How Frankenstein and his Creature conquered the movies

31 December 2017

On New Year’s Day 2018, Frankenstein turns 200. Amazingly, Mary Shelley’s creature has spent the last century as a movie star. CHRISTOPHER FRAYLING recounts the story of the monster and his creator and selects seven of the best Frankenstein films.

On New Year’s Day 1818, Mary Shelley’s novel Frankenstein was first published in an anonymous three-volume edition of 500 copies. She was eighteen years old when she had the original idea, nineteen when she expanded it into a novel and twenty when it came out.

Of the reviews which appeared in 1818, most were unfavourable (they thought the book too unpleasant or too radical in implication) but Walter Scott, in one of the few favourable ones, concluded that Mary Shelley had invented a new literary genre, which took existing science and wove ‘new trains and channels of thought’ around it - today we’d call this science fiction.

But, at a time when the concept of intellectual property had yet to be invented, it was the many unauthorised and stripped-down theatrical adaptations rather than the novel itself which launched the F- word into the cultural bloodstream: by 1826, at least fifteen English and French versions or burlesques had opened.

Then, in the early 1900s, it was the turn of cinema, with Victor and his creature eventually becoming, with Sherlock Holmes and Dracula, the most-often filmed literary characters of all...

Frankenstein, 1910

Frankenstein's silver screen debut is the first horror movie

This early one-reeler, made for the Thomas Edison Film Company, long thought lost until rediscovered in the 1970s, is the earliest film version of Frankenstein and, some claim, the first American horror movie with a story worthy of the name.

It provides a direct link with the theatrical versions of Mary Shelley’s novel which proliferated on the stage in the nineteenth century. The creation scene involves a bubbling pot which transmutes a skeleton into a hideous figure with bulbous eyes, a misshapen body and frizzy hair—achieved by setting a skeleton on fire and running the resulting film backwards.

Edison’s publicity stressed that the film-makers had ‘carefully tried to eliminate all the actually repulsive situations and to concentrate upon the mystic and psychological problems that are to be found in this weird tale’. One clever touch had the scientist looking into a mirror and seeing the Monster. A horror film before horror became a genre.

Frankenstein, 1931

The Universal Studios classic that launched a 1000 imitations

This created the definitive movie image of the mad scientist and his monster, and in the process launched a thousand imitations: all subsequent film versions of Mary Shelley’s novel have had to take into account how their plot, characterisations and make-up conform to or differ from the Universal Studios template.

It took two directors (Robert Florey, then James Whale), two creatures (Bela Lugosi, then Boris Karloff), five or more screenwriters and two possible endings (one where the scientist survives, the other where he perishes) to create this film, and in the process there were many changes to Mary Shelley’s original novel: the monster (Karloff) was childlike and grunting and had an ‘abnormal brain’ as well as an enlarged cranium; the period was a strange mixture of medieval, romantic Gothic and the present day; the scientist (Colin Clive) had an elaborate and fully-equipped laboratory; and the film successfully fused German Expressionism with American carnival.

A classic. Depression-era audiences loved its attacks on experts.

The Bride of Frankenstein, 1935

Whale and Karloff reunite for swaggering sequel that launched a franchise

Four years in gestation, and originally entitled The Return of Frankenstein, this reunited the Frankenstein team of director James Whale, actors Boris Karloff, Colin Clive and Dwight Frye, and the designers, to create a sequel which had a bigger budget, a wittier script, a new musical score and much more confidence.

To a new world of gods and monstersDr. Praetorious to Dr. Henry Frankenstein

It also added a rival scientist in the form of the high-camp Dr Septimus Pretorius (Ernest Thesiger), a hissing bride (Elsa Lanchester) whose make-up resembled the recently discovered ancient Egyptian portrait bust of Nefertiti, and a cheeky prologue in which Percy Shelley said to Mary that it was a shame her story of Frankenstein had ended quite so suddenly - to which she replied, ‘Oh no, that wasn’t the end at all.’

The title confused the scientist with his creature, as did Lord Byron in the prologue, and Bride made less money than its predecessor, but it is more fun than the 1931 Frankenstein and it launched a franchise.

James Whale's inspiration for the Bride was Maria, the artificial woman from Fritz Lang's Metropolis,1927.

The Curse of Frankenstein, 1957

Britain’s Hammer Films reclaims Frankenstein

Britain’s Hammer Films started a new tradition with this - in colour for the first time, with a repressive Victorian setting, more gore, a new repertory company of actors, and a focus on Baron Victor Frankenstein rather than on the Monster.

Peter Cushing played the scientist as elegant, ruthless and arrogant - a mature figure, unlike the young research student of the novel - while Christopher Lee’s brutish and cadaverous Monster was covered in scars and transplanted tissue (Karloff-style makeup had been copyrighted). Other innovations included a cynicism about the establishment and its destructiveness, and a critique of Victorian values.

Some reviewers at the time were appalled - suggesting the film should be given a ‘SO’ certificate: for Sadists Only. Its commercial success in the UK and America founded the Hammer House of Horror brand and led to six sequels (usually with an increasingly nasty-seeming Cushing) between 1957 and 1973. Frankenstein had been reclaimed by Britain.

