Writing at its peak: How Nan Shepherd brought the Cairngorms to life

25 February 2015

How do words on a page bring a location alive? How can they make you see a place as you've never understood it before? Writer ROBERT MACFARLANE tells BBC Arts about Nan Shepherd's masterpiece of place-writing The Living Mountain, which takes him through the Cairngorms for a new film on BBC Four.

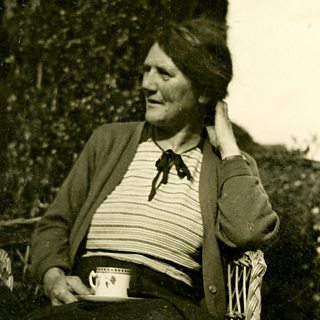

In the last months of the Second World War, a teacher called Anna ‘Nan’ Shepherd finished a short book about a place she had long loved: the Cairngorm mountains of north-east Scotland, a wild landscape of glens, peaks and storms.

Unable to find a publisher for her work, Shepherd (1893–1981) put the typescript in a drawer – and there it stayed for more than three decades, until in 1977 it was at last quietly published by Aberdeen University Press.

That book, The Living Mountain, is a slender masterpiece of place-writing, and one of the most astonishing works of landscape literature I have ever read. I thought I knew the Cairngorms well before I encountered Shepherd’s book.

I had spent nearly 20 years exploring them on foot and ski: winter-climbing in the gullies of their corries, camping out on the high tundra of their plateaux. But Shepherd’s prose showed me how little I really knew of the range. Its combination of intense scrutiny, deep familiarity and glittering imagery re-made my vision of these familiar hills. It taught me to see them, rather than just to look at them.

Shepherd’s book records – with luminous precision – details of the Cairngorm world: ‘the coil over coil’ of a golden eagle’s ascent on a thermal, a pool of ‘small frogs jumping like tiddly-winks’, a white hare crossing sunlit snow with its accompanying ‘odd ludicrous leggy shadow-skeleton’.

Her prose also rings with the joy of being in the mountains: the pleasure of drinking deeply from the ‘strong white’ water of an upland stream, say, or the feel of lying on sun-baked granite on a summer evening.

Like all great works of place-writing, The Living Mountain is utterly rooted in its chosen landscape, but also vastly expansive in its metaphysics. It is a book about the Cairngorms in the sense that Joyce’s Ulysses is a novel about Dublin, or Moby-Dick a novel about a whaling ship. Reading Shepherd, I long to be up in the hills again. But up in the hills, I feel at times as if I’m walking back into the pages of her book.

Nan Shepherd's love letter to the Cairngorms

Poet Sheena Blackhall reads from Nan Shepherd's The Living Mountain

I am far from the only person to have fallen under Shepherd’s spell. Many tens of thousands of readers have found their way to The Living Mountain in the past years: her voice speaks powerfully to us now, even across a distance of six decades. She inspires musicians, writers, artists and countless everyday walkers. As someone whose work has become entwined with that of Nan’s, I often receive letters about her. Again and again the same phrase recurs: ‘Reading The Living Mountain has changed the way I see…’.

In 2009 – inspired in part by another classic of place-literature, J.A. Baker’s The Peregrine (1967) – I made a Natural World film for BBC2 called The Wild Places of Essex, which sought to find and celebrate the remarkable ‘modern nature’ of that much-maligned county.

My hope was that it might change in some measure the ways we imagine the landscape of Essex, and of south-east England more generally. The programme was an hour long, but took almost a year in the field to film.

And last October, just as winter was tightening its grip upon the Highlands, I travelled to the Cairngorms to make a Secret Knowledge programme about Nan and the range. The film adapted a chapter of a book of mine called Landmarks, which explores the huge power of language – single words, strong style – to shape our sense of place.

We filmed it over three unforgettable days, coping with wind-chill, flying ice splinters and thick mist – but rewarded by sudden clearings in the clouds, and sun-squalls that set the mountains shining for miles around.

At one point in The Living Mountain, Shepherd uses the fabulous Scots term ‘roarie bummlers’, which sounds like a group-noun for a crowd of public schoolboys, but in fact means ‘fast-moving storm clouds’. Well, on our final afternoon’s filming, the roarie bummlers were out in force. Coming down at dusk off the summits, back to our high camp at 2500 feet, we found that the rising gale had pancaked our tents flat to the ground.

There was nothing for it but to pack up all our gear, and hump it out for five miles to the shelter of the ancient pine forest on the north slope of the range. It was tough going, at the end of a long day. But even on that heavy-packed route march, I couldn’t stop grinning in the darkness, happy just to be up there, among the living mountains.

Secret Knowledge: The Living Mountain is on BBC Four at 20:30 on Wednesday 25 February 2015.

The Living Mountain

![]()

Secret Knowledge

Robert Macfarlane retraces Nan Shepherd's footsteps in the Cairngorms through her writing

Literary landscapes

Robert Macfarlane chooses three more must-read classics of place-writing:

J A Baker, The Peregrine (1967)

Baker’s cult book – written in a style of flaring intensity – draws on the decade that he spent tracking the peregrines of Essex. His writing makes Essex seem as strange and wild as the Karakorum or the Antarctic.

Tim Robinson, the Connemara trilogy (2006–2011)

Robinson has spent forty years and thousands of pages deep-mapping the landscapes of the west of Ireland, with a fine-grained attention to the interplay of humanity and geology. His work constitutes perhaps the most remarkable project of place-writing in contemporary literature.

Barry Lopez, Arctic Dreams (1987)

Lopez’s dazzling book combines cultural history, anthropology, and lyrical prose-poetry to evoke the wonders and complexities of the Canadian Arctic.