Five Fantastic Fugues for organ, not by Bach

Most of the music we hear around us takes the form of tune and accompaniment. One voice leads with a melody, all the other parts sit, more-or-less, in supporting roles. Fugue is different. In a fugue, every part is treated equally and takes a turn playing the lead. As each voice picks up the main melody or ‘theme’, the others don’t simply recede into the background, they continue alongside with complementary countermelodies that weave around the theme, and all the other countermelodies, in a complex tapestry of musical lines.

There are rules to writing fugues – conventions of harmony, melody and structure that composers can follow, flirt with or break entirely. Voices usually enter one after another (the latin ‘fugare’ means ‘to chase’) and there is a catalogue of clever part-writing techniques that composers are free to plunder, if they’re skilled enough to master them. A key thing to notice about fugues is that the main theme rarely dances prettily in the spotlight, as it does in other kinds of music. It moves like an individual through a crowded street, or like a wild idea through a heated conversation. Sometimes the flow is smooth and balletic, sometimes it is jostled and bumped about. Fugues can be complex to follow. They are even more complex to play, especially if you only have two hands and two feet at your disposal. Even so, the organ, with its sustaining power, and equally matched voices has proved a perfect vehicle for realising fugues. Organists, who can’t resist a bit of musical grandstanding, can’t seem to get enough of them.

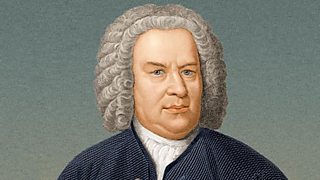

J.S Bach was the master. His best fugues seem to show us not just the soul of the composer, but a glimpse into the very wheels of creation too. Three of my favourites are the five-part Fugue in Eb that ends his “Clavierubung III”(commonly but erroneously known in Britain as “St. Anne” and routinely paired with Prelude in Eb that begins that volume), the joyful final movement from his Toccata Adagio and Fugue in C major and the titanic confidence of his Fantasia and Fugue in Gm. But many other composers have produced great organ fugues. Here are our top five.

Mozart: Fantasia in F minor, K. 608

Both Mozart and Beethoven knew and admired Bach’s music, especially his ‘48’ preludes and fugues for Well-Tempered Keyboard. Both were inspired by Bach’s example to create some of the great fugues of classical era: in their piano music, vocal works and string quartets. Alas, neither of them left behind more than a handful of minor works for organ. Why is that? As town councils competed with each other, organs were growing in size and complexity, but perhaps not sophistication. It’s possible that these monumental and imposing instruments just didn’t appeal to composers who were so concerned with the subtleties of human expression. It’s telling that Mozart’s Fantasia was composed not for a human player, but for an organ that formed part of a mechanical clock. Nonetheless, this short work is a little organ gem. It doesn’t feature a separate fugue movement. Rather, moments of fugal writing pop up in the opening section, and before the end. As they begin, we might even mistake these sections for Bach’s own writing; a knowing nod, perhaps, from one musical genius to another, before Mozart takes over and makes the music all his own.

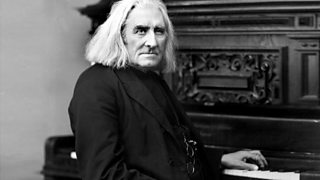

Liszt: Prelude and Fugue on BACH

Liszt wasn’t the first composer to use the letters in Bach’s name to spell out a musical theme. That was Bach himself. In German notation, they conveniently spell out the notes B flat, A, C and B natural. Musicians will notice that these notes all lie right next to each other on the keyboard – just a semitone apart. As such, they don’t immediately suggest a particular key. That’s important because, traditionally, a fugue sets out in a clear ‘home’ key at its start, moves to more distant keys in the middle, and then brings us back home again at the end. You don’t need to understand music theory harmony to appreciate this, by the way. Music written in this manner instinctively ‘feels’ like it’s taken us on a journey and come back again. Liszt jumps on his ‘B.A.C.H’ motive as a way to deliberately avoid a sense of home key. Instead, he whisks us through a dizzying whirlwind of chords and harmonies that surprise and disorientate with their constant twists and turns. It’s thrilling and unsettling all at once. He doesn’t leave us to flail about completely lost, though. The insistent, ear-caching ‘BACH’ motive gives us something to cling onto, a familiar landmark among the torrent of notes. And there’s something else to help us here. Without keys as our guide, Liszt draws us though the music with a parade of different rhetorical styles. He’s like an actor delivering a great dramatic soliloquy. Sometime he’s whispering to us seductively, sometimes he’s hectoring, sometimes he’s lamenting and sometimes he’s proudly proclaiming. In doing so, Liszt demands a newly expressive voice from both instrument and player. Liszt showed organs could emote, just like his his beloved piano. Organ fugues would never be the same again.

