attributed to Luther. Despite various claims over the years, the true authorship of the carol remains unknown.

Regardless of the muddle, ‘Away in a manger’ has inspired more musical settings than almost any other carol. In Britain, the most familiar is William J. Kirkpatrick’s ‘Cradle Song’, whereas in the USA the ‘Mueller’ melody is more commonly sung. Another notable arrangement comes from Reginald Jacques, who in 1911 paired the lyrics with the melody known as the ‘Old Normandy Carol’.

More recent reworking include Ashley Grote’s reharmonisation and Lucy Walker’s 2023 interpretation, which offers a darker, more contemplative take on the carol. Set in the minor key, it retains the gentle sway of a lullaby and a folk-like refrain, while each verse introduces a new musical texture that mirrors the shifting focus of the text.

In dulci jubilo

In dulci jubilo

Let us our homage shew:

Our heart’s joy reclineth

In praesepio;

And like a bright star shineth

Matris in gremio,

Alpha es et O!

‘In dulci jubilo’ is one of the jolliest carols sung at Christmas time – a lively, lilting dance whose title means ‘in sweet rejoicing’ in Latin.

The carol’s origin story is just as charming as its uplifting melody. According to legend, a 14th-century German monk named Heinrich Seuse was visited by an angel sent from God to comfort him during a time of suffering. In Leben Seuses, his possible autobiography, the narrator recounts how the angel joined him in a dance and sang a joyful ditty about the infant Jesus, beginning with the words ‘In dulci jubilo’.

While there’s no link between this story and the carol’s earliest known melody, by the mid-1500s the tune had become a well-loved favourite. It appeared in carol collections, including a 1545 publication featuring a new verse, possibly written by Martin Luther.

J. S. Bach drew on ‘In dulci jubilo’ many times throughout his career, most notably for an organ prelude, which remains a favourite in Christmas services today. In more recent years, composer Cecilia McDowall’s new setting of the text is a charming alternative to the medieval carol, capturing the same lilting, joyous spirit. As part of her Christmas cantata A Winter’s Night, she also made a merry arrangement of the original melody for choir, organ and orchestra.

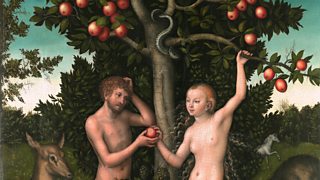

Adam lay ybounden

Adam lay ybounden

Bounden in a bond;

Four thousand winter

Thought he not too long.

The most famous setting of this 15th-century text is Boris Ord’s from 1957, introduced to the Nine Lessons and Carols service at King’s College, Cambridge where Ord was organist.

The text’s original author is unknown and focuses on the Fall of Man as described in the Book of Genesis. In the third verse, man is redeemed by the birth of Jesus Christ, who will later sacrifice himself for our sins, and Mary, his mother, will become the Queen of Heaven.

There are many popular settings of ‘Adam lay ybounden’, including by the 20th-century carrolist Peter Warlock. A very fine recent carol comes from Irish composer Laura Sheils, whose lively setting is full of shifting time signatures, syncopated rhythms and independently moving vocal lines.

Coventry Carol

Lully, lullah, thou little tiny child,

Bye bye, lully, lullay.

The Coventry Carol is one of the most haunting Christmas carols, sung from the perspective of anguished mothers attempting to soothe their babies – children fated to die at the behest of King Herod.

While the carol was first written down in 1534, its origins are much, much older. It was originally part of a medieval mystery play, The Pageant of the Shearmen and Tailors, performed in the city of Coventry each year from the late 12th century. The lullaby-lament reflects on the Massacre of the Innocents from the Nativity story, its mournful melody set in the minor key.

It was boosted in popularity following the BBC’s Empire Broadcast at Christmas 1940, shortly after the devastating bombing of Coventry in the Second World War. The broadcast concluded with the carol sung in the bombed-out ruins of the Cathedral.

Today, the carol is enduringly popular and has a special place in the Christmas musical canon. It has inspired many modern interpretations of the text, including Philip Stopford's beloved setting ‘Lully, Lulla, Lullay’ and an emotive take by Emily Hazrati.

The BBC Singers will be performing carols throughout the festive period, including Emily Hazrati’s ‘Coventry Carol’, Carl Rütti’s ‘My Dancing Day’, Ashley Grote’s arrangement of ‘Away in a manger’. Why not join us in person for a concert to warm your spirits?

Come and join us on Thursday 11 December at Milton Court Concert Hall for A Christmas Odyssey with Adrian Scarborough, and for Carols from Temple Church on Friday 19 December 2025, broadcast live on Radio 3.

![]()

BBC Singers Features

Articles, quizzes and more from the BBC Singers

![]()

Watch & Listen

Experience the BBC Singers in bite-size chunks.

![]()

About the Singers

Meet members of the BBC Singers and their conductors.

![]()

BBC Radio 3

Arts, culture, music and ideas from the BBC – and the home of the BBC Proms on air. Listen live on BBC Sounds.