Wrap stars: Christo and Jeanne-Claude's 50 years of pop-up art

26 January 2018

Artists Christo and Jeanne-Claude wrapped the Reichstag, trees and even coasts in shimmering fabric, and allowed people in Italy to walk on water. As Brussels welcomes a show of original work, WILLIAM COOK explores one of the most remarkable partnerships in modern art.

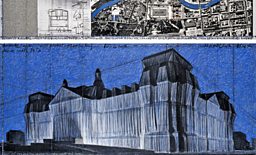

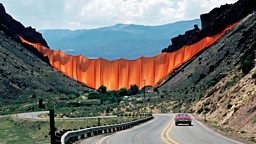

He wrapped up the Reichstag in Berlin and the Pont Neuf in Paris. He hung a curtain across a valley in Colorado. He’s wrapped eleven islands in Florida and a stretch of coastline in Australia. No artist has ever worked on a more monumental scale than Christo, and now you can see one of his earliest works, in Brussels, at BRAFA, the city’s annual art fair.

Many of his projects have been years, even decades in the making. So who is Christo? Why does he do it? And what on earth does it all mean?

Three Store Fronts was first exhibited in the Netherlands in 1966. At the Van Abbemuseum in Eindhoven, Christo draped three shop windows with white sheets, creating an enigmatic work of art out of these prosaic, familiar objects.

Compared to his later work, it’s tiny – fourteen metres long and 2.5m tall – but it’s still the largest artwork ever exhibited at BRAFA.

Like so many of his artworks, it’ll be all gone in a week or two, yet many of his projects have been years, even decades in the making. So who is Christo? Why does he do it? And what on earth does it all mean?

Art critics have spent half a century trying to understand Christo, but the wonder of his art is that there’s really nothing much to understand. His artworks are like works of nature – inspiring, uplifting, but utterly devoid of meaning.

There’s no hidden message. You can make of them what you will. For me, it’s enough to stand and stare at them, and marvel at their abstract beauty.

Valley Curtain, Rifle, Colorado, 1970-72

Yet like all great art, his work does something else, something that stays with you. His artworks make you see the world around you in a slightly different way. Familiar landmarks acquire a new significance. They become sculpture, rather than architecture. The surrounding landscape changes ever so slightly. The world becomes even more beautiful than before.

I love the reality! I don’t like to see a photographic image, or a film – I like to have the real thing.

Well, that’s my take on it, anyway, and if Christo disagrees with me he’s not saying. ‘The work can absorb all kinds of interpretations, and all these interpretations are legitimate,’ he says, on the phone from his home in New York.

He calls his work ‘irrational, irresponsible, useless,’ and it’s hard to disagree. Although his artworks are usually only displayed for a few weeks, and then dismantled, their preparation (what he calls the Software Period) can take decades, and the maestro behind these ‘Software Periods’ was his beloved wife, Jeanne-Claude, the other half of his creative team.

Christo Javacheff and Jeanne-Claude de Guillebon were born on the same day, 13th June 1935, several thousand miles apart. Christo was born and raised in Bulgaria, Jeanne-Claude in Casablanca. His father was a businessman, her father was a soldier. She studied in Tunisia and then moved to Paris, where she met Christo, in 1958.

Christo arrived in Paris by a more roundabout route. A gifted artist from an early age, he studied art in Bulgaria, then went to Prague, then fled to Vienna. From Vienna he went to Geneva, and then on to Paris. He was scratching a living as a portrait painter when he met Jeanne-Claude (he’d been hired to paint her mother). It was love at first sight.

Wrapped Trees, Switzerland, 1997-98

Christo took her to his attic studio, to show her his sculptures – household objects, all wrapped up. She’d never seen anything like it, and she loved it. She was already married, but she left her husband for him. In 1960, they had a son together. From then on they were inseparable, right up until her death, from a brain aneurysm, in 2009.

Christo took Jeanne-Claude to his attic studio, to show her his sculptures – household objects, all wrapped up. She’d never seen anything like it, and she loved it.

In 1961, the Berlin Wall went up and Christo was aghast. He’d fled the Communist bloc to find freedom. Now countless other artists were trapped behind the Wall. He responded by building a wall of oil drums, across the Rue Visconti in Paris. ‘My Iron Curtain was a curtain of art.’

In 1964, the couple moved to New York, which became their lasting home. ‘I love New York – the architecture, the people, the space,’ he says, from his adopted home in Manhattan. ‘Nobody cares where you come from.’ He’s lived in the same industrial building in SoHo ever since 1964.

Jeanne-Claude was a tireless champion of Christo’s work, but she subjected his ideas to fearless scrutiny. ‘She was very critical,’ he says. ‘Each time we’d do something, she would argue and argue. “Why should we do it that way, and not another way?” She was really very challenging.’ This was exactly what he needed. She was a crucial sounding board for his ideas.

