Daring DIY: How pioneering artist Robert Rauschenberg broke down barriers

1 December 2016

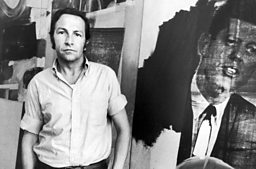

Across a six decade career, Robert Rauschenberg blazed a trail in Pop Art, Abstract Expressionism, performance art – and choreography. WILLIAM COOK visits Tate Modern for the first major exhibition for 35 years of a man who helped shape the art world of the 1960s.

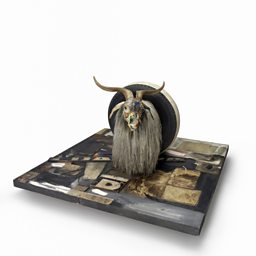

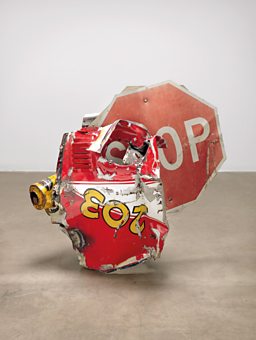

"A picture is more like the real world when it’s made out of the real world," said Robert Rauschenberg, and this thrilling exhibition, at London’s Tate Modern, shows exactly what he meant.

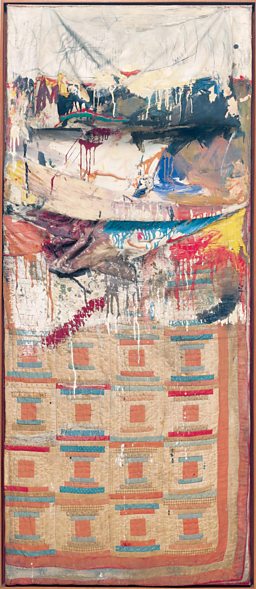

He could make art out of anything – household junk, old clothes, scrap metal – and his do-it-yourself artworks made him one of the most influential artists of modern times. "He opened the door," says Frances Morris, director of Tate Modern. "Tracey Emin couldn’t unmake her Bed without Rauschenberg making his."

I want my paintings to look like what’s going on outside my window, rather than what’s inside my studioRobert Rauschenberg

Like a lot of his best artworks, Rauschenberg’s Bed came about by accident. He wanted to do a conventional painting but he couldn’t afford a canvas, so he used an old quilt instead.

He liked the way it looked, so he added a pillow and a bedsheet. He painted it and framed it and hung it on the wall.

The way this work evolved sums up his happy-go-lucky attitude. Throughout his long life, he was always willing to give anything a go.

Robert Rauschenberg was born in 1925, in Texas. He didn’t think of becoming an artist until he paid his first visit to an art gallery, while serving in the US Navy.

He went to study art in Paris, where he met the American artist Susan Weil. When Susan returned to America, to study at Black Mountain College, Rauschenberg went with her. This radical institution inspired him to become a different sort of artist, an artist indifferent to conventional notions about making art.

With Weil, he moved to New York, and started making art out of everyday objects. "I want my paintings to look like what’s going on outside my window, rather than what’s inside my studio," he said.

Robert and Susan had a child together, called Christopher. I met up with Christopher at Tate Modern to ask him about his dad.

"To me, the thing that was most distinctive about my father was the unbelievable level of curiosity that he had," says Christopher. "Once he knew what he was doing, it was time to do something else."

Rauschenberg broke down the barriers between painting, sculpture and performance. Rather than sticking to one style, he was forever searching for something new. When Abstract Expressionism was all the rage, he became a pioneer of Pop Art. When Pop Art was the height of fashion, he started doing stage design instead.

His entry into performance art was another lucky accident. He was making sets for a dance company when he was wrongly credited as a choreographer. OK, he thought, let’s give choreography a go. The result was Pelican, a surreal performance for dancers on rollerskates, with parachutes.

Rauschenberg was one of the dancers. Yes, it was daft – of course it was - but it was also terrific fun. He had a great sense of humour. He sometimes painted onstage, with an alarm clock, before an audience. When the alarm went off, the painting was done.

Rauschenberg wasn’t just a prankster. He made artworks of great power and beauty

Some of his conceptual stunts challenged the very idea of art. In 1953, when he was still unknown, he asked one of America’s most famous artists, Willem de Kooning, to make a picture simply so that Rauschenberg could erase it. Luckily, De Kooning saw the funny side.

He drew a picture for Rauschenberg which was almost impossible to erase. Undeterred, Rauschenberg spent a month (and many rubbers) erasing it. The result, a blank sheet of paper, has pride of place in this show.

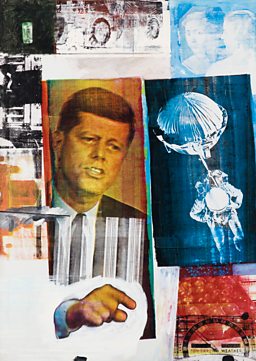

However Rauschenberg wasn’t just a prankster. He made artworks of great power and beauty, like Retroactive II, his iconic portrait of President Kennedy.

He started working on this montage when JFK was alive. By the time he’d finished, JFK had been assassinated. The resultant picture was one of the defining images of the age.

Rauschenberg’s can-do approach epitomised the optimism of the 1960s, yet his artworks often portrayed that decade’s darker side. The collage he made for Time magazine focused on the tragic figures of the Sixties: Janis Joplin, Robert Kennedy, Martin Luther King… Time rejected it. Not for the first time, or the last, Rauschenberg was ahead of his time.

Rauschenberg was so versatile that this one man show seems more like an ensemble show by a dozen different artists. He believed art should be a team sport. He was always eager to work with other artists; always happy to share ideas.

Even in his old age, he was still innovating, still sharing. He travelled all around the world, staging exhibitions on several continents. He embraced new technology, experimenting with computer art.

Right up until his death, in 2008, Rauschenberg maintained an interest in younger artists, and a childlike wonder about the world around him. His career was an object lesson in how an artist should live and work.

Christopher sums up his dad’s attitude - to art, and life. "Hey, look, here’s something I figured out! There’s a lot of good stuff over here! You guys work on it! I’m going to go see if there’s another door down the hall."

The Robert Rauschenberg exhibition is at Tate Modern from 1 December 2016 to 2 April 2017.

Music at the Tate

![]()

Radio 3: Morton Feldman live from the Tate, midnight Saturday, 3 Dec 2016

A close friend of Rauschenberg, Feldman's 2nd String Quartet gets a live performance at Tate

Modern and performance art

More from BBC Arts

![]()

Picasso’s ex-factor

Who are the six women who shaped his life and work?

![]()

Quiz: Picasso or pixel?

Can you separate the AI fakes from genuine paintings by Pablo Picasso?

![]()

Frida: Fiery, fierce and passionate

The extraordinary life of Mexican artist Frida Kahlo, in her own words

![]()

Proms 2023: The best bits

From Yuja Wang to Northern Soul, handpicked stand-out moments from this year's Proms