Daniel Day-Lewis: 10 defining roles from the method master

31 January 2018

Legendary method actor Daniel Day-Lewis, who announced his retirement from the profession last summer, is being tipped for an incredible fourth Oscar at the March ceremony. Here, we look back at some of the strangest things he has done in the name of his craft.

Phantom Thread, 2017

Day-Lewis's methods have long been the subject of discussion and intrigue, and his latest role as Reynolds Woodcock, in Paul Thomas Anderson’s Phantom Thread, does not disappoint.

His co-star Vicky Krieps, who plays Alma, his on-screen lover and muse, has claimed that - at his request - she did not meet Day-Lewis until they were in character and on set shooting their first scene together.

He reportedly learned the art of dressmaking, recreating a Balenciaga dress in preparation for the role, and he is even rumoured to be leaving acting to pursue dressmaking after falling in love with the artform.

Whether the latter is a fanciful PR creation or not, it certainly fits with the public’s expectations of the actor who previously retired to Italy to become an apprentice shoemaker.

Front Row reviews Phantom Thread and Day-Lewis's career on 1 Feb 2018.

I would like to hope that he just needs a break. But I don't know. It sure doesn't seem like it right now, which is a big drag for all of us.Paul Thomas Anderson on Day-Lewis's retirement

Lincoln, 2013

Day-Lewis’s refusal to break character during filming is not a new phenomenon. While filming Lincoln he reportedly insisted that everyone on set addressed him as ‘Mr President’ - including the film’s director Steven Spielberg.

Some reports even claim that he refused to let anyone with a British accent speak to him during filming in case it broke his focus. He also only communicated to his co-star Sally Field as Abraham Lincoln, even when texting her.

There was more to his performance that maintaining character. He also studied Civil War photographs in excruciating detail and read Lincoln's letters out loud over and over again to build his character portrayal.

But all this dedication paid off when Day-Lewis won his third Oscar for his portrayal of America’s 16th President.

I never once looked the gift horse in the mouth. I never asked Daniel about his process. I didn’t want to know.Steven Spielberg

There Will Be Blood, 2007

In There Will Be Blood, another Paul Thomas Anderson project, Day-Lewis took a typically practical and hands-on approach. In preparation for his role as Daniel Plainview, a turn-of-the-century oil prospector in New Mexico, he learned to use traditional mining gear.

So intense was his portrayal that Kel O’Neill, who was originally cast to play Eli Sunday opposite him, quit the film. He was replaced by Paul Dano, at whom Day-Lewis reportedly threw real bowling balls as part of a scene.

He won his second Best Actor Oscar for the role, and the New York Times film critic Manohla Dargis raved: "It’s a thrilling performance, among the greatest I’ve seen, purposefully alienating and brilliantly located at the juncture between cinematic realism and theatrical spectacle."

There is no limit to the amount of time that you take to discover a whole life; it could take six months, a year, or a lifetime.Day-Lewis on preparation

The Ballad of Jack and Rose, 2005

When making The Ballad of Jack and Rose, in which his character Jack Slavin lived alone on an island with his daughter, Day-Lewis too lived alone in order to truly understand the isolation his character felt.

His wife, Rebecca Miller, the daughter of playwright Arthur Miller, was the director and writer of the film, and for a time during filming he lived apart from her and his children, as well as the rest of the cast and crew - reportedly sleeping in a shack two miles from the set.

On top of this, Day-Lewis also lost a tremendous amount of weight in order to capture the fragility of a dying man. Some reports at the time described the actor as "painfully thin" in the aftermath of filming.

Every actor does what he feels he needs to do to keep that reality intact, and that was his way of doing it.Rebecca Miller

Gangs of New York, 2002

For Martin Scorsese’s Gangs of New York, Day-Lewis certainly took method acting to the extreme – that is, if living apart from your wife isn’t extreme enough. He is reported to have become an apprentice butcher and hired circus performers to teach him how to throw knives.

But it doesn’t stop there. He insisted on wearing authentic period clothing for the duration of the filming, refusing to wear anything that did not exist in the 19th Century. As a result he contracted pneumonia - and then refused to take modern medicine to combat it.

Perhaps the most surprising fact of all is that he confessed to roaming about Rome, where Gangs of New York was filmed, in character, as Bill Cutting, fighting strangers.

He was a bit of a punk, a marvellous character and a joy to be – but not so good for my physical or mental health.Daniel Day-Lewis on Bill Cutting

The Boxer, 1997

Once again, Day-Lewis took a highly physical approach when preparing the character of Danny Flynn in The Boxer.

