The Faerie Queene: Arthurian legend or author’s demise?

12 October 2015

As part of the BBC's Contains Strong Language poetry season, The Secret Life of Books is looking at Edmund Spenser's Elizabethan epic The Faerie Queene, revealing how this fantasy world of elves, nymphs and questing knights was written in the midst of the brutal Tudor occupation of Ireland, and how the writer's growing disillusionment with the conflict was coded into the poem's restless verse. Here, presenter DR JANINA RAMIREZ writes for BBC Arts on how the poem reflects Spenser's own unravelling while heralding the start of a new way of writing.

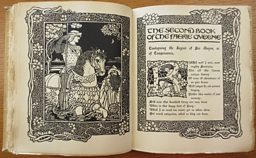

Many people claim to have read The Faerie Queene by Edmund Spenser, but most haven’t read it cover to cover. I have. As one of the longest poems ever written in the English language, this was no mean feat.

It is a classic, cropping up on the majority of undergraduate reading lists on English degree courses across the country, and cited as one of the most important texts of the Elizabethan period. Yet I know from my fellow undergraduates at Oxford that most skim read a bit, skip to the Mutabilitie Cantos, and cut out the many complicated quests and allegorical characters in between. But for me, that was the attraction!

I read The Faerie Queene not for what it told me about Elizabethan literature, but the light it shone back on centuries of medieval texts

I’m a medievalist, and I read The Faerie Queene not for what it told me about Elizabethan literature, but the light it shone back on centuries of medieval texts. I devoured every word, soaked up every stanza, and years later it continues to excite and inspire me.

It lay at the heart of my undergraduate dissertation. In true medieval form I wanted to examine the legends of King Arthur, so started with Layamon’s Brut, moved through Malory’s Morte D’Arthur, and concluded with Spenser’s Faerie Queene.

In this context I saw the poem not as something new and innovative, but as the rather tired close to centuries of courtly love poetry. The final curtain call of a medieval literary genre.

The legends of King Arthur and his knights of the Round Table provided a secular equivalent to the heroic saints venerated by medieval Christians. The knights, lords and ladies of powerful courts were provided with clear exemplars of the most valued virtues, and they could celebrate, condone or condemn the heroes and heroines of courtly love literature.

These medieval texts were an essential part of morally conditioning an armoured class to adhere to Christian ideals. When knights were trained from childhood to be merciless killers on the battlefield, endowed with expensive armour and weapons, then given free reign to take whatever came their way (including women), courtly love poets would try to temper their excesses with the example of ‘perfect’ knights. The characters in Malory’s Morte D’Arthur could win a quest, defeat a dragon, or conquer lands, but they never looted, raped or pillaged.

This was how I originally read The Faerie Queene. But the more I read, the more I realised that everything in this epic poem is a paradox. Last of the courtly love poems, yet first English epic; last text focused exclusively on allegory, yet first to present contemporary politics in its infinite complexity; last of the medieval poems, and first to employ the incredibly complex Spenserian stanza, which would go on to inspire poets up to the present day. It charts the end of so much, yet the beginning of an entirely new way of writing.

And what really struck me as I have returned to the poem more recently, was that the collapse of the established medieval courtly love genre coincides with the collapse of the Tudor dynasty, and of Spenser himself. The Faerie Queene is tragic.

When Spenser wrote his Letter to Walter Raleigh, which acts as a Preface to the text, his vision and idealism were clear. "The general end therefore of all the booke is to fashion a gentleman or noble person in virtuous and gentle discipline." He would use "continued Allegory" to present 24 virtues, and at the heart were the perfect examples of Magnificence in King Arthur, and Glory in the Faerie Queene herself – Gloriana as Elizabeth the first.

This was a bold quest Spenser embarked on; attempting to condition the moral fabric of his society, and providing a blueprint for the perfect nobleman or woman. But on the brink of the modern world, set against the backdrop of the Reformation and Spenser’s own disastrous involvement with the Plantation projects in Ireland, this idealistic project was on a course of self-destruction.

The moral fabric of the medieval world, with its plethora of symbols, allegories, saints, heroes and legends, was gradually unpicked in post-Reformation Britain. A new world of moral ambiguity – closer to our modern world – was opening up before Spenser, and despite his attempts to cling to a simpler example from the past, he couldn’t ignore its impact.

If you have read The Faerie Queene, then read it again. And if you’ve never read it, then what are you waiting for?

The Faerie Queene charts Spenser's own moral, intellectual and emotional unraveling. The first books emphasise the perfection of the protagonists, and quests are fought and won.

However, as Spenser encountered more and more frustration and tragedy in his own life, culminating in the siege of his lands and death of a son in Ireland, the poem moves away from any conclusion.

Instead, like the Spenserian stanza itself, with its open final lines removing resolve in each instance, the poem itself could never end. It remains unfinished.

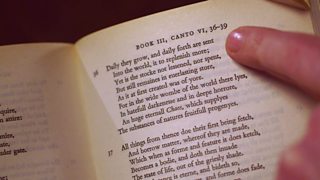

Instead of a happy ending, the poem closes with the Mutability Cantos. In my opinion these are some of the most moving, disturbing and powerful stanzas penned in the English language. In this stanza Spenser laments how everything is unpredictable apart from the mutability of life. Everything; justice, politics, right and wrong, they can all be subverted, and all that remains is death:

“Ne shee the laws of Nature onely brake,

But eke of Iustice, and of Policie;

And wrong of right, and bad of good did make,

And death for life exchanged foolishlie:

Since which, all liuing wights haue learn’d to die,

And all this world is woxen daily worse.

O pittious worke of Mutabilitie!

By which, we all are subiect to that curse,

And death in stead of life haue sucked from our Nurse.” (Canto VI, stanza 6)

If you have read The Faerie Queene, then read it again. And if you’ve never read it, then what are you waiting for? It is England’s epic. To read it is to begin to understand one of the most important moments in this nation’s history, and one of its most influential poets. It is also something that will move you to your core.

The Secret Life of Books: The Faerie Queene is on BBC Four on 13 October.

Watch the show

![]()

The Secret Life of Books:The Faerie Queene

On BBC Four, 12 October 2015, 20.30, and on BBC iPlayer for 30 days thereafter.

Watch clips

Dr Janina Ramirez unpicks the hidden meaning behind Edmund Spenser's The Faerie Queene.

As war closes in around him, Spenser's life and work comes to a dramatic climax.

Dr Simon Palfrey explains what lies behind Edmund Spenser's restless poetic technique.

Related Links

Poetry season

![]()

Contains Strong Language

A major season centred around National Poetry Day on 8 October 2015.

More from BBC Arts

![]()

Picasso’s ex-factor

Who are the six women who shaped his life and work?

![]()

Quiz: Picasso or pixel?

Can you separate the AI fakes from genuine paintings by Pablo Picasso?

![]()

Frida: Fiery, fierce and passionate

The extraordinary life of Mexican artist Frida Kahlo, in her own words

![]()

Proms 2023: The best bits

From Yuja Wang to Northern Soul, handpicked stand-out moments from this year's Proms