Five of the best endings in music history

What’s the best way to finish a piece of music? And what do endings even mean – are they simply framing devices, or can they mean something more? Tom Service explores the art of the ending in a new episode of The Listening Service.

Endings are often the most exciting part of music: the place where composers and songwriters gather all their musical powers together to create the noisy, apocalyptic, tragic, existential or eternal finales of their pieces.

Let’s start with the best of the noisy composers: the ones who want the ends of their symphonies to draw listeners in with bang after crash after bang after... you get the idea.

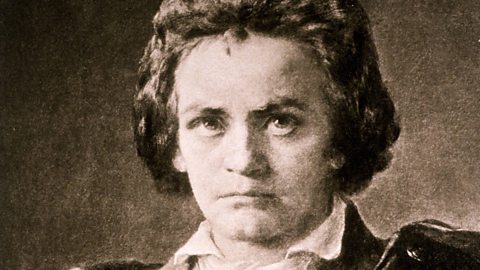

1. The ultimate noisy ending

Here’s a piece that hammers home its hard-won victory in an ever-increasing ecstasy of ending. At the end of Beethoven's Fifth Symphony, the composer ramps up the speed and energy and flings all the noise he can muster from the orchestra directly to our ear drums. It’s a pile-driver of an ending, with C major chords thrown down like lightning bolts from Thor’s hammer.

The gloriously interminable finale of Beethoven's fifth

Tom Service revels in the vertiginously exciting chords of this showstopping finale.

This is the kind of over-the-top-ending-to-end-all-endings that Beethoven made his own, and that Dudley Moore sent up so magnificently with his coda (Italian for “tail’”) of his Beethoven-inspired fantasia on Colonel Bogey.

2. The best false ending

Composers can use the endings of their pieces to pull the rug up from under our expectations as listeners. Tchaikovsky’s Sixth and last symphony, the "Pathétique", is a classic example. The third movement is like one of Beethoven’s codas on steroids, an ironically over-the-top festival of musical conclusion. Audiences often applaud at this moment, as Tchaikovsky’s music invites us to.

But it’s not the end – there’s a whole other movement still to come! And it’s a slow finale, rather than the dance of joy that had become conventional for symphonic endings in the late 19th century. In fact, Tchaikovsky’s finale is one of the most tragic and shocking descents to emptiness in all of music.

Tchaikovsky, master of the false ending

The "Pathetique" upends our preconceptions about how big pieces of music should end.

The real ending of the symphony isn’t the noise of the third movement, but the descent into the throbbing quietness, desolation and slowness of the fourth, marked "Adagio lamentoso". We feel this last movement to be even more shattering because it seems to exist outside of the frame of the rest of the piece.

3. The greatest fade into silence

Nowadays we're more likely to associate a fade at the end of a piece of music with pop rather than classical music. It's a classic technique that means we keep hearing a song long after it's over. Because when the chorus repeats, getting quieter and quieter, your ears want to follow, say, Philip Oakey down the musical rabbit hole to a place where we can all live forever, together...

Why the fade at the end of pop songs represents eternity

Tom Service analyses his favourite fade, "Together in Electric Dreams".

For a distant ancestor of the fades we hear at the end of pop songs, look no further than Mahler's Symphony No 9.

The end of Mahler’s Ninth transforms the boundary between sound and silence into an existential experience of a borderland between life and death. The music becomes so slow and so quiet in its final couple of minutes that you’re not sure when the sound of the symphony ends and the silence afterwards begins.

On its final page, the score is even marked “ersterbend” (“dying”). Yet it’s a fade not into nothingness, but into an ending that opens up a new kind of experience: an interzone between music and silence, between existence and non-existence.

4. The best apocalyptic ending

The end of Wagner’s Ring Cycle wipes the world clean of gods, dwarves and magic and gives it to the race of men. After the death of Siegfried, the hero of the 16-hour, four-opera cycle, and the immolation-suicide of the heroine, Brünnhilde, the music at the very end is simultaneously devastating and epically uplifting.

In the last few minutes of the final opera, Götterdämmerung, Wagner liquefies the four opera’s main melodies into a mythical musical soup that heightens their already overwhelming power. It’s breathtaking.

But at the very end of the Ring is a question mark rather than a full-stop. What are we going to do with this new world? What happens after this musical apocalypse?

5. The ending that never ends (well, nearly)

When it comes to music of technically finite but impossibly gigantic time-scale, the experimental band Bull of Heaven have created the most radically gigantic musical form that I know of.

310: ΩΣPx0(2^18×5^18)p*k*k*k is the longest of all of their long-form experiments, lasting – wait for it – 3.343 trillion trillion trillion trillion years. That will take us a reasonable way towards the limits of the heat-death of our universe, when the supermassive black holes at the heart of the universe’s galaxies will decay.

So what will these great galactic engines of creation and destruction sound like as they finally give up the ghost? Physicists think it’ll be a moderately loud "pop". The universe ends with a whimper, not a bang…

Discover more about musical endings in The Listening Service with Tom Service.

![]()

The Listening Service on Endings

Tom Service looks at how pieces of music end, and asks what endings mean.

![]()

How did the number 12 revolutionise music?

How Schoenberg used the Western 12-note scale to open up a new cosmos for composers and listeners to explore.

![]()

What is synaesthesia?

Tom Service examines how sounds can be experienced as colour.

![]()

Why does music move us?

What is it about music that can have such an intoxicating, physiological effect on the listener?