She was also a brilliant administrator. Thank to her genius for organisation, Christo moved on to wrapping buildings, but though these are his most famous works, he’s done all sorts of other things besides.

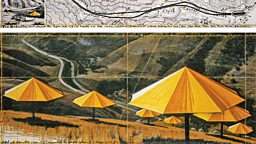

One of his finest creations was an instillation of huge umbrellas in two valleys an ocean apart – 1,760 yellow umbrellas in California, and 1,340 blue umbrellas in Japan. ‘We never do the same thing again - each project is totally different,’ he says. ‘Each time is a new adventure, a new journey – it’s like an expedition.’

The Umbrellas, Japan-USA, 1984-91

Such schemes are horribly expensive, but to preserve their creative integrity, they never accepted any sponsorship or commissions. ‘I’m very stubborn,’ he says. They raised funds by selling Christo’s preparatory sketches, which are artworks in their own right.

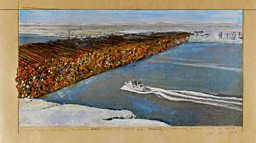

However some of their best concepts proved impossible to realise. Christo’s sketches for these abandoned projects are like visions of lost worlds.

‘All of these large works cost millions of dollars of my money – not donations, not grants. We do what we like to do, where we like to it do it. Not always when we like to do it – sometimes it takes 20 years.’

However some of their best concepts proved impossible to realise. Christo’s sketches for these abandoned projects are like visions of lost worlds. ‘Over 50 years, we arranged about 20 big projects, and we failed to get permission for 47.'

Planning and executing each enterprise was an enormous undertaking, more like building a bridge or a highway than creating a work of art. They needed to work with all sorts of people, from architects, from engineers. Jeanne-Claude’s role was just as important as her husband’s. She shared his vision, but she also had the ability to get things done.

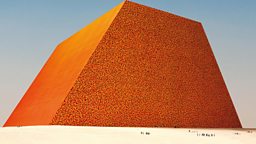

500,000 Barrels Structure - The Wall in Suez Canal

Christo was the director and she was the producer, yet for the first 33 years of their joint career, all of their artworks were credited to him alone. Since 1994, Christo has changed this practice retrospectively, and for the last 15 years of her life, Jeanne-Claude finally received the recognition she deserved. ‘The work we’re creating is bigger than our imagination,’ he says. He still talks about her in the present tense.

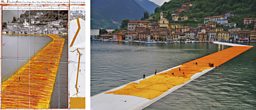

Since Jeanne-Claude’s death, Christo has carried on working, and in 2016 he realised one of his most amazing ventures, a series of floating piers in Italy, linking an island on Lake Iseo with the mainland. Personally, I think it’s the most striking artwork he’s ever made.

The Floating Piers

From June 18 to July 3, 2016, Italy’s Lake Iseo was reimagined. The Floating Piers consisted of 100,000 square meters of shimmering yellow fabric, carried by a modular dock system of 220,000 high-density polyethylene cubes floating on the surface of the water.

The Floating Piers, Lake Iseo, Italy, 2014-16

So why is he still so driven, at the grand old age of 82? "I love the reality!" he declares. "I don’t like to see a photographic image, or a film – I like to have the real thing. The real wind, the real water, the real thing!"

"It’ll be a landmark, like the Eiffel Tower"...an enduring tribute to one of the most extraordinary partnerships in modern art.

He’s now hard at work creating his largest sculpture yet - a gigantic pile of oil drums in the Arabian Desert, the so-called Empty Quarter. It’s a project he's been planning since 1979. Comprising 400,000 barrels, it’ll be even bigger than the Great Pyramid of Giza.

"It’ll be a landmark, like the Eiffel Tower." A homage to Jeanne-Claude ("She loved the desert"), it’ll be his first and last permanent structure, an enduring tribute to one of the most extraordinary partnerships in modern art.

- Three Store Fronts is at Brussels Art Fair, aka BRAFA from 27 January to 4 February 2018. Christo and Jeanne-Claude is at the Serpentine Gallery, London W2 from 20 June to 9 September 2018.

In progress: The Mastaba (Project for the United Arab Emirates)

More from BBC Arts

![]()

Picasso’s ex-factor

Who are the six women who shaped his life and work?

![]()

Quiz: Picasso or pixel?

Can you separate the AI fakes from genuine paintings by Pablo Picasso?

![]()

Frida: Fiery, fierce and passionate

The extraordinary life of Mexican artist Frida Kahlo, in her own words

![]()

Proms 2023: The best bits

From Yuja Wang to Northern Soul, handpicked stand-out moments from this year's Proms