Graffiti grievance: When street artists and big brands clash

12 September 2018

To have your artwork in an advertising campaign starring one of the world’s hottest footballing talents might sound like a dream come true. What if you weren’t asked or paid? BRUCE MUNRO finds street artists around the world are fighting for their intellectual property rights.

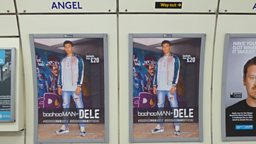

With an estimated market value of £90 million and a huge following on social media, footballer Dele Alli is an attractive commercial proposition. In May, menswear collection with high street fashion chain boohooMAN announced a collaboration with the England and Tottenham star. This attracted positive attention in the press and his Instagram announcement on 7 May attracted over 100,000 likes.

Nobody asked my permission and nobody got paid...SPZero76

But nestled within the comments is some serious criticism from the street art community. For one user it was a case of "ripping off street artists to make you look edgy, pathetic", and another complained boohooMAN was "a company which is using artists' work without permission, acknowledging them or even paying them".

With posters all over the transport system in London, the artists involved were quick to spot their work. On 9 May, Si Mitchell from the Lost Souls crew alerted both the brand and player on Instagram, stating it was an "UNOFFICIAL COLLAB... Get in contact I would like to discuss this!"

Fellow Lost Soul SPZero76 also voiced his frustration, arguing "nobody asked my permission and nobody got paid..."

Most of the images were created during paint jams – events where streets artists get together to create new works – organised by London Calling Blog, a site which celebrates street art.

If no agreement can be reached, our instructions are now to issue formal legal proceedings against BoohooJoshua Schuermann

The Lost Souls crew were not the only artists affected. According to London Calling, work from 14 different artists featured in boohooMAN photographs in posters or online. As well as voicing their frustration on social media, many of those artists are consulting with lawyers.

Joshua Schuermann, an intellectual property solicitor from Briffa, is representing 11 of the artists involved. He said: "The art was created legally, in a private space. The artists never assigned or licensed the use of the art, so they retain ownership of copyright.

"We informed Boohoo of the infringement months ago, but the images have only been removed recently. We are currently in discussions with Boohoo to resolve the dispute without needing to issue proceedings. If no agreement can be reached, our instructions are now to issue formal legal proceedings against Boohoo for the infringement of our clients’ copyright."

The company says it was misinformed about the images within the venue.

We relied upon the venue's assurance that all artistic works were licensed.Boohooman

In a statement to BBC Arts they said: "BoohooMAN has its own in-house creative teams and respects the rights of artists. BoohooMAN support grassroots talent and enjoys working with many different artists and venues. In this instance we relied upon the venue's assurance that all artistic works were licensed. We have subsequently been informed by a number of artists that the venue’s assurances were not correct and are seeking to resolve the situation with all parties concerned."

Steve Walsh, founder of the London Calling Blog, said he did not discuss the issue of intellectual property with the owners of the space – Arts charity Uthink – or the individual artists.

Major corporations are attempting to cash in on a scene that is currently extremely popularSteve Walsh

He said: "It was always my understanding that the artists are the copyright owners of any art they produce, irrespective of the location, and creative control over how their artwork would be used by others remains with the artist."

Why does he think street art is treated this way?

Walsh said: "In my view, this kind of case is a consequence of the perceived "coolness" of street art. Ultimately major corporations are attempting to cash in on a scene that is currently extremely popular and fashionable and in the process these companies wish to present the artists as actively complicit in such associations when they haven't been approached or consulted as to how their identity is projected.

"Essentially it is, in our view, nothing short of cultural appropriation at the individually affected artists' expense and that of the wider scenes' credibility from parties outside the subculture."

The boohooMAN campaign is not the first example of an advertising campaign using work by street artists without first seeking their permission.

In 2017 a large billboard appeared on Shoreditch High Street advertising British Airways and featured work by four different artists: German MadC, Argentinian Elian Chali, Puerto Rican Alexis Diaz and Kayleigh Doughty from the UK.

Chali was shocked to find his work being used in this way. He said: "I couldn’t believe it. I felt confused but also impotent because of the size and importance of the company."

Clear Channel, the agency who created the billboard for British Airways, said they procured the images "in good faith from reputable image libraries, and we are therefore surprised that some may have contained the works of a number of artists without their consent".

But this is not an isolated case – the appropriation of graffiti has been a major issue in the fashion industry in recent years.

Earlier this year, Swedish fashion company H&M published photos of a model wearing clothes from its New Routine line.

The shots had been taken in on a handball court in the hip Williamsburg district of Brooklyn, New York. Clearly visible behind the model was the distinctive graffiti work of LA-based artist Jason “REVOK” Williams.