Young Frankenstein, 1974

‘That’s Fronkensteen': Mel Brooks' hilarious homage to 1930s Hollywood

An affectionate, monochrome homage / parody of the old Universal Studios Frankenstein - especially Son of Frankenstein (1939).

It has Peter Boyle channelling Boris Karloff; it reassembles the original laboratory equipment from the 1931 version, discovered in a storeroom; it features Marty Feldman as hunchbacked assistant Igor and Madeline Kahn as the scientist’s fiancée / the Bride; and has Dr Frederick Frankenstein (Gene Wilder - ‘That’s Fronkensteen’) memorably performing, with his creature, the Fred Astaire number Puttin’ on the Ritz in white tie and tails.

Mel Brooks, who co-wrote the often hilarious script with Gene Wilder and who also directed, said of the film - tongue firmly in cheek: ‘It’s about womb-envy, and the mob’s ignorance and fear of genius. So it’s a very Promethean work...’

The look of the film successfully evokes 1930s Hollywood. Young Frankenstein was transformed by Brooks into a stage musical in 2007, with a revised version in 2017. Uniquely, the film has a happy ending - the Monster settling down with Frankenstein’s ex.

The Rocky Horror Picture Show, 1975

King of midnight movies that launched 'Shadow Cast' audience participation

Based on Richard O’Brien’s cult stage musical and directed by Jim Sharman, this riotous film presented the clichés of horror movies - Universal and Hammer - as if they were an alternative sexual universe, as ‘sweet transvestite from Transexual, Transylvania’ Dr Frank N. Furter (a well over-the-top Tim Curry) unveils his latest creation, the beautiful blond and muscular Rocky Horror in a silver loincloth.

Here, the flirtation of the horror movie - since its origins - with subversion, transgression and ‘the other’ has moved joyously centre stage, and becomes the point of the story. O’Brien was the seedy butler Riff Raff, and Peter Hinwood the hunky peroxided creature. By now, it was becoming difficult to tell the old Frankenstein story without sending it up or treating it as camp.

This film launched the craze for ‘dressing up’ or ‘cos-play’ immersive cinema, with the audience joining in.

Mary Shelley's Frankenstein, 1994

Mary Shelley's creation receives the Kenneth Branagh treatment

The most elaborate version to date, with a $45 million price tag—and the only Frankenstein to be nominated for an Academy Award (makeup) - this film, directed by and starring Kenneth Branagh, really did attempt to be faithful to the notoriously difficult to adapt original novel (complete with framing device, set in the frozen Arctic).

It cleverly treated the creation scene as a laboratory birth - gigantic bellows ejaculating electric eels into a womb-shaped vat full of amniotic fluid; the creature (Robert De Niro) as grown-up baby - and suggested that part of Victor Frankenstein’s motivation was his own anxieties about childbirth, having seen his mother die while delivering his younger brother.

Clearly, the scriptwriters had been reading the latest biographies of Mary Shelley. Handsomely mounted and well-acted, as much costume drama as horror film, this film seemed to confuse critics and audiences because it didn’t conform to the age-old conventions of Frankenstein films. Too much prestige.

About Christopher Frayling

Sir Christopher Frayling is a recognised authority on Gothic fiction and horror movies (as well as spaghetti westerns). His study of Vampyres (1978, 1990, 2016) and his four-part BBC One series Nightmare: The Birth of Horror (1996) have helped to move Gothic horror from margin to mainstream. He is a former Chairman of Arts Council England.

Frayling's book, Frankenstein: The First Two Hundred Years (Reel Art Press), celebrates the two hundredth birthday of Shelley’s Frankenstein.

More Frankenstein

![]()

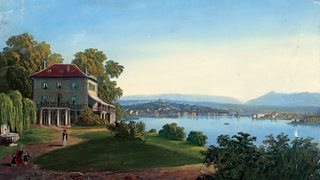

Freak events that gave birth to a masterpiece

BBC Arts goes to the source of Frankenstein on the shores of Lake Geneva.

![]()

Tim Burton's Frankenweenie

Tim Burton's stop-motion animation take on Frankenstein. Showing on BBC Two and BBC iPlayer, New Year's Day 2018.

![]()

The Strange Affair of Frankenstein

BBC Four Gothic Literature collection: Investigating the background to Mary Shelley's Frankenstein.

![]()

The house where Frankenstein was born

Professor Alice Roberts visits Geneva and the house where Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein was born.

More from BBC Arts

![]()

Picasso’s ex-factor

Who are the six women who shaped his life and work?

![]()

Quiz: Picasso or pixel?

Can you separate the AI fakes from genuine paintings by Pablo Picasso?

![]()

Frida: Fiery, fierce and passionate

The extraordinary life of Mexican artist Frida Kahlo, in her own words

![]()

Proms 2023: The best bits

From Yuja Wang to Northern Soul, handpicked stand-out moments from this year's Proms