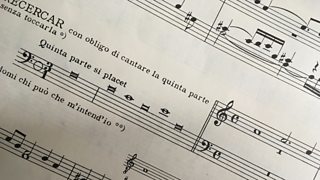

Girolamo Frescobaldi: Recercar con obligo di cantare la quinta parte senza toccarla

Frescobaldi lived almost exactly a century before Bach. He was organist at St. Peter’s in Rome and became one of the most respected and influential composers of keyboard music in the western world. Bach made his own handwritten copy of Frescobaldi’s collection, Fiori musicali (‘Musical Flowers’) from which this Recercar (an early variety of Fugue) is taken. Even more importantly, for Frescobaldi’s reputation, music from this collection was mined by Joseph Fux for his treatise Gradus ad Parnassum – the textbook on traditional music theory, which diligent musicians have studied since 1725, and still do today.

This ‘recercar’, which was originally designed to be performed during the offertory of a service in honour of Mary, is set out as a conventional four part fugue for organ. But Frescobaldi also writes, at the top of his manuscript, a mysterious sequence of six notes. It’s a ‘fifth part’ he explains, which is to be sung alongside the four keyboard parts. The melody fits perfectly over the top of the other four voices in several places. But it’s up to the performer to find where those places are! Underneath, Frescobaldi cryptically writes: ‘Intendami chi puo che m'intend' io’ (He who can understand me, will understand me; I understand myself.)

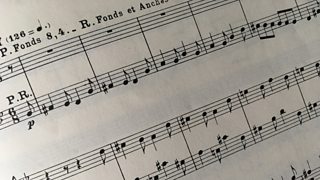

Dupré: Prelude and Fugue in G minor

As the 19th century gave way to the 20th century, Bach’s popularity and influence only grew stronger and more pervasive. The rather forgotten composer of a few old-fashioned keyboard pieces that Mozart knew was now being hailed as the founding father of the entire Western classical tradition. Organists, in particular, kept a special place in their heart for this musical demigod who was ‘one of us’. Bach remained a jobbing organist, who never lost his passion for this extraordinary instrument. We hear that admiration in the many, many preludes and fugues that organ composers have produced in the shadow of Bach’s exemplars.

Evolving organ technology, and successive generations of performers who’ve taken virtuosity to ever more astounding heights, have allowed fugue composers, particularly, to relentlessly outdo themselves in complexity and difficulty - not always with appealing results. This G minor fugue from Marcel Dupré is a fine example of music that has all of the technical panache that Bach would expect – but also Bach’s sense of ebullience and majesty, and a musical line that catches the ear and just won’t let go.

It’s also fiendishly difficult to play, as is made clear in the words organists have devised to fit the opening melody. Not all the versions of this lyric, which I imagine has been passed from organist to organist for the last century or so, are printable – but a slightly sanitised version I came across goes: ‘Marcel Dupré, Marcel Dupré / He wrote a fugue that's hard to play! / I hate you, I hate you Marcel Dupré / I hate you I hate you Marcel Dupré’.

Toccata in Fugue in D minor BWV.565

It’s one of Bach’s most renowned works and possibly the most famous piece of organ music in the world. And yet, quite a lot of experts believe it wasn’t composed by Bach at all. No original manuscript exists in Bach own handwriting, plus there are lots of unusual features about the music that don’t match what we know of Bach’s usual style. For starters, there’s that minor cadence at the very end. No other genuine Bach work has the same fingerprint. And the fugue isn’t as rigorously worked-out as many other examples by Bach. It’s a bit ‘loose’. In places, the composer completely abandons the clever counterpoint we usually expect in Bach’s writing in favour of obviously flashy keyboard flourishes. ‘Never mind the erudition’ is seems to say ‘look how many notes I can play - and how fast!” . Some have suggested that this flamboyance points to it being the work of a precocious teenager. If it were a piece from Bach’s youth, one that maybe he found a bit embarrassing, it might explain the lack of original documents. Although, the Bach scholar, Peter Williams pointed out that the Italian terms scattered through the music indicate a rather later date of composition.

One theory has it that this isn’t even organ music. Andrew Manze is just one of many violinists who have shown just how comfortably it lies under the fingers for that instrument. We know that Bach made his own organ transcriptions of violin concertos by Vivaldi and others. Maybe this is another?

Professor Christoph Wolff, director of the Bach Archive in Leipzig, suspects research will eventually prove beyond doubt that this is an original work by Bach. It’s unusual features, he suggests, are just another demonstration of Bach’s extraordinary creative range. Until then, organists and listeners are free to put the debate to one side and simply enjoy the brilliance of music that for many, is ultimate in organ writing.