Sing a Song of Sin

Satire in music is a rare thing. But the partnership between Kurt Weill and Berthold Brecht carved out a unique place in the history of music theatre, with works that savage as they seduce. David Kettle introduces their final collaboration, The Seven Deadly Sins.

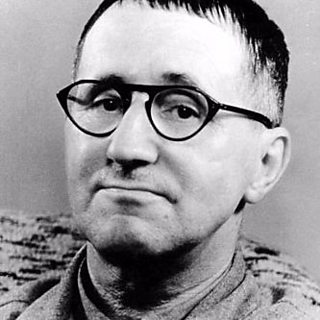

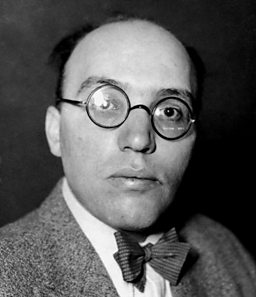

From Mack the Knife to Surabaya Johnny, the Alabama Song to the Bilbao Song, no music better epitomises the decadence, deprivation and sheer seductiveness of Germany between the two world wars than that of Kurt Weill. Working with radical playwright Berthold Brecht, and mixing up the smoky sultriness of German cabaret with the shock of radical politics, Weill summed up the despair and dreams of 1920s Germany with his Threepenny Opera, adored at its Berlin premiere in 1920, and the equally lauded Rise and Fall of the City of Mahagonny, which by its 1930 Leipzig premiere was provoking protests from Nazis in the audience.

Weill and Brecht became icons, credited with injecting vibrant new life into musical theatre worldwide, and blending acidic, jazz-inspired scores with provocative storylines that bring us up close to the exploitation of the poor and the indulgences of the rich.

Weill and Brecht became icons, credited with injecting vibrant new life into musical theatre worldwide

But although The Seven Deadly Sins shares with those earlier works Weill’s catchy, unmistakable music and Brecht’s political bite, it’s a very different beast. By 1933, the year the two men created it, the Weimar Republic was on its knees, Hitler had seized power following the (probably Nazi-initiated) Reichstag fire, and subversive German artists (especially Jews, like Weill and Brecht) who had found such a natural home in the poverty-stricken decadence of Weimar Germany had started to flee the country.

For Weill, it was to Paris, where he’d been fêted as a hero at a performance of his Mahagonny Songspiel at the end of 1932. There he met the eccentric (and frightfully wealthy) English poet, painter and philanthropist Edward James, on the lookout for new works for a new ballet company he was backing, and also hoping to rekindle his relationship with his estranged wife, dancer Tilly Losch. Weill jumped at James’s commission, persuading the reluctant Brecht to join him for one final collaboration. Together they came up with this indefinable yet fascinating work.

The Seven Deadly Sins – or, to give it Brecht’s full title, The Seven Deadly Sins of the Petty Bourgeoisie – turns Biblical teaching on its head, so that sins become virtues, and the only wrongdoing is in not committing them. It is the story of Anna I (a singer) and Anna II (a dancer, intended for Losch, but usually omitted in concert performances). They are two sides of the same person, they tell us, with ‘a single past, a single future, one heart and one savings account’, and they leave their home in Louisiana to earn cash in the US’s big cities to send to their folks back home (sung by an all-male quartet). ‘Practical’ Anna I gives the orders; pretty Anna II does what she’s told – mostly. And she’s castigated if she commits one of the ‘sins’ of the work’s title, whether that’s misplaced pride in her reluctance to strip at a Memphis cabaret, uncontrolled lust in wanting to be with the man she loves rather than the man who’ll pay for her affections, or inappropriate anger in speaking out when she sees colleagues being mistreated.

Brecht’s savage satire paints a picture of a society in which everyone and everything has its price, and in which refusing to do something you’ll be paid for – whatever that might be – is an offence against normality. And Weill’s immediately memorable music clothes Brecht’s message in the forms of popular music, with a perky foxtrot, a barbershop quartet, a heroic opera aria and a saucy waltz leaving listeners in no doubt as to the work’s message.

Despite its directness, The Seven Deadly Sins was ironically met with incomprehension at its Paris premiere in June 1933 – it didn’t help that it was sung entirely in German. But by then, resentment against the influx of refugee German intellectuals and artists to the French capital was steadily growing. At a concert later in 1933, French composer Florent Schmitt heckled Weill, shouting: ‘Vive Hitler! We have enough bad musicians in France without being sent German Jews as well!’ Two years later, Weill set sail from Cherbourg for a new life in the USA.

David Kettle is a freelance writer and critic.

More on Kurt Weill

Kurt Weill

The life and works of controversial German composer Kurt Weill.

The Seven Deadly Sins

![]()

In Concert at City Halls

Measha Brueggergosman joins Ilan Volkov and the BBC SSO on 20 October