The film, by Irish director Jim Sheridan, tells the story of Flynn's attempts to go straight and overcome his IRA past after being freed from a 14-year stretch in prison.

Day-Lewis trained with former featherweight World Champion, Barry McGuigan, twice a day, seven days a week while filming - and even tattooed his own hands for the role.

McGuigan famously claimed at the time that the Hollywood star was so talented in the ring that he could have become a professional boxer, had he do desired.

If you eliminate the top ten middleweights in Britain, any of the other guys Daniel could have gone in and fought.Barry McGuigan

The Crucible, 1996

For his role as John Proctor in The Crucible, directed by Nicholas Hytner, Day-Lewis’s method madness actually benefited the crew.

He helped to build the set with traditional 17th Century tools and even lived in one of the replica homes without running water or electricity.

What the crew could have possibly done without, however, was the fact that Day-Lewis is reported not to have washed for the entire shoot in order to understand 17th Century hygiene.

So with this in mind, it's quite a surprise to think that it was on this set that he met his now wife Rebecca Miller, who was overseeing the film on behalf of the estate of her father, playwright Arthur Miller.

Daniel really does all the stuff he’s reputed to do – though he’s much more self-mocking about it than you would ever know from the way he’s written about.Nicholas Hytner

The Last of the Mohicans, 1992

Day-Lewis went native in preparation for taking on the character of Hawkeye, who was born Nathaniel Poe and later adopted by a Native American tribe, in The Last of the Mohicans, directed by Michael Mann.

He lived in the Alabama wilderness where he learnt to hunt, track and skin animals, as well as build canoes. He only ate food he had killed himself.

It is said that his flint-lock rifle was by his side the whole time during filming - including at the Christmas dinner table.

If he didn’t shoot it, he didn’t eat itMichael Mann

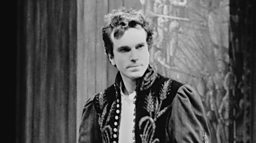

Hamlet, 1989

In this instance Day-Lewis had immersed himself so much in the tragic character of Hamlet that he collapsed in tears on stage during a performance at the National Theatre because he thought he saw his own father’s ghost.

He later explained this was more of a metaphor than a hallucination, saying: "To some extent I probably saw my father’s ghost every night, because of course if you’re working in a play like Hamlet, you explore everything through your own experience."

Regardless, the moment caused him to quit the play, leaving his understudy to complete the run. Day-Lewis even quit acting altogether for several years following the incident.

To some extent I probably saw my father’s ghost every night.Daniel Day-Lewis

My Left Foot, 1989

The character of Christy Brown, an artist with cerebral palsy, in director Jim Sheridan's My Left Foot gave Day-Lewis his first Oscar and reveals some of the methods which helped him to later success.

It is said that he would only answered to his character’s name on set. He absorbed himself so much into the role that he never left his wheelchair and was even spoon-fed by the crew.

So dedicated was he to maintaining his character's form that he apparently broke two ribs from being hunched over for such an extended time. Some reports also claim that for the opening scene of the film Day-Lewis taught himself to play a record with his toes.

Perhaps this was the role that cemented Day-Lewis’s winning formula of method madness? Or perhaps it was the first recognition of it.

Either way, this film marks the beginning of his Oscar-winning career and stands as a testament to his dedication to his craft.

Daniel spent weeks with kids who really had cerebral palsy to research the part. How difficult would it have been to act like them for the camera, then jump back after each take like nothing had happened?Jim Sheridan

Phantom Thread opens in UK cinemas on Friday 2 February 2018. Listen to Front Row’s review of the film on Thursday 1 February.

More from Front Row

![]()

Shows within shows

The animated characters who watch other shows on TV.

![]()

Podcast transitions

Can your favourite audio survive a move to the screen?

![]()

Ready to rumble?

Seven times the art world grappled with wrestling.

![]()

Apocalypse now

Seven doomed futures from E3’s hottest games.

More from BBC Arts

![]()

Picasso’s ex-factor

Who are the six women who shaped his life and work?

![]()

Quiz: Picasso or pixel?

Can you separate the AI fakes from genuine paintings by Pablo Picasso?

![]()

Frida: Fiery, fierce and passionate

The extraordinary life of Mexican artist Frida Kahlo, in her own words

![]()

Proms 2023: The best bits

From Yuja Wang to Northern Soul, handpicked stand-out moments from this year's Proms