Paramilitary to pop culture: The changing face of Belfast’s murals

9 April 2018

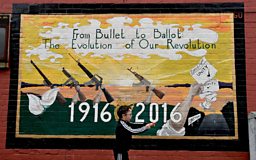

Two decades after the Good Friday Agreement, the murals of Northern Ireland remain a window onto the country's political ideologies. WILLIAM COOK charts the shift from street art as paramilitary propaganda to a celebration of culture.

Twenty years ago, on 10th April 1998, the British Prime Minister, Tony Blair, and the Irish Taoiseach, Bertie Ahern, signed the Good Friday Agreement which laid the foundations for lasting peace in Northern Ireland.

That peace has been imperfect, marred by some terrible atrocities, but since Good Friday 1998 paramilitary activity in Northern Ireland has been the exception, not the rule. A conflict which claimed more than 3,000 lives largely ended 20 years ago, yet its artistic legacy remains.

The conflict in Northern Ireland has been mapped out in the murals on its gable walls

Ever since the beginning of ‘The Troubles’, half a century ago, the conflict in Northern Ireland has been mapped out in the murals on its gable walls. Nationalist and Unionist murals are part of the cityscape of Northern Ireland, particularly in Belfast and Londonderry.

It’s a unique art form, dynamic and disquieting, and 20 years since the Good Friday Agreement it continues to reflect the troubled politics of Northern Ireland.

Painting murals in Northern Ireland was originally a Unionist tradition, which predated the partition of Ireland in 1921. For Unionists, who supported the union of Britain and Ireland, the most important day in their history was 12 July 1690, when the Protestant King William III defeated the Catholic King James II at the Battle of the Boyne. For Unionists, 12 July remains an annual day of celebration. Since the early 1900s streets in Protestant areas have been decorated with murals of ‘King Billy.’

For Irish Nationalists, mural painting only began in 1981, in support of Republican inmates in British prisons who went on hunger strike to demand special status as political prisoners.

One of these hunger strikers, Bobby Sands, was elected as a Member of Parliament for Sinn Fein shortly before he died, propelling the party into mainstream politics. From then on, murals became the billboards of the Republican campaign.

If Nationalist and Unionist murals had remained static, they’d only be of finite interest. What makes them so engrossing is the way they’ve changed with the times, reflecting – and sometimes shaping – the changing political situation.

After the Anglo-Irish Agreement of 1985, which hardline Unionists regarded as a betrayal, Unionist murals emphasised the heraldic links between Northern Ireland and Great Britain. Nationalist murals adopted a more internationalist position, claiming equivalence with independence movements in the Basque Country and Palestine.

What makes them so engrossing is the way they’ve changed with the times

For Republicans (who sought the incorporation of Northern Ireland into the Irish Republic) and Loyalists (who proclaimed their loyalty to the United Kingdom), the 1994 ceasefire presented contrasting challenges.

As Sinn Fein broadened its appeal at the ballot box, Republican muralists focused on the more political aspects of Republicanism, criticising the British government rather than celebrating the armed struggle.

Loyalists, conversely, were keen to reassure their supporters that they hadn’t sold out to the IRA. Consequently, Loyalist murals became more militaristic.

Yet since the Good Friday Agreement, things have begun to change. In 2000, I returned to Northern Ireland, for the first time since the ceasefire, to meet two muralists who’d agreed to share a conference platform at Belfast’s Ulster Museum. Danny Devenny was a former Republican prisoner; Noel Large was a former Loyalist prisoner. Their joint participation showed what efforts old foes were making to find some common ground.

During that visit, I toured the Catholic and Protestant heartlands of Belfast with Bill Rolston - the author of several books about these murals, and now Emeritus Professor of Sociology at Ulster University. I’ve been back half a dozen times since then, and each time I’ve sensed a subtle shift in what Rolston calls this ‘barometer of political ideology.’

For a long time, Republican murals have focused on Irish culture rather than paramilitary activity, and lately Loyalist muralists have started to catch up. Several Loyalist murals, painted soon after the Good Friday Agreement, celebrated Ulster-Scots heroes of 19th Century America, like Davy Crockett, and James Buchanan, 15th President of the United States.

For outsiders, Republican and Loyalist murals present a fascinating picture of how two communities, living side by side, can have such a different sense of history.

Both communities paint murals commemorating 1916, but while Republicans paint the Easter Rising, Loyalists paint the Battle of the Somme. Loyalists paint the Relief of the Siege of Derry; Republicans paint Wolf Tone. Both communities paint the Irish mythical hero, Cuchulainn, but Republicans depict him as an Irish Nationalist, while Loyalists depict him as a patriotic Ulsterman, defending Ulster against Celtic invaders.

![]()

Political murals

Professor Bill Rolston, author of 'Drawing support: murals in Northern Ireland' discusses the significance, artistry and legacy of political murals in Northern Ireland.

The Arts Council of Northern Ireland has spent several million pounds removing supposedly offensive murals (often of armed men in balaclavas) and replacing them with murals of cultural and sporting figures.

In 2007, Danny Devenny teamed up with Mark Ervine, son of the late Loyalist leader David Ervine, to paint a copy of Picasso’s Guernica on the Catholic Falls Road. Yet in 2013, a mural of George Best, supported by a grant from Belfast City Council, was replaced by a mural of a masked gunman from the Ulster Volunteer Force.

Muralists like Danny Devenny and Mark Ervine have made huge strides towards a shared identity in Northern Ireland. But on the gable walls, as in Stormont, there’s still a long way to go.

Murals in the news

![]()

Suicide awareness

Fifteen football clubs feature on the Suicide Awareness and Mental Health Initiative mural.

![]()

Same-sex marriage

Street artist Joe Caslin painted the mural as part of the same-sex marriage campaign.

More from BBC Arts

![]()

Picasso’s ex-factor

Who are the six women who shaped his life and work?

![]()

Quiz: Picasso or pixel?

Can you separate the AI fakes from genuine paintings by Pablo Picasso?

![]()

Frida: Fiery, fierce and passionate

The extraordinary life of Mexican artist Frida Kahlo, in her own words

![]()

Proms 2023: The best bits

From Yuja Wang to Northern Soul, handpicked stand-out moments from this year's Proms