‘Always listening, always learning’: Paul Morley on the singular vision of David Bowie

27 July 2016

With a career spanning 50 years, David Bowie left behind an unparalleled cultural legacy after his untimely death on 10 January 2016. A new book, The Age of Bowie, by PAUL MORLEY, offers an account of the eclectic career of one of the 20th Century's biggest stars. Read an extract below.

The years 1947 to 2016. A strange, intense time to be alive, and to think about being alive.

From just after the end of the Second World War, when reality had been broken into pieces and needed a considerable amount of repair and realignment, through the accelerating impact of rock and roll and pop culture, to the beginnings of an emotionally violent communications revolution promising or threatening to change what it means to be human.

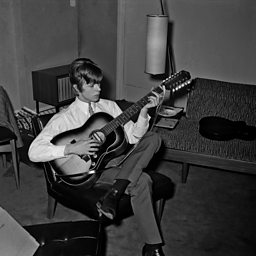

Bowie started out in music catching up with a new breed of British musicians fusing their home-grown instincts with the sound of black American blues and jazz

The internet is breaking reality into pieces, the result of a different sort of war, one that may well end up being between humans and machines – pop music created the soundtrack to this battle from the very beginning, being the result of a collaboration between humans and machines where sometimes the machines intensified the human and sometimes seemed to be taking over.

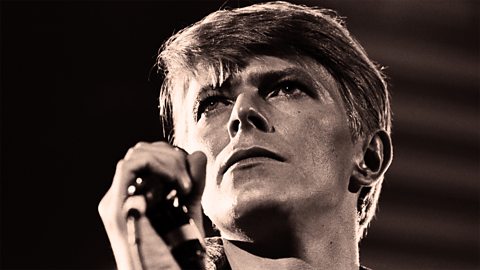

If you were in awe of the universe, all the pain and pleasure, as Bowie would admit he was, always working on his own map of its dimensions, daring to disturb it, then there was no better time to be alive, and feel its immensity and odd, intimate power, and its weird, constant presence in the mind.

Bowie started out in music catching up with a new breed of British musicians fusing their home-grown instincts and influences with the sound of black American blues and jazz, and ended it producing music as influenced as anything else by the studio methods, sonic eclecticism and conceptual playfulness of elusive, devious black entertainers like Kendrick Lamar, D’Angelo and Kanye West, whose own music and controversial public intellectual power was influenced by the generation defining shape-shifting and marketing perceptiveness of Bowie.

He had prepared the way for such a multi-layered, self-centred presentation of self, mixing the traditional with the experimental with the new- fangled and the futuristic, and a certain sort of mad, insecure ambition. He could still make the release of an album an event – especially with what came just a couple of days after its release – but not many others now could.

He knew that the release of an album had become so common, and that for those who still wanted to operate as musicians and pop stars there needed to be a new way of producing An Event, something that stood out from everything else, and got people talking about a person or group at a time when everything was being talked about and everyone was looking for attention.

He started playing home-grown skiffle on home-made instruments in post-war austerity, and ended making a sophisticated internationalist electronic music embedded in the shared Internet.

No other musician could claim to be as in the musical moment at both ends of the spectrum, to have had the artistic courage to keep up with where technology, innovations and the audience had moved over a fifty-year period, so that his music and imagery was as part of the times in 2016 as it was in the early 1970s, both commercially and creatively.

Bowie, a fan of new music from across centuries, was always listening and feeding his findings into his latest work

Blackstar was a flickering sequence of sounds, pulses, tone colours and instrumental gestures made by Bowie leading his latest Miles Davis-esque ensemble, the most orthodox jazz line-up of all, although he wasn’t making jazz but as always using its strategies to help compose songs – this collective featured New York jazz players including the pianist Jason Lindner and saxophonist Donny McCaslin.

This group knew the strained, storming blackness of Kendrick Lamar’s To Pimp a Butterfly as much as the sunshine mini-pop symphonies of Pet Sounds; its Tim Buckley, Aphex Twin, Neu!, Roxy Music, the Soulquarians, Stevie Wonder, the Necks and Godspeed You! Black Emperor as much as its Andrew Hill, Keith Jarrett, Charlie Haden and Vijay Iyer.

This was music reacting to the existence of other music from a variety of times and spaces, and reacting to how the very best music is always a matter of life and death, of keeping certain flames burning.

I’ve always found it fascinating that rock musicians who came to new music in the early 1960s and in the years afterwards mostly never seemed to move on from their original influences, so that their early work is compelling, urgent and radically new, and their later work stuck in the same place.

As Bowie found with Mick Ronson in the mid-1970s, there is an almost superstitious fear of keeping up with new music, of changing with the times, a sense of panic and despair that they have lost their original magic. Maybe most rock musicians have a year or two of youthful genius, and then the inspiration dries up and there is nothing left but repetition and nostalgia.

Bowie, a fan of new music from across centuries, was always listening and feeding his findings into his latest work. He was always learning, and always wanting everyone to learn together.

Sometimes it didn’t work, but led to something that did; for what turned out to be his last work, his closing argument, everything gels. He willed it into being as he guided the recording of the music while suffering the most punishing and dehumanising effects of chemotherapy, which apart from anything else clearly focused his mind.

‘How long?’ he once wondered, thinking about how many years he had left to live, ‘and what do I do with the time I have got left?’ He was working out the answer in his last songs.

The Age of Bowie by Paul Morley is available now, published by Simon and Schuster. Morley will discuss the book at the Edinburgh International Book Festival on 25 August.

Tony Visconti on Bowie's Heroes

Breaking down David Bowie's "Heroes" - track by track

Producer Tony Visconti uses the original master tapes to get to the heart of "Heroes".

More from BBC Arts

![]()

Picasso’s ex-factor

Who are the six women who shaped his life and work?

![]()

Quiz: Picasso or pixel?

Can you separate the AI fakes from genuine paintings by Pablo Picasso?

![]()

Frida: Fiery, fierce and passionate

The extraordinary life of Mexican artist Frida Kahlo, in her own words

![]()

Proms 2023: The best bits

From Yuja Wang to Northern Soul, handpicked stand-out moments from this year's Proms