When Williams asked H&M, via a cease and desist order, to remove these images their initial response was not an apology or an offer of payment. Rather, they asked a federal court to rule that Williams' work was "unauthorized and constitutes vandalism... [the] commission of illegal acts in connection with the graffiti, including criminal trespass and vandalism to New York City property, he does not own or hold any valid or enforceable copyright rights in the graffiti".

Artists took to social media to voice their concerns that this posed an economic threat, with the popular Facebook page StreetArtGlobe arguing in a post that, "if we don't take action now, many artists may find their careers and livelihoods in jeopardy".

H&M soon backed down, voluntarily dropping the lawsuit and issuing a statement in which they said they, "should have acted differently" and would be "reaching out to the artist in question to come up with a solution".

This was not the first time in which the the fashion industry has clashed with street art world. In 2015, street artist Rime alleged that a Moschino dress, designed by Jeremy Scott and worn by Katy Perry at the Met Ball, ripped off his artwork. And in 2014, Miami street artist Ahol Sniffs Glue filed a law suit against American Eagle Outfitters for copyright infringement over his “lazy eyeball” motif.

Revok demonstrates his painting technique.

The boundary between unwanted graffiti and sought-after street art is blurred. What is clearer, however, is that these artworks are perceived to have value.

In certain contexts, governments actively encourage people to unleash their spray cans onto the walls of a city.

In the UK, Glasgow City Council funds the creation of new murals on the basis that it grows the reputation of the arts community and contributes to the city’s image as a cultural centre. In Australia, Melbourne sells itself as the street art capital of the world and even funded an app to guide users around notable works in the city.

While the economic impact of street art is difficult for academics to measure, the fact that governments are willing to use public funds shows that street art is clearly believed to be worth something to locals and visitors.

Why then, is the copyright of street artists being infringed repeatedly?

Many people, including it seems large corporations, think that because street art is public it can be freely used. This is wrong.Tim Maxwell

Getting justice over copyright infringement isn't easy.

In the case of the British Airways poster in Shoreditch, the artists joined forces to seek compensation from Clear Channel, with lawyer Franco Giandana acting on behalf of the four artists.

This was not an simple task. Giandana, who is based in Argentina, had to familiarise himself with the specifics of UK copyright law and persuade London firm Boodle Hatfield to represent his clients on a no-win, no-fee basis. A financial settlement was eventually reached, but only after several months of negotiations.

Writing about the case, Tim Maxwell, an art law specialist from Boodle Hatfield, said: "Many people, including it seems large corporations, think that because street art is public it can be freely used. This is wrong."

The legal profession is aware that resolving these issues comes at a price.

What does the state of the law, paired with the very real potential for public outrage mean for fashion brands? It means you do not want to be caught with spray paint on your hands.Julie Zerbo

Tim Maxwell said: "Artists are often left in positions where they face well-resourced companies who may have copied their work. Most artists have relatively limited resources.

"Despite knowing their rights have been infringed, it may not always make sense economically to go after people who steal their images and ideas."

There is also some legal ambiguity according to Julie Zerbo, the US lawyer behind the Fashion Law blog.

In writing about the H&M case she said: "Since these cases tend to settle long before they get in front of a judge and the Copyright Act is silent on the protectability of illegally-created graffiti, we do not have a bright line rule. [But] many courts have considered (although not issued a ruling) graffiti within the realm of copyright law rather than merely tossing it aside due to the illegality factor."

While law courts have shown a willingness to place value on graffiti, companies also need to consider the court of public opinion. As Zerbo writes: "What does the state of the law, paired with the very real potential for public outrage mean for fashion brands? It means you do not want to be caught with spray paint on your hands."

American artist KAWS used an Instagram story to criticise H&M over the REVOK case

More spectacular street art

![]()

Spectacular and unusual street art in Lisbon

Alastair Sooke discovers that Lisbon's walls have become the canvas for some remarkably innovative street art.

![]()

Graffiti art on New York's subway

Henry Chalfant was a sculptor who had majored in classical Greek, who he decided to document brilliant urban art.

![]()

Art is helping Beirut recover from civil war

Jorge Rodriguez-Gerada used a shrapnel-pocked building as a canvas for a huge work in the Lebanese capital.

![]()

How graffiti grew up into giant street art

A legitimate art form? Callous vandalism? An eyesore? A new aesthetic? The evolution of the debate.

More from BBC Arts

![]()

Picasso’s ex-factor

Who are the six women who shaped his life and work?

![]()

Quiz: Picasso or pixel?

Can you separate the AI fakes from genuine paintings by Pablo Picasso?

![]()

Frida: Fiery, fierce and passionate

The extraordinary life of Mexican artist Frida Kahlo, in her own words

![]()

Proms 2023: The best bits

From Yuja Wang to Northern Soul, handpicked stand-out moments from this year's Proms